She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England Before Elizabeth (32 page)

Read She-Wolves: The Women Who Ruled England Before Elizabeth Online

Authors: Helen Castor

John had none of his brother’s military genius, and few decisive military manoeuvres to his name. But this threat to his mother animated him into sudden and brilliantly resolute action. With the help of the unlikely pairing of Aimery de Thouars and Guillaume des Roches – former rivals whose support he would not have had, had it not been for Eleanor – John led his troops on a forced march of eighty miles in less than forty-eight hours to

arrive at Mirebeau, unheralded and utterly unexpected, during the night of 31 July. As dawn broke they stormed the town, falling upon Arthur’s soldiers while they slept, and seizing Hugues de Lusignan as he breakfasted on a dish of pigeons. Within hours Arthur and de Lusignan were John’s prisoners, along with all their men, and Eleanor was safe, and free.

It was the last time she would walk on a public stage. After the shock of her narrow escape, age and exhaustion caught up with her at last. She did not press onward from Mirebeau into Poitou, but returned to Fontevraud to rest, and to contemplate the prospect of the brightness of heaven rather than the storm-clouds that were gathering over her son. With the loss of his mother’s active support, John lost too the speed of purpose and the maturity of judgement that he had shown at Mirebeau. Revelling in the glory of his success, he refused to allow des Roches and the viscount of Thouars any part in deciding the fate of the prisoners, many of whom were their countrymen – a mistake that served to confirm John’s habit of undermining and alienating allies whom he should instead have nurtured and exploited. Just two months after Mirebeau, des Roches and Thouars abandoned him; and within weeks they had wrested Angers from his control. John tried to forge a new relationship with the Lusignans in their stead, but it was hardly surprising that his bitterest enemies met his overtures with dissimulation and disloyalty. At the end of 1202 John once more retreated to Normandy. At Mirebeau, he had held the keys to Anjou, Maine, Touraine and Poitou – the heart of his father’s French empire, and the gateway to his mother’s duchy – and he had thrown them away.

Worse was to come. Rumours began to fly concerning the fate of his nephew and rival, Arthur, who had disappeared as a prisoner into John’s forbidding network of Norman fortresses. Whispers told of a drunken John, in a sotted rage, stoving in the boy’s skull before dumping the blood-soaked corpse into the Seine. Support for John was already haemorrhaging because of his paranoiac unreliability, but revulsion at the murder now opened another gushing vein. Meanwhile, the harrying of Normandy’s easternedge

by the French turned, in the summer of 1203, into a steady advance. Philippe had never been a warrior in the mode of his lionhearted enemy Richard; the French king was a tense, physically cautious figure, without chivalric glamour or easy camaraderie. But, warrior or no, what he achieved in the next twelve months was radical, even revolutionary, in its effect. On 6 March 1204, Château Gaillard – Richard’s ‘saucy castle’, new-built on a jutting crag overlooking the Seine at Les Andelys – fell to the French after a six-month siege. The loss of this supposedly impregnable stronghold served to open the gates of towns and citadels across Normandy to Philippe, as the duchy’s inhabitants realised that John – who had ignominiously retreated to England in December 1203 – would not or could not protect them. The unthinkable had happened: the Norman dynasty which had so ruthlessly seized the English crown no longer ruled its Norman homeland.

Two hundred miles further south, Eleanor retreated into silence. For the first time in her life, the world that mattered most to her now was the next one. But, beyond the fact that she took the habit of the nuns who had welcomed her to their midst at Fontevraud, we know almost nothing about her last weeks. We cannot tell whether she was aware, in her final days, of the collapse of her husband’s empire in the unsteady hands of her youngest son. All we know is that on 31 March 1204, at the age of eighty, Eleanor of Aquitaine closed her eyes for the last time. She was buried in the abbey which had become a home to her, beside her husband Henry, her son Richard and her daughter Joanna. The calm with which her graceful effigy held in its hands an open book as it lay alongside theirs marked a cool counterpoint to the violent passions which had fractured her family in life.

