She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me (3 page)

Read She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me Online

Authors: Emma Brockes

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Adult, #Biography

After my mother had arrived in England, but before she had met my dad, she had gone to see a healer, a retired postman and “humble little man,” she would say (as if we were royalty), who lived in a council flat in Tottenham. She didn't believe in all of that; on the other hand, you never know, and so, on the recommendation of a friend whose back he'd fixed, she went to see Mr. Trevor.

His visions came out in flashes over tea. She would have one child, he said, a girl with long fingers like a starfish (true). She would face a fork in the road one day, and depending on which branch she took, be either very happy or slightly less happy (the former, I hope). At some point in the session, Mr. Trevor came over peculiar and in a horrible voice said, “Is that dirt or a birthmark?”

“That was your father,” he said, coming to. Her father was dead and had in any case never been to England. Mr. Trevor couldn't possibly have delivered his mail.

Whenever she told this story, she would lift her hair and show me, at the nape of her neck, a strawberry-colored birthmark that had survived her father's best efforts to scrub it off. Those were always the words he would use, she said.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

LETTERS CAME IN

from her siblings occasionally; nothing for years and then a fifteen-page blockbuster written entirely in capitals. She would leave it on the kitchen table for me, for when I got home from school. “Read it to me,” she said, and I would.

To me, her siblings had a kind of mythical status, partly for the glamour all large families hold for only children, and partly for their complete and utter absence from our lives. When my mother talked about them, it was as though they were people she had known a long time ago and had been very fond of, once. There was the one she called her best friend. There was one who was her conscience. There were two she hardly knew. There was one who'd died of whooping cough as a child, whose small white coffin she remembered walking behind. There was one who was very charming but whom you had to keep an eye on. There were two she called her babiesâ“Fay was my baby, Steve was my baby”âwhom she'd brought up, more or less, when her stepmother's hands were full.

There were no photos of these people on display in the house, but she did once dig out a cardboard box from the garage to show me some old sepia-colored photos from an even earlier era. This, she said, was before her mother had died and her father remarried and had so many more children.

There were three or four in the set, small, white-bordered, and faded with age. One was of my mother as a baby, standing in a hot-looking crib, clutching hold of the bars. In another she was standing, waving, in a garden. On the back, my grandmother Sarah had written, “Pauline on her 2nd birthday.” There were two further photos in the set: my mother as a toddler, with fat little legs and scrunched-down socks, standing beside a fresh grave, the soil still exposed; and in the same position on a different dayâthe grave already looked older. Someone had written on the back, “Pauline arranging flowers on her mother's grave,” but who that was she had no idea. “Shame,” said my mother, when she showed me the photos, “poor little thing,” as if it were not her we were looking at but someone entirely unrelated to either of us.

Mum putting flowers on her own mother's grave.

I remember asking her once if we had any heirlooms. It was a word I'd picked up from a friend while tiptoeing around her parents' formal drawing room one day, where we weren't allowed to play. My friend had pointed out various spindly legged chairs and silver trinkets that had been her granny's and which, she said importantly, would be hers one day. I had gone back to my own house and, while my mother considered the question, had looked around for something old to cherish.

“What about this?” I said. It was a green cigar box in thick, heavy glass with a brass hinge.

“For goodness' sake,” said my mother. She didn't know where it came from, and anyway, it was hideous.

We didn't have heirlooms, she said, because she could fit only so much into her trunk, and besides, her mother had died when she was two, what did I want? I was goading her a little, I knew it. Our peculiarities were annoying me that day. Of this particular friend of mine's mother, my own mother had been known to say, “I don't know why she's so pleased with herself. They made their money in gin.”

Actually there were a few things she could have pointed out to me. There was a tiny porcelain teacup, the sole surviving item from a doll's tea service, with a depiction of the young queen, then Princess Elizabeth, on the side. There was a glass-beaded necklace. And there was a portrait of her mother, Sarah, that hung above the TV in the lounge. It was blown up from a black-and-white photo and painted over in color, in the style of the times. The colors were a little offâthe lips too bright, the skin too pale; she looked consumptive, which in fact she was. My mother didn't mention these items in the talk about heirlooms. They must have struck her as a mean inheritance, the pitiful remains of a long-dead young woman, and when I thought about it later, I was sorry for asking. Later still, I thought about the painting and where she had chosen to hang it; whenever my mother raised her eyes from the TV, she met her own mother's gaze.

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

THERE WAS, IN FACT,

something my mother wanted me to have by way of an heirloom. It had come over on the boat with her in an old-fashioned trunk, the kind with its ribs on the outside. “All my worldly goods,” she would say, and when one of these things surfaced in the course of daily life, a moment would be taken, as before an item recovered from Christ's tomb.

