Soulstealers: The Chinese Sorcery Scare of 1768 (18 page)

Read Soulstealers: The Chinese Sorcery Scare of 1768 Online

Authors: Philip A. Kuhn

The use of charms and amulets to "ward off evil" (pi-hsieh) was

universal. Much of this protective activity was directed at vengeful

ghosts (kuei), which proceeded from the yang aspect of the soul: spirits

of the dead that had not been ritually cared for. In the same manner,

there were remedies against magical evil inflicted by sorcery. Because

the masons of Te-ch'ing were objects of a common popular suspicion

of builders, let me illustrate charm remedies by referring to builders'

hexes. According to the missionary folklorist N. B. Dennys, writing

from Canton: "There is a well-known legend amongst the Cantonese

of a builder having a grudge against a woman whose kitchen he was

called upon to repair . . . The repairs were duly completed, but

somehow or other the woman could never visit the kitchen without

feeling ill. Convinced that witchcraft was at the bottom of it, she had

the wall pulled down, and sure enough there was discovered in a

hollow left for the purpose `a clay figure in a posture of sickness.' "15

Why did people associate builders with sorcery? The Chinese

believe that the ritual condition of buildings influences the worldly

fortunes of their inhabitants. It is only natural, then, that builders

had special responsibilities for practicing "good" magic when putting

up structures. The timing, layout, and ritual order of construction

were deemed essential to keeping evil influences out of the completed

building. Of course, anyone capable of "good" magic is also capable

of "bad." A carpentry manual popular in Ch'ing times, the Lu-panching, accordingly contains not only rules for proper ritual construction but also baleful charms for builders to hide atop rafters or under

floors. Quite evenhandedly, it also includes charms to be used against

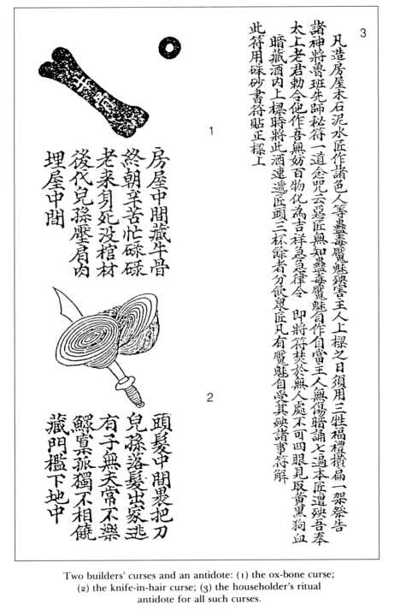

such evil builders."' Here are some examples of carpenters' baleful

magic:

A drawing of a broken tile inscribed with "Ice melts" [the rest of

the expression is "tiles scatter"-implying collapse or dissolution].

Appended is a charm: "A piece of broken tile, a jagged edge, hidden

in joint of roof-beam, husband die and wife remarry, sons move away, servants flee, none will care for the estate." (To be hidden in a joint of

the main roof-beam.)

A drawing of an ox-bone. The charm: "In center of room hide ox-bone,

life-long toil, life's end death but no coffin, sons and grandsons will

shoulder heavy burdens." (Bury under center of' room.)

A drawing of a knife among coils of hair. The charm: "A sword worn

in the hair. Sons and grandsons will leave and become monks. Having

sons who found no families, perpetual misery. Widow and widower,

orphaned and childless, do not forgive each other." (Bury under

threshold.)

But the reader is also offered powerful magic for defending the

household against builder-sorcerers:

When building a house, various kinds of carpenters, masons, and plasterers will plot to poison, curse, and harm the owner. On the day when

the roof-beam is raised, offer a sacrifice of the three types of animal,

laid out on a horizontal trestle, to all the gods. 't'hen recite the following

secret charm of Master Lu fan [patron saint of carpenters]: "Evil

artisans, do you not know that poisons and curses will rebound upon

yourselves, and bring no harm to the owner "Then recite seven times:

"Let the artisan [responsible for the sorcery] meet misfortune." [Then

say,] "I have received the proclamation of the Supreme Ruler [the jade

Emperor] ordering that I shall suffer no harm from others, and that

all will redound to my good fortune: an urgent decree." Burn copy of

charm in private place, especially where no pregnant woman can see

you. Mix ashes with blood of black and yellow dog, then dissolve in

wine. On day main roof-beam is raised, serve to builders (three cups to

boss). He who is plotting sorcery will himself receive the harm. (Copy

in vermilion ink and paste atop roofbeam.)

