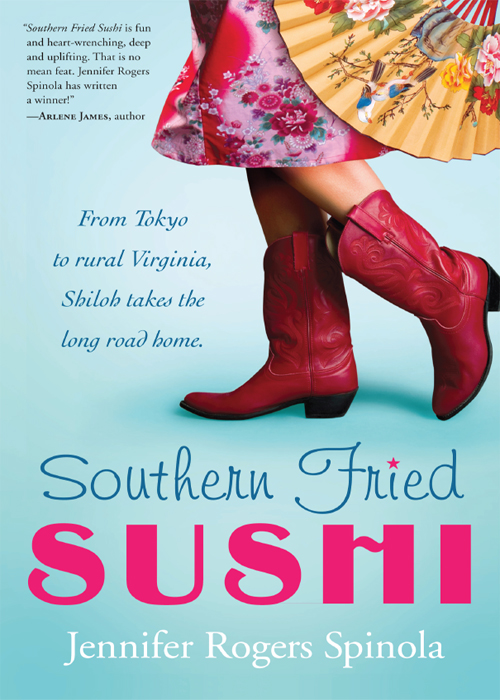

Southern Fried Sushi

Read Southern Fried Sushi Online

Authors: Jennifer Rogers Spinola

© 2011 by Jennifer Rogers Spinola

Print ISBN 978-1-61626-364-5

eBook Editions:

Adobe Digital Edition (.epub) 978-1-60742-558-8

Kindle and mobipocket Edition (.prc) 978-1-60742-559-5

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without written permission of the publisher.

Scripture taken from the Holy Bible, New International Version

®

. Niv

®

. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984, 2011 by Biblica, Inc.™ Used by permission. All rights reserved worldwide.

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either products of the author’s imagination or used fictitiously. Any similarity to actual people, organizations, and/or events is purely coincidental.

For more information about Jennifer Rogers Spinola, please access the author’s website at the following Internet address:

www.jenniferrogersspinola.com

Cover design: Faceout Studio,

www.faceoutstudio.com

Published by Barbour Publishing, Inc., P.O. Box 719, Uhrichsville, OH 44683,

www.barbourbooks.com

and distribute inspirational products offering exceptional value and biblical encouragement to the masses.

Printed in the United States of America.

To my mother, Doris Lambert Rogers, whose only resemblance to Ellen Jacobs was steadfast faith until her last petal fell. Thank you for singing so beautifully. 1952-1996

People often ask me how a writer gets published, and I have to be frank: I have no idea. Why me? Why now? Why this book? I can’t answer the whys, but I know one thing: apart from God’s extravagance and helping hands along the way, I’d never be seeing my work in print. Although my name appears on the cover, it’s not just me who’s written a book.

It’s Roger Bruner and his wife, Kathleen, whose first exuberance over my manuscript put hope in my heart, and whose encouragement and editing ideas kept me going along the way. It’s my deputy cousin Lessa Goens, whose quick-fire texts when I desperately needed a plot twist or rescue or piece of legal info kept me from chucking everything out the window.

I thank teachers all the way back to my third-grade teacher, Sandra Thompson, who took me seriously enough to read over my handwritten manuscript (and not laugh!), to college professors Dr. Gayle Price, Dr. June Hobbs, Bob Carey, and Jennifer Carlile who pushed me forward and encouraged my writing for life. At my first job it was Anita Bowden and Mary Jane Welch who refined my verbs and helped me find my voice; Mark Kelly and Erich Bridges showed me how to change the world through words, one article at a time. You are all my heroes.

I’d be lost without my crit partners Jennifer Fromke, Shelly Dippel, Christy Truitt, and Karen Schravemade, and even more lost without the love and hands-on help of my handsome Brazilian husband, Athos Spinola, and the cooperation of my two-year-old son Ethan. I love you both more than anything.

Mom, Dad, and Winter, I remember your encouragement through those long years of handwritten stories and hold them close to my heart. Thanks also to Aunt Lois, Aunt Ruth, and Grandma for reading so many of those little stapled-together books and always making me think they were wonderful.

To my editor, Rebecca Germany, thanks for taking a chance on an unfamiliar face. April Frazier and Linda Hang and Laura Young at Barbour, thanks so much for your hard work.

To Jesus Christ, my Savior forever, I owe you everything. You are my life. Why me? I will never understand.

To those who have stood by my side: there are no solitary journeys. This is all your work. Thank you from the bottom of my heart.

U

h-oh.” Kyoko peeked over the cubicle at me with suspicious black-lined eyes. “They got your work address.”

I stared at the envelope Yoshie-san dropped on my desk. Citibank Corp, it read. Not good.

