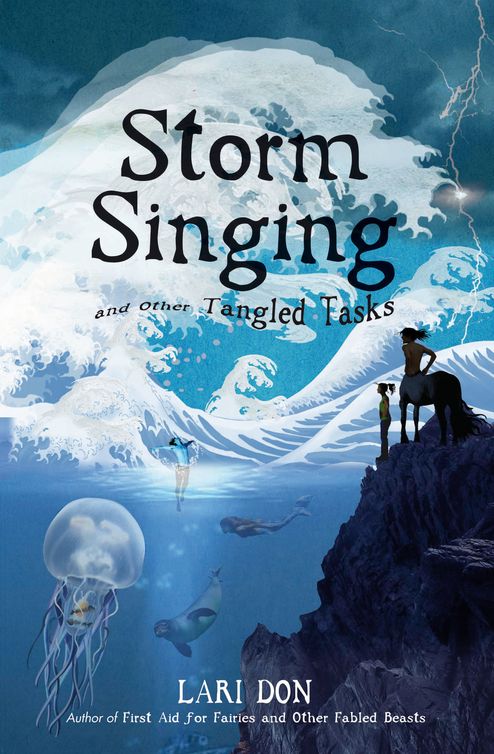

Storm Singing and other Tangled Tasks

Read Storm Singing and other Tangled Tasks Online

Authors: Lari Don

To Mirren, for her honest comments on the difficult things I make my characters do; to Gowan, for suggesting the best selkie name ever; and to Mrs Findlay’s P5 class at Inverkip Primary, for their excellent selkie research

.

Title Page

Dedication

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Chapter 26

Chapter 27

Chapter 28

Chapter 29

Chapter 30

Also by Lari Don

Copyright

Clip clop clip … splash!

“Stop giggling!”

“We’re not giggling.”

“Yes, you are! Walking on seaweed with

hooves

isn’t easy, you know.”

Helen tried not to laugh as Yann slithered over another wet rock.

“Come on, Rona,” she whispered, “let’s walk in front of him so we’re not watching him slip and slide. He gets

so

grumpy when he’s embarrassed.”

Clatter … splash!

“Don’t look back,” muttered Rona.

“Why not?”

“He’s just landed on his rear end in a rockpool!”

Helen couldn’t help looking. When she saw Yann floundering in a deep pool, she took a couple of steps back, grabbed his hand and tried to pull him out.

“Don’t be foolish, human child. You can’t lift a horse’s weight! Back off, so I don’t stand on you.”

With an inelegant lurch, he jumped out. Water ran down his boy’s back and off his chestnut horse’s body. He shook his long auburn hair and flicked a tiny crab off his withers.

“Stop staring! Just leave me alone to go at my own pace over this horrible beach.”

Yann moved his front left hoof gingerly forward, aiming for a small flat patch of sand, but his back hooves slipped, and he splashed into a shallower pool.

“For goodness sake!” Rona marched off, her smooth hair bouncing against the furry rucksack on her shoulders, her ankle-length dress trailing in the rockpools.

Helen watched Rona walking away, then glanced at Yann, who might break a leg if he went too fast. There weren’t any splints long enough for a horse’s leg in the first aid kit hanging from Helen’s right shoulder. Should she chase after Rona, or follow behind at Yann’s pace?

Yann yelled suddenly, “Rona! Come back!”

“No! I can’t be late!”

“Come and look at this!”

“Look at what, the seaweed in your tail?”

“Rona Grey, I’m serious. Come here!”

Rona turned back, glancing up at the sun in the same irritated way Helen’s mum checked her watch when she had to get Helen to school, Nicola to nursery and already had animals queuing outside her vet’s surgery.

“What?” Rona demanded.

“Look at that sand …” The centaur pointed between his front hooves.

Both girls stared at a clear patch of sand.

“There’s nothing there!” they said at the same time.

“Precisely. There’s nothing there. It’s completely smooth. Something has been rubbed out.”

Helen peered closer. The stretch of sand

was

utterly smooth. She looked at other patches of sand between the rocks. They were marked with bird footprints and the soft lines of the last tide.

Rona knelt down and sniffed. “You’re right. No

windblow

n

grains. No salty crust. Someone has brushed this.”

“Someone has covered their traces,” insisted Yann. “Someone who doesn’t want anyone to know they’ve been here.”

“Who?” asked Rona, her irritation turning to worry.

Yann shrugged. “Someone spying on the Storm Singer competition?”

“But it’s a public event. Any sea being or fabled beast is welcome to watch. And humans don’t know about it.”