Before I moved countries myself and understood the pull of sentiment over practicality, I thought her packing choices eccentric. So no overcoat, although she was sailing into an English winter, but a six-piece dinner service. The complete works of Jane Austen, minus

Mansfield Park

. A bespoke two-piece suit in oatmeal with brown trim. A tapestry she had done, even though she wasn't arty, of a seventeenth-century English drawing-room scene in which someone played the harpsichord and someone else the lute. And at the bottom of her trunk, wrapped in a pair of knickers, her handgun. Getting it through customs undetected was her first triumph in the new country.

The gun was kept in a secret drawer beneath the bookcase in the downstairs guest bedroom, the most secure of the improvised safes in the house. In my parents' bedroom, a decoy tumble dryer contained some gold and silver necklaces under a pile of citrus-colored T-shirts and a terry-cloth tracksuit whose shade we called aquamarine. Outside the bathroom, in the cavity between two plastic buckets that served as a fortified laundry basket, were my mother's gold bracelets. For a while, she stashed things in the ash collector beneath an unused fireplace in the dining room, but couldn't shake the fear that she would die suddenly and we would forget what she had buried there, sending it up in smoke. I forget what she buried there. Not the rings we called knuckle-dusters, with huge semiprecious stonesâtopaz, amethyst, tourmalineâon tiny gold and silver mounts. They weren't valuable or even wearable, but they were very pretty, and most of them had been given to her by friends or sent in padded envelopes across vast distances of space and time by relatives who thought she should have them. The person they'd belonged to must have died, but who that was I don't know.

The secret drawer, which she had designed herself after consulting the carpenter, was where she kept her most precious items: her naturalization papers; a list of how much I weighed during the first six months of my life; various documents testifying to her abilities as a bookkeeper; and the gun.

“Remember it's here,” she said, the one time she showed it to me. “And remember my jewels. Don't let your father's second wife get her hands on them.”

“Ha!” called my dad from the hallway. “I should be so lucky.”

My mother smiled. “You'll miss me when I'm gone.”

It was smaller than I'd imagined, silver with a pearl handle, like something a highwayman might proffer through a frilly sleeve during a slightly fey holdup. I knew it was illegal, but gun licensing wasn't the issue then that it is now and it struck me as naughty in the order of, say, a white lie, rather than something genuinely criminal, like dropping litter in the street or parking on the double yellow lines outside the liquor store. She had it, she said, because “everybody had one.” I think she saw it as a jaunty take on the whole stuffy English notion of inheritanceâjust the thing for a woman to bequeath to her only daughter. My dad hated having it in the house and threatened, once, to throw it in the local arm of the Grand Union Canal.

“You'll do no such thing!” my mother raged. “I'm very fond of that gun.”

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

IT WAS ABOUT A YEAR

after this that she stood in the kitchen cooking the sausages, face flushed from the heat pulsing out of the grill. My dad was watching TV in the next room. “Go and change,” she had said when he came in from work, as she said every night. Without turning and in a voice so harsh and strange she sounded like a medium channelling an angry spirit, she said, “My father was a violent alcoholic and a pedophile who . . .” The rest is lost, however, because at the first whiff of trouble I burst loudly into tears like a cartoon baby.

Something unthinkable happened then. My mother, who at the slightest hint of distress on my part would mobilize armies to eliminate the cause, who routinely threatened to kill people on my behalf and who felt, I always thought, shortchanged that I never gave her an opportunity to show me exactly what she could do in this area, didn't move across the floor to console me, but stood staring disconsolately into the mouth of the grill. “Your father cried, too, when I told him,” she said, and I could see there was consolation in this, her sense of being surrounded by weaklings. Abruptly I switched off the tears. My dad came in. We ate dinner as normal. We didn't talk about it again for fifteen years.

Except that we did, of course. “The absence from conversation of a known quantity is a very strong presence,” wrote Margaret Atwood in

Negotiating with the Dead

, “as the Victorians realised about sex.”

“Don't get kidnapped,” said my mother, whenever I left the house. “Don't get abducted. Don't get raped and murdered.”

“I'm only going to the shop,” I said, or later, over the phone from London, “to the office/Manchester/the loo.”

“So?” she said. “They have murderers in Manchester, don't they?”

About once a week, she rang after a sleepless night and we went through the routine.

“I had a sleepless night.”

“What?”

“Someone broke into the house in the night and snatched you away.”

Or:

“Someone ran away with you on your way home from work.”