And that contrast was a fitting memorial to Eleanor. Always a political creature, she had begun as a charismatically unpredictable force of instinct and will – qualities which the trials of her long incarceration had tempered with a sophisticated diplomatic sense and what came to be the surest of political touches. The woman whose rebellion against her own husband had once threatened,

it seemed, to overturn the natural order of creation had in time become the mother of the English kingdom, and the watchful guardian of her beloved Aquitaine. Eleanor had stood alone to embody the crown in England when its king was feared lost to a German jail; and she became the first woman to kneel in homage to a feudal overlord, to underpin the security of her duchy after six decades as its duchess.

If John needed any reminder of his mother’s extraordinary talents, it came in the months after she died. Not only was the fall of Normandy confirmed beyond all possible doubt when Philippe rode into Rouen just eleven weeks after her death, but Poitou too began to slip through John’s fingers as its towns and lords, bereft now of the protection of their lady, scrambled to offer their allegiance instead to the French king. And in the south-western stretches of Aquitaine the troops of Alfonso of Castile were on the march to claim Gascony as the supposed inheritance of his wife, Eleanor’s daughter and namesake.

Jean Sans Terre

, they called him; by now, it was no expression of sympathy but a damning verdict on John’s catastrophic military losses. Yet this most unlovely king of England did not quite lose all his lands across the sea – and here too we might find an echo of Eleanor’s capabilities. Normandy and Anjou, the homelands of the kings who had ruled England for more than a century, were gone. The historian William of Newburgh believed that Nor mandy had fallen prey to French aggression while King Richard was a prisoner because ‘the courage of that ancient and most valiant people now languished, since they had neither duke, nor head, nor chief ’, and the same could have been said (had William of Newburgh lived to tell the tale) of both Normandy and Anjou under the suspicious and inconstant command of John. But Aquitaine had had a head and a chief – not a duke, but a duchess – for nearly seventy years. And when the dust settled on the debris of John’s empire, it was Eleanor’s land of Aquitaine – battered and bloody, but still standing – that remained to the English crown.

Iron Lady

1295–1358

It was a cold day in Boulogne, 25 January 1308, when two of Eleanor’s descendants met in the cathedral church of Our Lady to exchange their wedding vows.

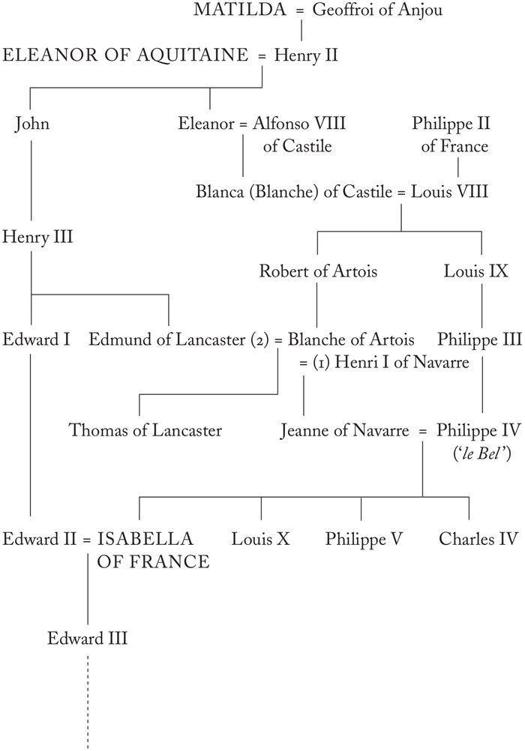

The bridegroom, King Edward II of England, great-grandson of Eleanor’s son John, was a tall and handsome figure, powerfully built and gorgeously dressed. He was a young man, still not quite twenty-four; but his bride, at half his age, was little more than a child. Like Eleanor’s granddaughter Blanca, from whom she could trace her descent, this twelve-year-old princess stood before the altar with her royal husband as the living embodiment of an Anglo-French alliance. Isabella of France was the only daughter of the French king Philippe IV, known to his subjects as ‘

le Bel

’ – the Fair – for his statuesque good looks. Despite her youth, it was already clear that Isabella had inherited her father’s beauty, and her slight frame was made luminous in the candlelight by a jewelled robe of blue and gold and a crimson mantle lined with yellow.

They were a golden couple, young and strong enough, it seemed, to bear the hopes and expectations that weighed on this marriage. The match had first been proposed a decade earlier, when Isabella was still in the nursery, as a means of bringing peace to yet another conflict over the king of England’s rights to Aquitaine and his duty to his predatory overlord, the king of France.