“Mou ichimai

,“ said Yoshie-san slowly, sifting through the mail stack. “One more. For Shiloh Jacobs.” At least he meant to say “Shiloh.” His thick Japanese accent rendered it so incomprehensible, it might have been “Spaghetti.”

“Busted,” whispered Kyoko insolently.

I waved her away with a scowl. “Mind your own business.”

“Sumimasen. Mou nimai

. Sorry. Two more.” Yoshie-san’s ink-stained fingers stopped on two more envelopes. “American Express. Daimaru.”

I snatched them out of his hand and shoved them under my notebook. “You don’t have to read my mail out loud!”

“You have a Daimaru card?” Kyoko stared. “From that big department store?”

I ignored her. “I’m busy. My big story on the Diet’s due.”

“I want a Daimaru card. How’d you get it?”

“Go to Daimaru and find out yourself.”

“You know, it’s pretty much impossible for foreigners to get

credit cards here. What’d you do?”

I launched a paper ball over the cubicle wall and socked her squarely on her sleek bob, tinted with that mod dark purple-red tone we saw everywhere. In fact, I don’t remember seeing anyone in Japan with black hair except Yoshie-san, the office helper. I saw chestnut and auburn and bleached blond in abundance, but no black. I should make a list.

Black hair? Yoshie-san. Mod purple-red? Kyoko. My next-door neighbor, Fujino-san

. I added some more ticks. I should do a study on this for my master’s. “Modern Japanese and Hair Color: A Study in Transitions.”

“Ouch. What’s your problem?” Kyoko rubbed her head. She spoke with perfect coastal English that betrayed her California roots. If I didn’t look up, I’d think I sat across from a surfer.

The cursor blinked on my screen, and I typed a few more lines about the Japanese legislature, otherwise known as the Diet. When previous Prime Minister Koizumi’s son starred in an ad for diet soda, I’d begged to write the article. The puns were too tempting. But thankfully somebody axed the idea before it ever made it to editor Dave Driscoll.

Somehow I’d become the reporter Associated Press tapped for political stories. Kyoko dabbled in legal articles.

“Wanna go to lunch?” Kyoko could change subjects in the blink of an eye.

“Meeting Carlos. In Shibuya.” The corners of my mouth turned up.

Tap, tap, tap

from Kyoko’s side. “Wanna join us? He’s bringing along his new roommate. Wants me to check her out and make sure she’s … you know. Normal. Not psycho or anything.”

“Her?” The tapping stopped. “You’re kidding, right?”

“I said the same thing. But he told me not to worry. Just business, and he’s not attracted to her and whatnot.”

“They all say that.”

“He’s engaged. To me.” I waved my ring at her.

“Doesn’t mean a thing.”

I glared at her again. “I trust Carlos. He’s never lied to me.”

No response. Just those black, overplucked eyebrows. She thinks I’m a moron.

“Do you want to come or not?”

“I’d better. Moral support. ‘Cause believe me, you’re gonna need it.”

“Whatever.”

“Five more minutes. Gotta get this to editing ASAP.”

I added a few more lines, saved, and turned off the screen. The end of this month made two years working for the Associated Press bureau in Tokyo as a news reporter—a heady jump from college papers and my aspirations of the

New York Times

for as long as I could remember.

Not that I hadn’t worked for it though. I’d grown up in Brooklyn, read every page of the paper since age eight, and studied my tail off at Cornell—double majoring in Japanese and journalism. Studied a year abroad at Kyoto University, number two in the country, and homestayed in Nara. Interned at the

Rochester Democrat

and

New York Post

and worked six months at my beloved

Times

. And suddenly I found myself in Shiodome, Tokyo, in a brand-new office, halfway through my online master’s program in journalism and ethics. With awards lining up behind my name.

Kyoko slung her black skull-printed purse over her shoulder and played with the mouse while I gathered my purse and keys.

The corners of the envelopes stared at me accusingly, and I quietly slid my notebook back.

Shiloh P. Jacobs

, they read in stern, accusing fonts. No mistake. Not only was there no possibility of another Shiloh Jacobs in the entire country, but the amazing Japanese postal system once delivered my friend’s letter from New York when the address smudged. They read the names in the letter, guessed the recipient from the context, and forwarded the letter—to mycorrect apartment no less. Back in Brooklyn I still got mail for Mr. Pham, who’d moved back to Vietnam in 1987.

I was still staring at the envelopes when Kyoko scared me by appearing over my shoulder.

“Uh-huh. As I suspected.”

I slapped my notebook down over the envelopes and pushed her with both arms. “Out! Now!”

“How much did your last trip cost?” We walked through rows of cubicles with reporters typing furiously and piles of paper, sprawling books, and boxes stacked everywhere. Reporters never close books or throw paper away; they just stow them somewhere for future use.