“I know about it,” said Helen.

“Only because I invited you.”

“We can’t tell who it is unless we track them,” said Yann. “We can’t tell what they want unless we ask them.” He cracked his knuckles and grinned.

Helen sighed, and Rona shook her head.

“It’s a peaceful competition, Yann, not a battle,” said Rona. “I’m sure someone brushed the sand for a perfectly sensible reason.”

“I’ll investigate,” announced Yann.

“

You?

” snorted Rona. “

You

are struggling to walk in a straight line on this beach. I suppose I’d better go.” She looked at the sun again.

“You can’t go,” said Yann. “You only get one chance to enter the Storm Singer competition, Rona, and if you win that, it’s your only chance to become Sea Herald. You can’t be late. I’ll go.”

“No,” said Helen. “I’ll go. You two get to the competition at your own speeds, and I’ll check out this possible spy.”

“If you find a spy, Helen, what will you do?” demanded Yann. “If you find a kraken or blue man, a

sea kelpie or sea serpent, a nuckelavee or giant eel, what will you do?”

Helen frowned at Yann’s scary list, then shrugged. “See if they need a plaster? Play them a solo on my fiddle?” She patted the violin case on her back.

“Don’t joke, human girl. The edge where sea and land meet may be a holiday destination to you, but like any joining of two worlds, it draws evil beings from both.”

Helen grinned. “I’ve dealt with a power-hungry minotaur and a child-stealing Faery Queen in the last year. I can sneak up on a seaside spy.”

Rona wailed, “But if

you

go, Helen, you won’t hear me sing!”

“Yes, I will. Your volume and confidence have improved so much in the last two days, I’d hear you even if I was still in Taltomie.”

Rona blushed. “Do you think so? If I’m louder and more confident, it’s because of your coaching. You’re much better at performing than me.”

“You write better music, so it evens out. Now get going, and I’ll track down your mystery guest. I’ll probably be in the audience in time for your songs, and if not, just project loudly enough to reach me wherever I am. Good luck!”

They hugged, and Rona smiled. “I’ll get to Geodha Oran faster without you two anyway.”

She ran down to the sea’s edge, pulled her furry rucksack off, flapped it open, and swung the sealskin cloak over her shoulders. She shimmered in the sunlight reflecting off the sea, crouched on the rocks, then bounced into the water.

A seal.

She waved a fin, and swam off.

Helen turned to Yann. “You carry on along the seaweed, while I go on this wild-goose chase.”

“If it’s something as small as a wild goose that’s been covering its tracks, I’ll be delighted. Anyway, I’m coming with you.”

“You’re as wobbly as a newborn foal on these rocks. What use will you be?”

“The creature isn’t on these rocks. The patches of cleared sand lead up the beach, towards that cliff. Even if it isn’t doing anything sinister, it seems to be taking an inland route to the venue. So I’ll get there faster and safer by following it.”

Once Yann had struggled to the base of the cliff, he pointed up the steep rock wall. “A path, with more brush marks. Let’s climb up.”

Now it was Helen’s turn to feel insecure. Yann trotted up the gritty narrow path like a goat, while Helen concentrated on every step.

When they got near the top, Helen whispered, “I’ll peek over, I’m smaller and quieter than you.”

She edged past Yann and saw an expanse of pale saltblown grass, with grey rocks scattered along the cliff edge as if they’d been tossed there by storms. “It’s clear. Nothing here.”

Yann stepped up, and checked the landscape carefully, just in case Helen had missed a sea monster right in front of her. He nodded. “It’s clear, and I can’t see any tracks on this grass. Let’s go towards Geodha Oran. If this creature is watching the contest, we’ll spot it on the way.”

As they followed the jutting and jagged coastline,

Helen asked, “What’s a Sea Herald?”

“Pardon?”

“I thought Rona was competing in the selkies’ Storm Singer competition, but you said this was her only chance to become a Sea Herald. What did you mean?”

“Hasn’t she told you, all those mornings you’ve spent screeching on the beach?”

Helen shook her head, and Yann smiled down at her, like he always did when he explained something Helen didn’t know.

“This afternoon’s competition, ignorant human child, is just for selkies competing to become a Storm Singer, the highest level of sea singer. Today’s victor then enters a contest between selkies and other sea tribes, to become Sea Herald. Hardly any Storm Singers get the chance to be Sea Herald, because these contests are held very rarely, so Rona is under a lot of pressure to win.

“Her mum and two cousins are Storm Singers. Her great-grandmother was a Sea Herald. Rona has a family reputation to uphold. Maybe that’s why she didn’t tell you, in case it made you both nervous.”

