Sisters in the Wilderness (13 page)

Read Sisters in the Wilderness Online

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Biography, #History

Thirty-five miles to the north, on Sturgeon Lake, there was a second covey of gentlefolk. Of the six settlers there, four were university-educated, one had attended an English military college and the last had “half a dozen silver spoons and a wife who plays the guitar,” according to one of the group, John Langton from Lancashire. Patrick Shirreff, a Scottish farmer who travelled throughout North America in the early 1830s, recorded that the society of the Peterborough region was reputed to be “the most polished and aristocratic in Canada.” What Shirreff implied was that there were far fewer loudmouthed Loyalists here than on the Front. The British class system had been partly transplanted to the Peterborough regionâwhich meant that Catharine and Thomas would feel comfortably at home in its upper ranks. Thomas might find a kindred spirit amongst the bookish Sturgeon Lake crowd.

Catharine's creeping anxiety about what lay ahead was evident in her account of the journey from the Front into the back country that she sent home to her mother. Girlish enthusiasm faded from her descriptions of a countryside that looked increasingly foreign. Although the gentle hills north of Cobourg reminded her of Gloucestershire, she deplored the “zigzag fences of split timber [which were] very offensive to my eye. I look in vain for the rich hedgerows of my native country.” As the afternoon wore on, and the woods each side of the road thickened, she began to wonder how any settler could clear the ground and build a log house within a single day, as Mr. Cattermole had airily promised.

Today, we can barely conceive how barbaric Catharine must have found the British North American frontier of 170 years ago. There are no sepia photographs to kindle our imaginations; only a few amateurish sketches capture the immensity of the wilderness. Ancient stands of white pine, many over one hundred feet tall and with trunks five or six feet across, dwarfed the puny efforts of early settlers to tame the dense

undergrowth of cedar and birch. Soon these giants would be felled by greedy lumber crews, eager to feed the appetite of Britain's Royal Navy for squared timbers and masts. But in 1832, the mighty trees towered like malevolent sentinels over a landscape broken up only by swamps, rivers, rocky outcrops, lakes and clearings created by forest fires. Often the only sound in the dead of a bitter winter night was the howling of wolves; often the nearest habitation was several miles away, through almost impenetrable bush.

Catharine huddled closer to Thomas as the horse-drawn wagon rumbled on. When they arrived at Rice Lake, her curiosity was whetted by the sight of an Indian village inhabited by Chippewa people (known today as Ojibwe, or in their own language, Anishanabeg). But her appetite for tourism was quenched when she got thoroughly chilled by driving rain as they crossed the lake on a grubby little steamer. Then the steamer, which continued up the Otonabee River, ran aground four miles below Peterborough. The men on the rowboat that eventually arrived to rescue them had consumed a whole keg of whisky and were “sullen and gloomy.” After an ugly row with the passengers, the men took off into the night, leaving Catharine and Thomas stranded in the woods. “We were nearly three miles below Peterborough, and how I was to walk this distance, weakened as I was by recent illness and fatigue of our long travelling, I knew not.”

Luckily, one of their fellow passengers knew where he was going. In response to Catharine's entreaties, he guided them through the dense forest to safety. It was an ordeal. At one point, Catharine lost her footing in the dark as she crossed a stream and fell into knee-deep water. And when they finally reached Peterborough, they found the principal inn there completely full. Thomas stood helplessly by as his shivering, wretched wife tearfully explained their predicament to the landlady. Catharine's gentle nature (plus the promise of a handsome reward from the Traills' savings) made instant friends: “we received every kindness and attention that we required from mine host and hostess,” she reported in her weekly letter back to Reydon Hall. The innkeeper and his wife “relinquished their own bed for our accommodation, contenting themselves with a shakedown before the kitchen fire.”

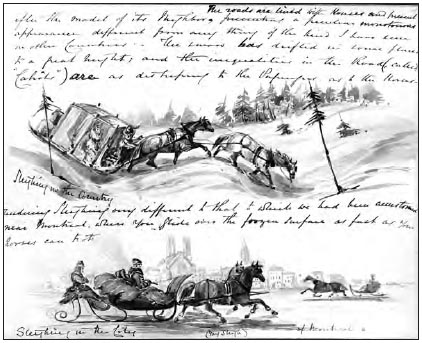

Travel in the New World was a rude shock for English gentry. Henry James Warre (1819â1898) contrasted his elegant Montreal sleigh (bottom sketch) with the bone-shaking experience of winter travel on country roads.

The following morning, a message was sent to Sam Strickland that his sister had arrived in Peterborough with her new husband. It took the boy who delivered the message all day to make his laborious way through the forests, along the roughly marked eleven-mile trail. Two days after Catharine and Thomas had reached Peterborough, a breathless and excited Sam arrived by canoe from his farm, after shooting the rapids of the Otonabee River, for a noisy reunion at the inn. He soon got Thomas organized. Thanks to Sam, Thomas had already secured a land grant of some waterfront acres on Lake Katchewanooka. Now his brother-in-law persuaded Thomas to spend some of his meagre capital on more acres that adjoined Sam's land, so their two farms would be contiguous.

Within three months of leaving the British Isles, the Traills had begun backwoods life with a wonderful advantage: they didn't have to start from scratch. They had a neighbour who knew what he was doing, and who could lend them the agricultural implements (axes, ploughs, scythes) with which they were completely unfamiliar. Moreover, unlike most early settlers, they were able to spend their first year in the bush not in a leaky, cramped shanty but first as guests of various friends in Peterborough, and then in a sturdy log cabin near the Stricklands that had been abandoned by another family.

