Soulstealers: The Chinese Sorcery Scare of 1768 (13 page)

Read Soulstealers: The Chinese Sorcery Scare of 1768 Online

Authors: Philip A. Kuhn

Late ,July, 1768: The worst of the summer's heat was already upon

Peking, and at the Forbidden City preparations were under way for

the annual move to the summer capital at Ch'eng-te. There, in the

hills and forests of the old Manchu homeland beyond the Great Wall,

was a cunningly designed park in the style and spirit of Kiangnan-

the lower Yangtze region where Hungli, like his grandfather before

him, delighted to tour. On 1,300 acres lay palaces of sumptuous

rusticity and pleasure pavilions in the southern style, set amid serene

lakes fringed with willows and artfully contoured to conceal artifice.

This little touch of Kiangnan in Manchuria had been created in 1702

by the K'ang-hsi emperor, Hungli's grandfather, and was greatly

expanded by Hungli himself.

Spending the hot months there was more than a relief from the

unpleasant Peking summer. By coming to Ch'eng-te, the monarch

could lead his Manchu elite back to their old haunts, summon them

to the saddle, and marshal them on grand hunts and maneuvers in

the old rugged style. Here hardihood could for a season replace

refinement, and the dust of settled life be shaken, however briefly,

from the feet of the conquerors. High politics were served, too: here,

at the gateway to the forests and steppes, Inner Asian lords could be

entertained and their dependency upon the emperor reaffirmed.

Here the Inner Asian faith of Lamaist Buddhism, key to controlling

Mongolia and "Tibet, was lavishly patronized by Hungli. To appeal to

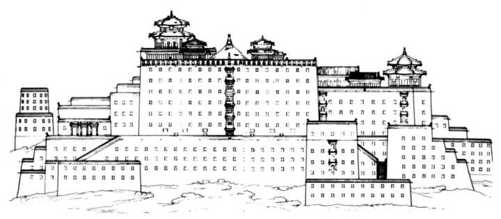

Lamaists, he constructed magnificent temples in the Tibetan style. At the time of our story, Hungli had already begun to construct the

gigantic imitation of Lhasa's Potala, to serve the devotional needs of

Inner Asian lords at the celebration of the imperial sixtieth birthday

two years later. This curious summer capital, an amalgam of Manchu

machismo, Kiangnan kitsch, and Inner Asian diplomacy, was a mere

130 miles from Peking; two days sufficed for a courier to bring a

report from the committee of grand councillors left behind in Peking

and return with an imperial reply. The business of the empire went

on uninterrupted.

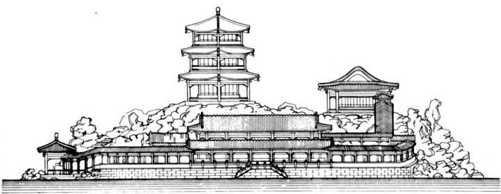

The Chin-shan temple complex, approximately 178 feet in length from left

to right, at Ch'eng-te. Built in the Kiangnan style by Hungli's grandfather

in imitation of a temple in Chinkiang, Kiangsu Province, that he often

visited on his southern tours.

The Tibetan-style potala at Ch'eng-te, begun in 1767 and completed in

1771. Left to right, approximately 477 feet.

Evil from the South

Just before the court set forth for these summer pursuits, the

emperor received some secret intelligence. How he found out about

the situation in Shantung is carefully hidden behind the vague beginning of the July 25 court letter in which he first broached the case.

The drafting of the letter was entrusted to the three senior grand

councillors, Fuheng, Yenjisan, and Liu T'ung-hsun, and addressed

to the provincial officials of Chekiang, Kiangsu (including the governor-general of the three-province Liangkiang region), and Shantung. "We have heard," it began, that

in the Chekiang region it is said that, when bridges are being constructed, some persons are secretly clipping such things as people's hair

and lapels for the purpose of casting spells for sinking the pilings. Now

this belief has spread into Shantung. These rumors are truly absurd. It may

be just petty thieves using the occasion to cast suspicion on others, so

that they may more brazenly play their clever tricks. However, this kind

of false story can easily delude and incite the public. Naturally it should be

rigorously investigated and forbidden, in order to put an end to evil

customs. Let it be known to the governors-general and governors in

those jurisdictions that they are to order their subordinates secretly to

undertake a thorough investigation. If this situation really exists, the

culprits should be arrested forthwith and punished severely. Or it may

be that arresting and severely punishing one or two ringleaders will

serve as warning to others. Also they must proceed as if nothing momentous

Were happening (pu-tung sheng-se), conduct their investigations in a proper

manner, and not permit yamen underlings to get involved and use the

occasion to stir up trouble and disturb local communities.'

A curious document: we are left in some doubt as to what His

Majesty "really" believed. Despite the "absurdity" of the rumors, he

believed it possible that someone was maliciously spreading them. Did he also believe that someone was actually attempting to practice

sorcery? Whatever else he may have believed, it is evident that foremost in his mind was the panic factor. A credulous public is easy to

"delude and incite." Officialdom must not only punish the rumormongers, but must do so without panicking the common people. The

final curiosity about this document is its conflation of the "bridgebuilding" and the "queue-clipping" images of' popular sorcery lore.

Whoever was Hungli's source of information from the South had

heard of both the masons of Te-ch'ing and the monks of Hsiao-shan.

Here too are linked, for the first time in an imperial document,

sorcery and the tonsure.