Or, simply:

“Your dirty washing.” The more ludicrous the cause, the better. Once, a personal best, a sleepless night about my flatmate's dirty washing. I told him by way of a boast, “Look how much my mother loves me, so much she loses sleep over whether

you

have clean clothes or not.” I remember he giggled rather nervously.

Only occasionally her comic tone faltered. In the car on the way back from Oxford one day: “Don't be cross with meâI had a sleepless night.”

I was instantly furious. “For God's sake,” I said. “It was one date. ONE DATE.”

My mother looked at me ruefully. “I thought he might cut you up and put you under the floorboards.” This referred to a recent case in the news in which a man from Oxford had murdered his girlfriend and, folding her like a ventriloquist's doll, stuffed her in a suitcase under his bed. The floorboards part was a flourish I think she got from Jack the Ripper.

“I'm not going to tell you anything if this is how you behave.”

Her contrition evaporated. A warning look. “People get abducted, don't they? People get murdered.” And there it was in the car with us, the huge mauve silence at the edge of the known world. “These things happen.”

“Not to me, they don't.”

She looked at me then with every ounce of love in her system.

“No, not to you.”

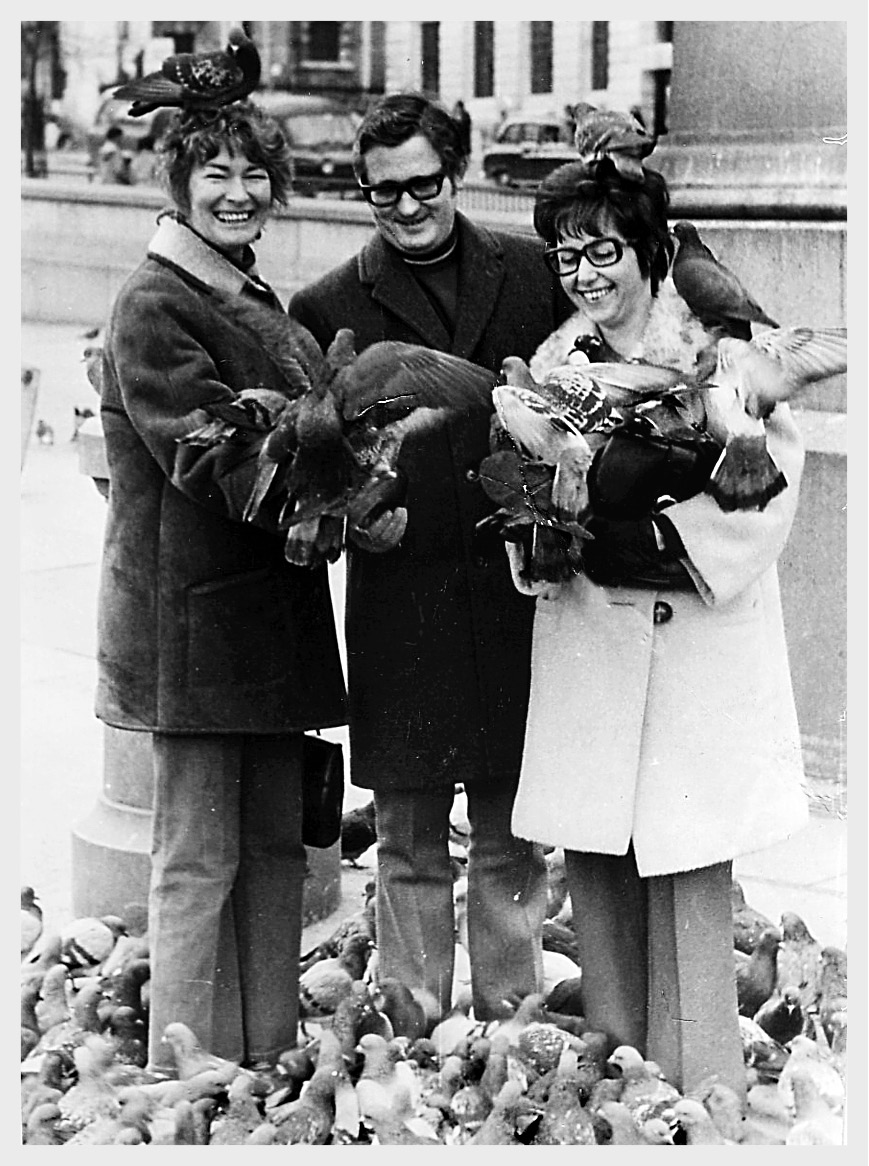

Mum, her sister Fay (in the huge hipster glasses) and Fay's ex-husband, Frank, in Trafalgar Square before I was born.