She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me (7 page)

Read She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me Online

Authors: Emma Brockes

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Adult, #Biography

I glance down the page. In the bottom left-hand corner is something I recognize instantly. Apart from the poem, the only other thing of her father's that my mother kept was his copy of

The

Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

. He had signed it, I remembered, on the flyleaf. I go to the bookcase, pull it out, and, returning to the window, hold it up against the charge sheet. Under a heading of previous convictions, there is a single entry for housebreaking and theft, with a twelve-month suspended sentence. “I admit the previous conviction,” the murderer has written, signing his name underneath. The signatures are the same.

I read on. The murder was of an old man and took place in the course of a robbery. The three accomplices had identified the remoteness of the farm and the vulnerability of the victim and struck without mercy. It was, said the judge, unforgivably brutal. He had considered applying the death penalty, then relented and gave each of the men ten years with hard labor.

There follows a thick sheaf of paperwork, most of it depositions by witnesses. The three men had been spotted at the railway station and by various laborers on the road up to the farm. When they were caught, they were in possession of a firearm and the old man's money. There were no details of how much of that decade-long jail term was served, but my grandfather must have been released early. I look at the date of sentencing. My mother was born six years later.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

I HAVE NO IDEA

if my mother knew about the murder. I have a dim recollection of her telling me her father had been to jail once, but for what I don't knowâalthough I have an even dimmer memory of her saying he was fired from various jobs and locations for “interfering” with children he had access to.

In any case, any doubts I had about going to South Africa are resolved by this paperwork. It is one thing to have a researcher photocopy and send me pretrial notes from the murder; the murder is impersonal. But the idea of someone providing a similar service for the second trialâof potentially reading my mother's testimony in the action she brought against her father before I doâis unthinkable. I will have to go to Pretoria and read whatever is in the archives for myself.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

JOURNEYS LIKE THESE

should take months of planningâtrips to travel agents, consultations of maps and with shamansâbut ten minutes on the Internet and it's done: flights, hotel, even an e-mail to a man who used to work with my mother at the law firm in Johannesburg. He writes back instantly to say he remembers her well and would be delighted to have lunch when I come in the new year. I feel vaguely embarrassed; after all these years, is this all there is to it?

I ring the South African consulate to ask about visas, and they suggest something that hasn't occurred to me: that if my mother's paperwork is in order, I can apply for dual citizenship. I have a visceral reaction, followed by a second, guiltier one. I put the phone down and ring my friend Pooly. “They offered me a passport,” I say.

She bursts out laughing. “And?”

“I know it's a new era and all, butâ”

“What?”

“Ugh. âSouth African passport holder.' Makes me feel physically sick.”

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

AT THE WEEKENDS

I go home to Buckinghamshire, out on the Friday-night train and back again on Sunday. It is a journey I've made hundreds of times. Now it turns into a clichéâwoman looks through train window at familiar landscape made alien by sad thoughts about death. My memory of those months from July to September is reduced almost entirely to being on the train every weekend, watching the bleached walls of the council estate go from ash gray in the sun to pewter in the rain, and the derelict lots, with their mountains of scrap metal, burnish and blacken. The new Wembley Stadium is being built in the distance and gets higher each week. London bleeds into the suburbs and then the greenbelt: the spire at Harrow, the allotments, the back end of the private school, the pub garden. My favorite part of the journey comes forty minutes in, when the train emerges from tree-covered escarpments into a clearing with views across the valley. It looks like the opening scene from a Jane Austen adaptation. My spirits soar. I am two stops from home.

Before my mother died I would round the corner and see her head in the window, and she, eagle-eyed, waiting, would wave. The window looks blank now. Friday night passes somehow and then, on Saturday, while the weather holds, my dad and I go on long walks. We go along the canal for the first time since I was a child. We go up the hill behind Chequers, and climb over the fence to the summit. There are sheep up there, and we wonder to whom they belong. You can see right down into the prime minister's residence. We joke about snipers. We go across the fields by the air force base, yellow stubble underfoot, dry hay in the air, and across the cricket field behind the station. We don't talk much, just walk and stop at the pub for lunch or a drink.

We go all the way along the ridge to the beacon at Ivinghoe. The weather is on the turn by then and it is blustery enough to hold out your arms and lean into the wind. One weekend, we go the steep way up the hill behind the house where we scattered her ashes. On a clear day you can see across the Thames Valley from here, all the way to County Hall.

One Sunday, my father and I drive over to Henley to take his parents out for lunch. It is the first time we've seen them since my mother's death, and although they are kind, they don't mention her, either her death or the fact of her ever having lived. I think how she would have loved this, confirmation of what she had been saying for the best part of thirty years, about the English generally and her in-laws in particular: “My family are weird, God knows, but this lot are weirder.”