Irish-born Frances Stewart became a close friend to Catharine as soon as the Traills arrived in Douro Township

The Stricklands' hospitality sweetened the Traills' first taste of pioneer life. The Reids and Stewarts formed a little clique into which Catharineâgenerous, kind and always willing to lend a hand with jam-making and bread-bakingâwas soon absorbed. During the early weeks in Peter-borough, Catharine quickly became close friends with Dublin-born Frances Stewart, who was eight years older than she was and already the mother of eight children (she would have eleven children altogether, all of whom would survive childhood). Frances shared all Catharine's religious, literary and botanical interests. A relative by marriage of the novelist Maria Edge-worth, Frances and her husband Thomas had moved to the unbroken bush of Douro Township ten years earlier, when Peterborough scarcely

existed. Frances knew all too well how wretched a woman like Catharine would feel as she faced the rigours of life in the backwoods. In 1823, Frances herself had written home: “This place is so lonely that in spite of all my efforts to keep them off, clouds of dismal thoughts fly and lower over me. I have not seen a woman except those in our party for over five months, and only three times anyone in the shape of a companion.”

Frances, a spry little woman with a ready smile, quickly became Catharine's confidante, ready to comfort her when she unburdened herself about her homesickness for East Anglia, her impatience that letters from home took more than two months to reach her, her unhappiness that there was no church at which she could attend services. However bad Catharine found the bush, she had to acknowledge that her new friend had found Upper Canada in a far more raw state. Frances had drawn on her deep faith in a protective God to sustain her, and on her extensive knowledge of natural science (she had studied chemistry, botany and geology as a child) to catalogue the plants around her.

During the 1820s, the Stewarts had watched the local population swell and had built themselves a comfortable log house on the Otonabee River, a home they named Auburn. By the time the Traills arrived in Peterborough, Auburn's every shelf and wall was lined with collections of dried flowers and grasses, Indian bows and arrows, dried skins of small furry animals, bear claws, eagle wings, antlers, fossils, rock and crystal specimens and Indian pottery. All winter a huge fire blazed in the hearth, while children played on the floor and an infant slept in an Indian cradle.

Frances provided Catharine with the support Thomas could never offer and Catharine knew she could never ask of him. Auburn became Catharine's haven, and an example of what she wanted to create in the backwoods. At Auburn, she could play Frances's piano (the only one for miles around) and compare specimens of flora and fauna with her friend. Soon it became a game for the Stewart children to present her with bits of moss, curious leaves or petrified shells. “Ooh, Mrs. Traill,”

they would say, mimicking her enthusiasm, “Here's a wee mite.” Catharine learned from Frances “how much could be done by practical usefulness to make a home in the lonely woods the abode of peace and comfort even by delicately-nurtured women, and energetic, refined and educated men.”

After the Traills moved the eleven miles north, to Lake Katchewanooka, Catharine saw much less of Frances. The long walk along a roughly blazed trail was not an inviting prospect, particularly in the short winter days. It was too easy to get lost. Catharine was soon absorbed into another circle of pioneers: the Stricklands, Shairpes and Caddys, who were hacking a living out of the untamed bush. The presence of another woman was a huge boost to the women in this pioneer settlement, all of whom were locked in an exhausting and endlessly fertile cycle of annual childbirth. Catharine's sister-in-law Mary Reid Strickland already had three children and was pregnant with her fourth (eventually she would have fourteen babies, three of whom would die as infants). And in June 1833, Catharine's own first baby was born. Newborn James was “the joy of my heart and the delight of my eyes,” as Catharine described him to the Birds, in Suffolk.

By the time the new cabin on the Traills' own property was finally ready for occupancy in December 1833, Catharine had recovered her optimistic belief that she and Thomas could conquer the wilderness. Scarcely a day went by without her sitting down to write lengthy descriptions of life in Upper Canada to her mother and sisters in England. The letters brim over with the same cheerful enthusiasm that, by now, Catharine had decided it was her marital duty to provide for her husband.

Chapter 6

“Yankee Savages”

T

he mere thought of the wilderness appalled Susanna. The Moodies arrived at Cobourg on September 9, a week after the Traills had left. During her first few days there, she was so depressed by gruesome tales of the back country from Tom Wales and others that she decided even the skin-deep “civilization” of a small town was preferable to the bush. After all, unlike Catharine, she already had a small baby to care for. And Cobourg, with its newspaper and library, offered more hope of a literary career than some backwoods settlement could ever promise.

It didn't take long to persuade John that they should stay put for a while. Her husband was easily convinced that he would do better to try land speculation rather than backwoods farming. Gregarious and chatty, he felt he had more hope of succeeding as an enthusiastic salesman than as an ignorant farmer. So he shelved his original intention of immediately

applying for the free land to which he was entitled, especially since all the available plots close to the Front had been taken up years earlier. Instead of following the Traills into the back country, the Moodies looked around for a property they could afford where the land had already been cleared and buildings erected.

John and Susanna settled into Cobourg's Steamboat Hotel. The talk in the saloon was all of lots and concessions, acreage and mortgages. John was soon in the thick of it, buying drinks for all the promoters who hung around the smoky parlour, convinced he was going to get a good deal. By the end of September, the Moodies had plunged into the settlers' life: John paid three hundred pounds to a land-dealer for a cleared two-hundred-acre farm on the edge of Hamilton Township, eight miles west of Cobourg and four miles east of the smaller waterside settlement of Port Hope. (At this stage, when both dollars and pounds were circulating, the exchange rate was roughly five dollars to the pound. As a general rule, early eighteenth-century amounts in Upper Canada should be multiplied by one hundred to determine their contemporary equivalentâalthough, like the British rule, this is a rough-and-ready approximation. Three hundred pounds in 1832 would therefore be worth about $150,000 today.) With his usual blithe optimism, he named his Canadian “estate” Melsetter, after the Orkney home in which he was raised.