She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me (12 page)

Read She Left Me the Gun: My Mother's Life Before Me Online

Authors: Emma Brockes

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Adult, #Biography

“Nasty business,” said Reg.

There was a suggestion that my mother had been interested in Denise's brother, a doctor, and despite being the “other daughter,” I sensed from a throwaway remark that the interest had been discouraged. In any case, when they were all in their mid-twenties, Joan married Danny and Denise married Reg. My mother didn't marry for another fifteen years. Her emigration, I had always thought, was a mixture of ambition and flight from disaster, but it seemed to me now there were other reasons, too. Sitting in her living room in Cape Town, Denise recalls my mother congratulating her on the engagement and saying sadly, “Everything is going to change.”

“And I said to her, âNo!'” says Denise, tears spilling down her cheeks. “We'll be friends like we've always been. But we moved out of town and had the boys, and it never was the same. She was right.”

It was Denise who wrote to my mother, “More and more as the years go by I see that friends are jewels . . .”

There was, I think, an element of pride in my mother's defection from her peer group. Her disinclination to marry must have felt like a failing. If she left, she could buy herself time. She could slip her generational bindings. She could do as she pleased and, win or lose, write home insisting she was having the best time in the world.

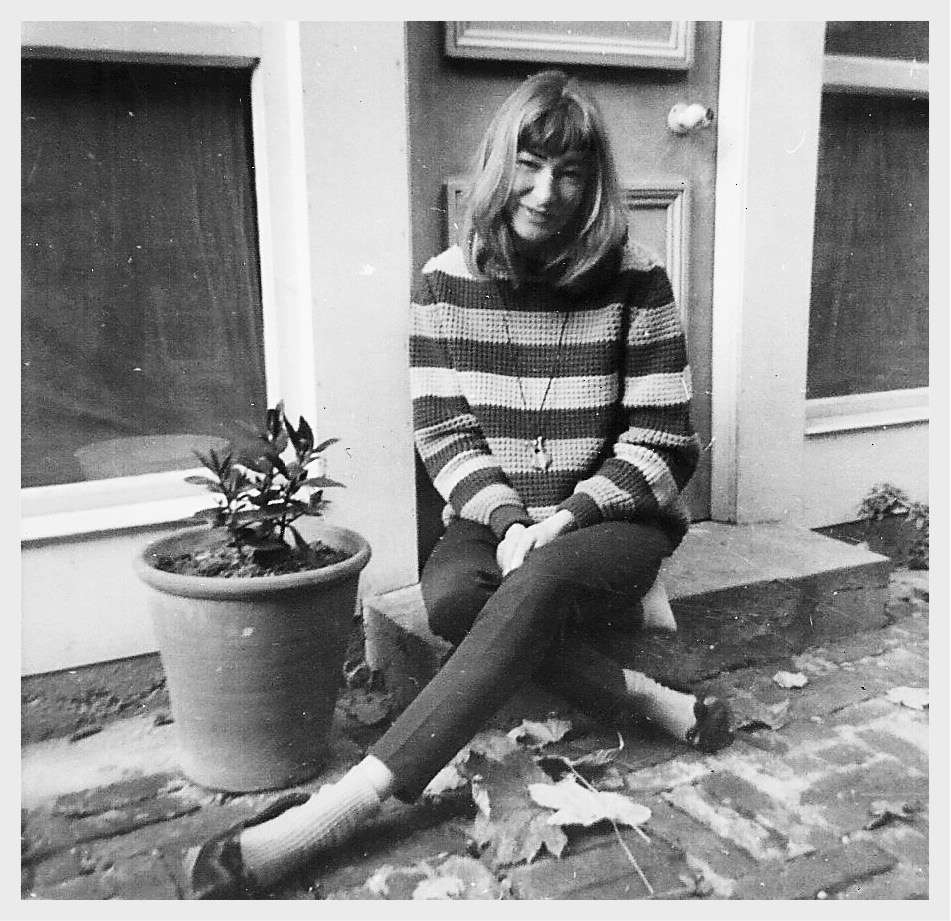

Figuring out how to be: Mum in England, in the 1960s.

Gold Jewelry

SHE CAME TO LONDON

knowing no one, clutching a single letter of introduction and a sheaf of references going back to her first job at sixteen. I found them after her death, stashed in the secret drawer. There was something terribly poignant about those papers. My mother had told the story of going to see

Dracula

at the cinema in Johannesburg and being so scared that, when she got home, she put bulbs of garlic around her bed before going to sleep that night. Hanging on to those references for forty years struck me as a similar gesture.

Unterhalter's Mattress Works had found her “well above average” and expressed regret that their merger with the Edblo Bed Group had forced them to let her go. The

South African Mining Journal

recorded her cheerfulness and refusal to take a single day's sick leave in a year's service. Wolpert and Abrahams went so far as to say that as well as being neat and conscientious, she had “a very pleasant personality.”