Such visions of offensive and defensive magic display the anxieties

that affected most common people all the time: premature death,

ritually faulty burial, loss of children, lack of proper ritual care after

death. Although these anxieties center on building-sorcery, they

really reflect a view of the world in which human fortunes are generally vulnerable to supernatural vandalism. In the unending confrontation between gods (shen) and ghosts (kuei), human life needs

the protection of whatever arts (fa or shu) can be mobilized, either

from ritual specialists or from laymen's lore."

Suspicions of the Clergy

In the campaign against soulstealing, Buddhist monks and the occasional "Taoist priest were the prime suspects from the very beginning. Why was Hungli so quick to believe in these monkish master-sorcerers

and to turn the energies of the state against them? And why was the

common man so quick to pounce on the nearest monk whenever

fears of sorcery crossed his mind?

Official Treatment of the Clergy

The commoner's daily battle against evil spirits was mirrored, at the

very top of society, by the concerns of the imperial state. Even as it

prohibited sorcery, the state was itself constantly dealing with the

spirit world. On every level of officialdom, from the imperial palace

to the dustiest county yamen, agents of the state were intermediaries

between man and spirits. Their role marks them, in a sense, as priests:

communicating with the gods on behalf of mankind to ensure the

proper ordering of worldly events, primarily good conditions for

agriculture and peace for the realm. At the top, the emperor himself

presided over solemn annual sacrifices to Heaven and Earth. At the

bottom, the county magistrate (a little emperor in his own realm)

regarded the City God (ch'eng-huang, a magistrate of the spirit world),

as an essential coadjutor in governing.

Although the common man was barred from celebrating the imperial and bureaucratic cults, he did share some of their theology.

Formal worship of Heaven was a monopoly of the monarch, but the

common people were already inclined to believe in Heaven's power

in human affairs. Because everyone's fate was governed by heavenly

forces (the succession of the "five actions," wu-Iasing, and the interplay

of the cosmological powers of yin and yang), people easily accepted

the connection of imperial Heaven-worship with human felicity. And

because the fate of the individual soul after death was thought to

depend on a judgment of merit by the City God, commoners considered that worship of that deity by local officials was performed on

behalf of the community as a whole."' If the state were to sustain

these popular beliefs in its own spiritual role, it had to watch carefully

for potential competitors.

The state's inclusive claim to be the rightful manager of man's

relations with spirits led to elaborate procedures for regulating the

organized Buddhist and Taoist clergy. There was, of course, something a bit absurd about the state's rules regarding the clergy. The

majority of ritual specialists were not "enrolled," in any formal sense,

under organizations that could be held to account for their activities. The priests of the popular religion, who headed an eclectic, deeply

rooted system of community practices, were not even full-time clerics,

in the sense that we might expect from a Western context. For the

state to forbid ambiguous status, insist on clear-cut demonstration of

master-disciple relationships, and require registration of all religious

practioners were ludicrous presumptions in view of the actual practice of Chinese religion. Marginality (as the state would define it) was

built into the social status of most ritual specialists. To fasten upon

them regulations such as those I shall summarize here would have

erased popular religion itself, which of course the state (in those days)

would have found an impossible task. This simple fact gives discussions of "state control of religion" an unreal and fantastic aspect.3°