Helen frowned. “She did say it was a family tradition to win the Storm Singer competition. She’s wearing the dress her mum wore when she won. But she didn’t say that if she wins she’ll have to enter another competition! I don’t know if I can coach her through more songs. She gets so

anxious

!”

“You won’t have to. The Sea Herald contest isn’t a performance, it’s a race and a quest. If she becomes a Storm Singer with your help, she’ll need my help to become Sea Herald.”

“Rona? In a race and a quest? You’re kidding!”

Helen wished she hadn’t given Rona so much advice on performing. Perhaps Rona would be happier if she didn’t win this competition, then she wouldn’t have to endure another one.

But Rona’s greatest pleasure was to write and sing songs, and the winning Storm Singer was invited to sing at lots of fabled beast gatherings.

Then Helen heard distant voices and faint laughter.

“We’re nearly there,” said Yann. “Let’s find a place we can watch as well as listen.”

“What about the …?”

Suddenly they both saw it.

A rock, on the cliff edge.

A pool of shadow behind the rock.

A shape, shifting, in the shadow.

Helen and Yann stopped.

The figure moved round the rock, peered down at the crowd below, and the bright afternoon sunlight touched its head.

Helen and Yann gasped.

“What

is

that?” Helen whispered, as they crouched behind a pile of stones.

“I have no idea,” said Yann.

Before the figure had slithered back into the shadow, they’d seen it clearly in the sunlight. But instead of shining onto the creature, the sunlight had shone through it. Helen had seen a crouched body, clear and gooey, with purple lines and pink circles inside transparent flesh, and a huge oval head.

“You don’t know what it is?” she asked.

“No.”

“I thought centaurs knew

everything

!”

He scowled. “I know all the fabled beasts of the land, but we don’t actually study sea beings …”

“So you don’t know any more about sea creatures than I do? You’re just as ignorant as I am!”

“Not

quite

as ignorant.” His scowl softened into a grin. “Usually I know at least one more thing than you do, which keeps me far enough ahead that you think I know everything.”

Helen shook her head. “Rona will know what it is, even if you don’t. We can describe it to her later. All we need to know now is whether it’s dangerous.”

“It doesn’t look very hard and scary,” muttered Yann. “It looks like someone sneezed it.”

“What’s it doing here?”

“Maybe it’s a fan of seal singing.” Yann didn’t sound convinced.

Helen peered over the stones. “If we can find a big enough rock on the cliff edge, we’ll be able to watch the competition and keep an eye on the spy.”

Fifteen minutes later, they were hiding on the far side of a lumpy rock on the very edge of the cliff. Helen knelt down to look at the venue, Geodha Oran, a high narrow inlet slicing inland through the cliffs.

On the lower ledges she saw older selkies in their smooth blotched grey seal form, and higher up she saw young selkies in their human form, with silky tunics and straight hair, nibbling fishsticks and giggling.

She saw Rona, perched in human form on a ledge with five other competitors at the landward end of the inlet, where the rock walls would funnel their voices out to sea.

“Don’t wave at her,” ordered Yann. “If she waves back, the snot monster will know we’re here.” He glanced round their rock, towards the spy’s hiding place, which was closer to the singers’ end of the inlet. “It’s not moved. I’m a little concerned that it covered its traces, but I don’t see what harm it can do from up here.”

“Could it knock the rock down onto the competitors?”

“I’ve considered that. Look at the rubble round the rock’s base. It couldn’t be rolled, it would have to be lifted and thrown, and I doubt that lump of mucus has strong enough arms to lift a rock that size.”

So they sat, Yann with his legs folded elegantly under him, Helen with her feet dangling over the cliff, taking turns to keek round at the spy and look at the assembly below.

Then Helen noticed two ledges which weren’t filled with selkies. One ledge glittered with silver scales and pale wavy hair; the other ledge was a shadowy blue.

“I thought this was a selkie competition. Who are they? Or don’t you know?”

“Of course I know! They’re observers from the other clans entering the Sea Herald contest.”

Helen pointed to the silvery ledge. “Are those …?”

“Yes. Mermaids.”

“And the blue people?”

“Blue men of the Minch. They …”

But a large selkie, with a deep scar on his face and neck, called for quiet. The Storm Singer competition had begun.

The six competitors lined up on the singing ledge, and the scarred host announced the running order. Rona’s name was at the end.

Helen settled back to enjoy the music, and to judge for herself if anyone sang as well as Rona. She listened to the first selkie sing a fishermen’s lament in human form, followed by a sea shanty as a seal.