During the week, I walk to work instead of taking the bus. It is better to be moving; sitting still risks opening the door to reflection. I retreat to the most ordinary of memories: standing in line for the park-and-ride in Oxford, waiting for the bus, boarding and sitting in it. That's the entire memory. My mother is in a blue three-quarter-length coat, a brown cashmere scarf my father's brother gave her for Christmas, and Ecco shoes, in which she has put neon-green laces. I don't know why I remembered it, beyond that I must have been happy, anticipating the day we would spend together, looking at colleges before I filled out my university application forms.

There is another, more complicated image I keep looping. Six months earlier, my mother had come up to London to help me buy a sofa. It was one of those early-spring days of freak heat wave, and London was smoldering. There were roadworks everywhere. My mother had worn a coat too warm for the day, a padded green jacket with a brooch in the shape of a fox on the collar. I told myself she had merely failed to look at the forecast, although she wasn't eating enough then to stay warm. All morning we walked up and down the Tottenham Court Road, getting nowhere. Heal's was too expensive. Everything in Furniture Village was dark and heavy, with a cheap finish. There was nothing in Habitat.

By mid-afternoon, we were exhausted and my mother was keen to get back. She was late for the train, and with half the Underground shut for track maintenance, we waited in the heat outside Edgware Road Station for the replacement bus service to Marylebone. We should have taken a taxi. I wish we had. I thought the satisfaction of doing it the hard way would outweigh the discomfort, but on the bus halfway there I saw I'd miscalculated. As we shuddered and lurched down the Marylebone Road, the air boiling around us, I saw something like panic cross my mother's face, followed by regret for letting the side down. We got to the station so late that, after leaving me at the barrier, she had literally to sprint the length of the platform to catch the departing train. I watched her run with a sudden, leaden awareness that everythingâthe heat, the panic, the retreating back in a jacket too warm for the dayâwas something I would remember, when remembering became necessary. It was the last of the ordinary days.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

ONE FRIDAY EVENING,

I don't take the train. I stay in London and go to the launch of my godfather's art show, where an old friend of my mother's hands me an envelope. It is photos of her he found and thought I might like to have, from an early holiday they took in Portugal or Spain. I've heard about these holidays. On one, my mother and godfather read

Portnoy's Complaint

on the beach and both cried. On another, her long hair bleached blond by the sun, men followed her through the streets of Lisbon, clicking their fingers and propositioning her. This was “before Portugal opened up,” she would say grandly, and how much it annoyed my godfather had delighted her.

“I'm not doing anything,” she had said innocently when he hissed at her to stop.

I have never seen these photos before, although I've seen one of her from a few years earlier, just before she left South Africa, when she was a bridesmaid at her friend Denise's wedding. She had looked slightly spinsterish then, with a terrible 1950s hairdo and unflattering bridesmaid's garb. In these she is modern, sleek, with an almost catlike expression. There is a startling shot of her standing in a black ankle-length negligée on a vine-strewn terrace. The negligée is transparent and she isn't wearing anything underneath. I have a surge of primness; for God's sake, mother, put some clothes on. I wonder if she is having a breakdown. I study her face. She looks coy, as she always did in photos, but pleased with herself, serene. In another photo, she stands on the beach in a jaunty orange tunic, feet firmly planted in the sand, bag swinging, my godfather standing beside her in a pair of swimming trunks. I have a dizzying sense of the largeness of the life led before I came along.

One rainy autumn day, I take the train to a town an hour outside London. My mother's cousin Gloria and her husband, Cyrille, are in England, visiting their daughter and son-in-law. It was Gloria who sent my mother the painting and the teacup, the little items from her mother's estate, and it was Gloria's mother, Kathy, who spent all those years trying to track my mother down. Gloria grew up with the legend of her disappeared cousin, and when she catches sight of me in the station car park, her eyes fill with tears. “Oh, my heart could just break.”

Gloria is small and ferociously family-oriented. Years earlier, she and Cyrille came to stay with us for a few weeks. I remember them as kind, generous peopleâthe personification of the good side of the family. Gloria remembers that trip primarily for my mother's short temper. My mother was very fond of Gloria; she was a link to her own mother, which didn't stop her shouting at her cousin for taking too long to get ready and then laughing at the old-ladyish rain hood she put on.

“She had such a sharp tongue!” says Gloria, over tea in her daughter's house. “Just like my mother.” At seventy, Gloria is still reeling from some of the sharper things her mother said to her over the years.

Gloria does not have a sharp tongue. She is infinitely kind. She is involved in a church group. I see her do a brave thing now, which is, knowing my mother's feelings about religion and correctly intuiting mine, to say, “I know you don't want to hear this, luvvie, but Jesus does love you.”