Information is power, but it is also security. Just as Hungli had his

own sources of information from Shantung, so the governor of Shantung, Funihan, seems to have had sources at court. It is too much to

accept as coincidence that the governor wrote his first report on

queue-clipping July 24, just one day before Hungli approved the

draft of his first court letter on the case. It was more likely a matter

of preemptive reporting: covering up information was a serious

matter between emperor and bureaucrat. The troublesome business

of local sorcery could have been kept from Hungli's attention only

at some risk of his hearing about it through the rumor network. Once

Governor Funihan had heard that Hungli had such information,

only speedy reporting could protect him from charges of conceal-

mnent.2 As it turned out, what Funihan had now to report went beyond

the spreading of "absurd" stories: actual sorcery had been attempted.

The Shantung Cases

Funihan had been going about his master's business of ensuring the

security of the realm. Having heard "in the fifth month" (mid-June

to mid-July) that there were persons in the provincial capital, Tsinan,

"clipping men's queues after stupefying the victims," he considered

that this was a matter of "evil arts" (hsieh-shu) that required swift

action. He immediately ordered local officials to investigate "secretly"

and to set a dragnet for the culprits. Later, while in the southern

Shantung city of Yen-chou inspecting troops, Funihan learned from

the prefect that in two counties of his jurisdiction, Tsou and Yi, two

beggars had been arrested for clipping queues. On the west, these

counties bordered the Grand Canal that carried grain shipments to

granaries near the capital. On the east, they lay beside the main overland route from Hangchow to Peking.' Funihan had the criminals, along with one of their victims, brought to the Yen-thou yamen,

where he interrogated them personally. The criminals, he reported,

made the following confessions, which became officialdom's window

upon the dark realm of sorcery. Here the identities of the mastersorcerers were first revealed, and upon these confessions was

founded the government's campaign.4

Ts'ai T'ing-chang Learns about Soul force

Far from his family home in Szechwan, beggar Ts'ai T'ing-chang's

strange adventures had begun while he was sojourning in Peking.

There he lived at the Lung-ch'ang Temple in Hsi-ssu p'ai-lou Street,

where he made a meager living selling his calligraphy. While there

he made the acquaintance of a monk named T'ung-yuan. Later,

unable to support himself, he left Peking for the South, and in late

March or early April encountered monk T'ung-yuan again, outside

the Grand Canal metropolis of Yangchow. With T'ung-yuan were

three other monks, his acolytes I-hsing, 1[-te, and I-an. T'ung-yuan

related that he had learned of certain sorcerers in Jen-ho, in Chekiang Province: one Chang and one Wang, along with a monk, Wuyuan, who knew marvelous magical arts. First you sprinkled a stupefying powder in a victim's face; while he was helpless you quickly

clipped hair from the end of his queue. Then, by reciting magical

incantations over the hair, you could steal his soul. By tying the soulforce-bearing hairs around paper cutouts of men and horses, you

could use the enlivened creatures as agents to steal people's possessions. T'ung-yuan told beggar Ts'ai that, back in Chekiang, monk

Wu-yuan had assembled a group of sixteen confederates, some

monks and some laymen, each of whom regularly set out to recruit

more followers and to clip queues. Evidently a large underground

network was spreading in the South.

Beggar Ts'ai (his confession continued) was persuaded to join

monk T'ung-yuan's gang and was taught. the magical incantations.

(Here was the essence of Chinese sorcery lore: a sorcerer's power lay

in techniques that anyone could learn.) T'ung-yuan, along with

beggar Ts'ai and acolyte I-an, now set out northward in hopes of

clipping queues along the way. When they reached the town of

Chung-shan-tien in Shantung's Tsou County, Ts'ai obtained some

"stupefying powder" from his master. He then went to a shop where a local man, one Hao Kuo-huan, was buying steamed bread. Ts'ai

sprinkled his powder in Hao's face and attempted to clip his queue

with a small knife. Pursued by the outraged and insufficiently stupefied Hao, Ts'ai was arrested by a local constable. In the confusion,

monk T'ung-yuan disappeared.

Chin Kuan-tzu Meets a Fortune-Teller

A native of Shantung's Chang-ch'iu County, in the metropolitan prefecture of Tsinan, beggar Chin Kuan-tzu had encountered an old

acquaintance in a nearby Taoist temple: Chang Ssu ju, a fortuneteller from the Kiangnan region. Fortune-teller Chang was accompanied by three confederates, all Shantungese. He told beggar Chin

that in Su-thou, Anhwei Province (not to be confused with Soochow

in Kiangsu, where the suspicious beggars had been arrested in May),

in the Dark Dragon Temple in the town of Shih-chuang, there lived

a monk called Yu-shih who had a magical technique for clipping

queues and tying up paper cutouts with them for the purpose of

robbing people. Beggar Chin was invited to join the gang. Fortuneteller Chang gave him a knife and a packet of stupefying powder

and told him to travel about clipping the queues of young boys. After

the band split up, beggar Chin got as far as the market town of Hsiao-

chuang-chi in his native county, where he abducted a young boy,

Chin Yu-tzu, and forcibly sodomized him. On July i, he reached Yi

County, where he clipped the queue of another young boy, Li Kou.

Shortly afterward he was arrested by county authorities.

In his memorial to the Throne, Governor Funihan noted the ominous possibility that the two sources of evil arts, one in Chekiang and

one in Anhwei, might spring from a single source: a dangerous

plotter lurking somewhere in the area. And the dark suspicion

occurred to him that sending gangs here and there, inciting and

deluding people into becoming their confederates, might not be

merely for the purpose of stealing goods. The conscientious governor

was sending secret memoranda to the governors of Chekiang,

Kiangsu, and Anhwei, as well as to the governor-general of the

Liangkiang region. The prisoners he was sending to Tsinan to be

interrogated further by the provincial judge and treasurer. Their

initial confessions were forwarded to the emperor, along with the

memorial reporting the arrests.5