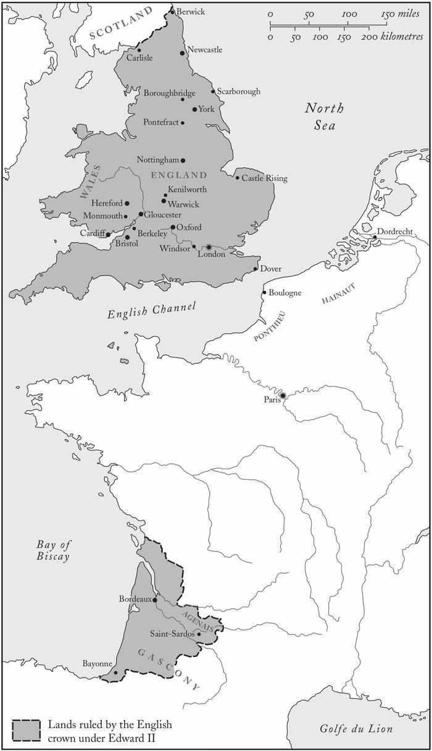

Edward’s father, the first King Edward, had harboured ambitions for his role across the Channel worthy of his Norman and Angevin forebears, but the territories he ruled there constituted only a fraction of the empire over which Eleanor’s husband and sons had once fought so bitterly. John’s loss of Normandy, Anjou and Poitou had never been reversed, and King Edward, as duke of

Aquitaine, found himself in possession only of the duchy’s southwestern province of Gascony, stretching along the Atlantic coast from the great city of Bordeaux to the southerly port of Bayonne.

This first Edward had been a mighty warrior, but fortune had cast military opportunity his way to the west and the north of his kingdom rather than southward across the sea to France. When the native princes of Wales tried to throw off English overlordship, he responded with a full-blown war of conquest, pinning down the principality with a chain of awe-inspiring castles, from Harlech’s monolithic grandeur to Caernarfon’s polygonal towers, designed in homage to the walls of Constantinople. Meanwhile, in the independent kingdom of Scotland an unexpected succession crisis gave Edward – a wolf invited through the door as arbiter between the rival claims of Robert Bruce and John Balliol – the chance to decide that the Scots too deserved the benefit of forcibly imposed English rule. With his energies fully occupied elsewhere, Edward’s relations with France remained civil and uncontroversial – until in 1294 Philippe IV seized his moment to occupy Gascony and declare the duchy of Aquitaine forfeit to the French crown.

For three years, England and France fought an unhappy war. The cost to both sides was high in men, money, and, for Edward, political as well as financial capital, since he was simultaneously fighting at full stretch to suppress rebellion in Wales and tenacious resistance in Scotland. Peace, when it came in 1297, was a relief; and it was confirmed in 1299 with the celebration of one wedding – when Edward, at sixty, took Philippe’s seventeen-year-old sister Marguerite as his second wife – and the promise of another, through the betrothal of little Isabella to the young prince who was heir to the English throne.

Now, in January 1308, that prince was a king. Edward I, indefatigable to the end, had died five months earlier on his way to fight once again in Scotland, leaving his son to succeed him as Edward II. And Isabella was at last old enough to become a wife and a queen. As they stood in the hushed cathedral, it seemed that a new dawn was breaking with the accession of a monarch whom

‘God had endowed’ (said the well-informed anonymous author of the

Vita Edwardi Secundi

, a contemporary Latin account of Edward’s life) ‘with every gift’ – including, now, the hand in marriage of the French king’s exquisite daughter.

All, however, was not as it seemed. For those who cared to look, there were signs aplenty that the dazzling ceremony at Boulogne glittered with empty artifice rather than political promise. Edward shared his father’s name – an unusual Anglo-Saxon throwback, thanks to his grandfather’s reverence for the saintly eleventh-century king Edward the Confessor – but in other ways he resembled him little. He was the last-born of his parents’ fourteen children, and three older brothers – John, Henry and Alfonso – had died in turn before they had had a chance to try their hand at the business of ruling. Edward alone was left to shoulder responsibility for England’s future. And already, before his father’s death, he had begun to disappoint.