Nevertheless, the attempt was made. We have to regard it as an

indication of state attitudes, rather than as a "system" that actually

functioned in anything like the way it was intended to. According to

the rules, all temples and monasteries, along with their clergy, had

to be registered and licensed. It was illegal to build a temple without

formal approval of' the Board of Rites. In the same spirit, the state

had for centuries required Buddhist monks and Taoist priests to

obtain certificates of ordination (tu-tieh).41) Why was the late imperial

state so concerned to register and control ritual specialists? When the

ninth-century T'ang empire confiscated vast monastic properties and

returned tens of thousands of monks to lay life, the reason was partly

economic: a man's withdrawal to a monastery removed him from the

liabilities of taxes and labor service and so deprived the state of

revenue. Yet this purpose was irrelevant in the late empires, when

labor-service obligations had been commuted to money payments and

assessed along with the land tax, in effect replacing corvee by paid

labor. A review of the Ch'ing efforts to control the clergy suggests

other purposes.

Although licensing and registration of monks and priests had been

practiced by the preceding Ming Dynasty, it was not until 1674 that

the Manchu throne issued its first general instructions on state governance of the clergy. In Peking, offices were established for the

supervision of Buddhists and Taoists, each to be staffed by sixteen

monks or priests, members apparently to be initially selected by the

Board of Rites, but to be replaced by co-optation from among the

capital clergy. The members of these supervisory bodies were to be

reported to the Board of Civil Office (h-pu).`" A parallel system was

decreed for the provinces: offices staffed by selected monks and priests were established in prefectures, departments, and counties.42

They reported up the regular chain of bureaucratic command.

The supervisory offices were to regulate the deportment of monks,

priests, and nuns, to ensure that they honored their vows by proper

discipline. Beyond this, however, was the all-important licensing.

Here the point was not so much to maintain the purity of the clergy

themselves as to insure against unreliable laymen representing themselves as clerics. The Throne feared that "riffraff and ruffians" would

falsely assume clerical habit and claim to be invoking the spirits of

(religious) patriarchs (tsu-ship) through divination. Such powers to

communicate with spirits and foretell the future would generate

"heterodox doctrines" and "wild talk" that could attract ignorant

people to become their followers and form illegal sects. By heterodox

doctrines and wild talk, the Throne meant not only pretensions to

magical powers by sect leaders but also prognostications about the

fate of the existing political order. Imperial decrees on this subject

show special sensitivity to religious activities in Peking, the seat of

dynastic power. Temples and monasteries in the capital were forbidden to "establish sects and hold assemblies where men and women

mix together" (a hallmark of popular religion-and further evidence,

to the imperial mind, of moral degeneracy). Nor were they allowed

to "erect platforms to perform operas and collect money, sacrifice to

the gods, or carry them in procession." "

Emperor Hungli himself was particularly irritated by ambiguity of

status, which led him to try to extend the regulations on the organized

clergy (those in major monasteries or temples) to the vast majority of

ritual specialists in lay communities. His first major pronouncement

on the clergy concerned persons who might be called secular clergyactually the majority of ritual specialists: those who lived permanently

outside monasteries and temples, owned property, and even married.

Such men played it vital role in communities by serving in funerals

and exorcisms, and otherwise filling people's needs for ritual services.

They were subject neither to monastic discipline nor to state control.

After denouncing the decayed state of clerical morals and learning,

Hungli ordered that these secular practitioners be forced either to

live in monasteries or temples, or else return to lay life. Their property, save for a bare subsistence allowance, was to be confiscated and

given to the poor. When it appeared that the decree was causing

panic among clergy in general and provoking disorder in the provinces, Hungli protested that he had never meant to harm those who hewed to clerical discipline. The problem, rather, was public order.

These secular personnel "steal the name of clergy but lack their

discipline. They even engage in depraved and illicit activities. They

are hard to investigate and control." The reason he was requiring

that they obtain ordination certificates "was so that riffraff would not

be able to hide in their midst and disgrace Buddhism and Taoism."

The newly enthroned monarch was evidently surprised by the reaction to his harsh measures. He now recoiled from the confiscation

order: "Finally, how can Our Dynasty's relief of the poor depend on

the seizure of such petty properties?" The decree was rescinded. But,

burdening the monarch's mind, there remained the irksome existence of a mass of ritual specialists who were not under any kind of

state supervision.44