Each competitor would sing three songs: a traditional song, a song they’d composed themselves and an improvised song. The rules also stated that the selkies had to sing at least one song in their seal form, and at least one in their human form.

Helen wasn’t impressed by the first seal, Rona’s cousin Rory from John O’Groats, sixty miles east along

the coast. She hoped to hear melodies which would inspire her to create new fiddle tunes, but his songs were repetitive, and his voice, singing the long vowel sounds selkies love, was reedy.

Helen glanced round at the creature. It was still hidden in the shadow.

The next competitor, a tall selkie from Shetland, sang her first song in human form, so Helen could follow the words. “Another one obsessed with fishermen.”

Yann sighed. “These selkie songs are all the same.”

“Rona’s songs are more original.”

Rona respected the old songs, but the ones she wrote herself were influenced by her adventures with her friends, and the music she heard on sleepovers at Helen’s.

“If she’s too modern,” said Yann, “the older selkies won’t vote for her.”

Helen closed her eyes, enjoying the original rhythm the Shetland selkie had written for her own song, even if it was yet another ballad about a selkie falling in love with the fisherman who’d stolen her skin.

Yann muttered, “Why don’t they just whack the human on the head with an oar and grab the skin back? It’s like they

want

to be captured and live their life trapped on land.”

When the third competitor, from the Isle of Man, started to sing in Selkie, Helen couldn’t understand the lyrics, so she leant back to check on the spy. It was almost impossible to see anything in the black shadow, surrounded by the bright sunlight bouncing off the yellow grass. But the creature still seemed to be squatting behind the rock, listening to rather than watching the competition.

She shrugged and turned back to listen to the Manx selkie singing her own composition, a spooky song about sailors trapped in sinking ships. Then the host announced the subject for her improvisation. The selkie trilled a scale to get herself warmed up, and began.

Helen shook her head. “She’s copying a Western Isles lullaby. It doesn’t really work for a song about eels lurking in caves.”

“One less for Rona to worry about,” said Yann.

The next competitor was from Rona’s own tiny selkie colony. Helen sat up straighter. “That’s Roxburgh. I’ve heard him practise with his dad. He’s really good. He could be absolutely brilliant, if his dad would let him do it his own way, instead of bossing him about all the time.”

Yann frowned as Roxburgh’s voice ripped up the cliff towards them. “Is he better than Rona?”

“Not

better

than Rona, but he sings the traditional songs with a huge amount of emotion. Listen.”

“It’s like he’s torturing the words,” said Yann.

“It’s crowd pleasing. He’s singing it the way they all wish they could.”

Roxburgh flung himself into the chorus, sounding as if he was about to burst into tears, or scream in murderous anger, with every single note. Helen sighed, and turned round to check on the creature.

And the sun went behind a cloud.

As the sunlight dimmed, the shadow vanished.

Helen could see a transparent figure. Its purple skeleton. Its pink innards. Its see-through stomach, filled with two partially digested fish.

“Yuck! Look at this.”

Yann stretched round, but the sun reappeared and dazzled them both.

As the sharp black shade hid the spy again, Helen saw one more thing.

A bag. A thin fishskin bag, like Rona’s mum carried. On the ground at the spy’s feet. Wriggling.

“What did you see?” asked Yann.

“It’s like a jellyfish squished into a gingerbread-man shape, and it has a bag, filled with something moving, something

alive

.”

Helen heard the first few notes of Roxburgh’s own composition, a battle hymn about his selkie king ancestors, as she whispered urgently to Yann, “What do we do?”

“We attack it before it attacks the selkies!”

“If it’s going to attack them, why didn’t it attack at the start? And what’s in the bag?”

“Weapons, perhaps, or something it’s planning to tip on the selkies’ heads. We can’t wait until it attacks to find out.” Yann pushed up from his kneeling front legs. “I’ll grab the bag.”

“Don’t be silly. You can’t creep up on it with hooves. I’ll go.”

“Don’t be daft. You’re not …”

Helen didn’t have time for a repeat of the

eeny-meeny

- miny-mo argument on the beach, and Yann couldn’t shout after her without alerting the spy, so she ignored him and slid round the rock on her tummy.

She crawled through the dry grass. If the creature looked round, her red fleece and blue jeans would be easy to see, but it had its back to her and the gentle

rustling of her approach was covered by Roxburgh’s loud voice.

When she was halfway to the spy’s rock, she saw a pale arm move inside the shadow, reaching for the writhing grey bag.

The creature was about to launch its attack!