Gloria is the memory of that side of the family, and as we settle in for the afternoon, she tells me about it. I have never heard any of this and am fascinated. The first Doubell anyone can remember, says Gloria, is Bebe, said to have fled from France to England after killing a man in a boxing match, and from there on to Africa, sometime in the early nineteenth century. Several generations later, his descendants boiled down to eight siblings: Daniel, Samuel, Benjamin, Francis, Johanna, Anna, KathleenâGloria's motherâand the youngest, my grandmother, Sarah Salmiena Magdalena Doubell. She gave birth to my mother in Kathy's house, attended by Dr. Boulle, the railway physician, and his midwife, Sister Cave. I burst into laughter. “Boulle and Cave?” I say.

Gloria laughs. “Yes.”

“They should have had a magic act.”

Gloria was delivered by the same duo, in the same bed, in the back bedroom of the house she grew up in. “Oh, my mother loved your grandmother,” she says. “Sarah was the baby of the family. It broke my mother's heart when she died.”

Gloria remembers clearly the first time she met my mother. It was at the airport in Durban. My mother had flown down there from Johannesburg at the tail end of her trip in 1977. She would be meeting members of her mother's family for the first time. When she spotted Gloria across the concourse, she had to sit down on her suitcase abruptly; her legs buckled under her.

“When I think of what happened . . .” says Gloria, tearfully. “She had a terrible life.”

“But I don't think she did, Gloria!” I say in astonishment. I've never had to defend my mother's happiness before. It is strange to hear a rival view of her. “I think she knew how to be happy.” It is also strange to be talking like this, around forbidden subjects and in my mother's absence. I wonder if she'd be angry.

Gloria urges me to come and visit them in Durban when I arrive in January, and I say that I will. She gives me food for the train. On the way back, I look out the window and think of the pride with which she related the family history. I think of her unquestioning concern and generosity toward me. And I think of her mother, Kathy, who my own mother admired so much. Whatever else happened, I think, the baby who became my mother had, at least, been born into love.

“All her life my mother asked,” Gloria had said before I left, “all her life she asked, âWhere's Pauline? What happened to Pauline? I wonder where Pauline is now?'”

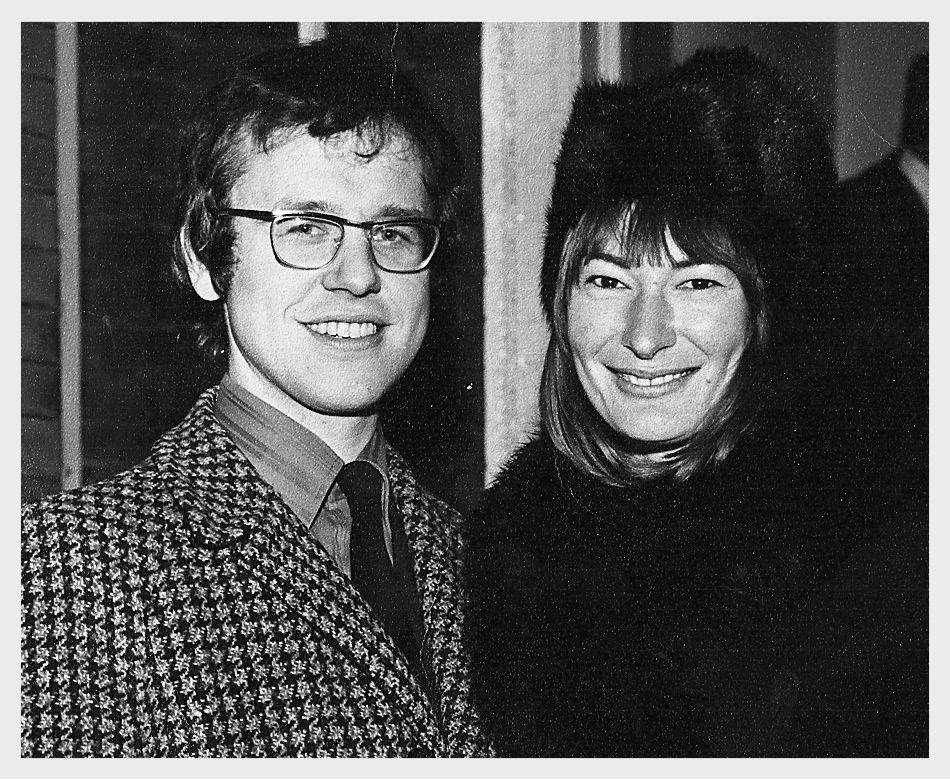

Mum and dad on their wedding day, outside Kensington Registry Office.