The letter of introduction was from the head of the law firm. Mr. Natie Werksman, of Werksman, Hyman, Barnett and Partners, who wrote to his friend, Mr. John Craven, Esq., of the Anglo-African Shipping Company Ltd., sending his kindest regards to Mary and alerting his friend to the arrival on his shores of his strongest bookkeeper, whom he would consider it a favor if Mr. Craven would assist. Two months later, Mr. Craven sent a telegram from his office on Mincing Lane, London, to a temporary address at the Overseas Visitors Club. He thanked the young lady for her letter of December 12. He sympathized with her predicament, but regretted he could offer no solution beyond suggesting she share a flat with a friend, as so many young people seemed to be doing in those days. “It is,” he added, “very thoughtful of you to let me know how you are getting on.”

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

THE COMPANY THAT

was so important to my mother was founded in 1917 by Natie Werksman, and by the time my mother joined in 1956 it was a booming practice on Johannesburg's Commissioner Street. Most of the staff were Jewish and, before she corrected them, assumed that she had Anglicizedâor rather, Dutchifiedâher name from Dekowitz to DeKiewit; it stuck as a nickname and she carried it with her to London and beyond. When my dad teasingly used it, it had always made her smile.

These days, like most blue-chip firms, Werksman's has moved out of the city center to the suburbs. The old colleague of my mother's I had e-mailed from England had met me in the foyer there a day or so earlier and we had gone for lunch. As advertised, Alick was charming and energetic, with a friendly mustache and twinkly eyes. He was a little bemused by the meeting, but game and tremendously cheerful.

“I was a lowly clerk!” he said, as we ate shrimp and drank fizzy water in the sun. “And a clerk in those days was like a salt miner! We were nobodies! I remember Pauline was always very generous. We couldn't believe she actually talked to us!”

He was the political one. He once visited Bram Fischer, the great antiapartheid lawyer and activist who died in jail, and the day after got a call from the security forces, warning him off. He waited table at a function for eminent lawyers, where Joe Slovo stood up and addressed the room. Slovo, as head of the South African Communist Party and, eventually, the only white man in Nelson Mandela's cabinet, was a familiar personality in our house. He was a great hero of my mother's, as was Ruth First, his wife. “Jews,” said Slovo, “I'm disappointed in you. Compassion is one of the staples of our religion and you've put making money first.” Everyone laughed and shouted, “Show us your red socks, Jo!” When Alick nervously poured him some wine, the great man said kindly, “You must be a clerk, bloody useless at everything.”

I asked Alick if he remembered a Sima Sosnovik. “Yes! Sima. In accounts. Very formidable.”

“My mother looked up to her a great deal.”

“Your mother was formidable, too,” he said.

I poured more water and picked at my shrimp. “Were you aware of her being involved in any trouble at all?”

“What kind of trouble?”

“She was involved in a court case.”

“No.” Alick lifted his eyebrows. “I don't remember anything of that nature.” There was an uncomfortable pause. “What was it about?”

I hesitated. “Domestic trouble.” I couldn't believe myself. I sounded like a bad public-information broadcast.

“No,” said Alick, and as with Joan, I sensed a subtle but distinct closing of generational ranks.

“The prosecutor's name was Britz.”

“Afrikaans,” he said. He didn't know a Britz but suggested I check with the Department of Justice.

There was a pause. Alick looked at me expectantly.

“I went to the National Archives in Pretoria to find the transcript,” I said, “but there was only stuff for the first trial. Nothing for the second.”

“Was the verdict at the High Court not guilty?” says Alick.

“Yes.”

“Well, that's why.”

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

I CAN'T IMAGINE HOW

lonely that first year must have been, or what internal reckoning went on as my mother tried to rebuild herself. I imagine her a little like the Enigma machine, ticking over for months and years, trying every possible mathematical combination until she cracked a way to live. When I finally came to interview her friends from that era, they depicted her as someone who was very obviously crushedâ“Compressed,” said one, “but not

de

pressed”âbut managing. Typically, her own summary of herself in that period was “I was shy and it was holding me back so one day I decided not to be.”

After the week's accommodation in the hostel expired, she and some Australian nurses she'd befriended on the boat moved into a suite of bedsits. My mother's was on the top floor. When she became ill with flu that winter, they took turns, after their shifts, to run up and down the stairs with soup and oranges.

She moved again, this time to a rooming house in west London, where she met Bob, who would become a great friend and provide her with one of her favorite stories from that era. A few years later, my mother was at a dinner party at Bob and his partner Nick's flat, carrying plates through a narrow corridor from the dining room to the kitchen when she tripped on the step, smashing the plates and cutting her own throat. They rushed her around the corner to Charing Cross Hospital, where she was stitched upâthe surgeon told her she had missed her jugular by a hairbreadthâand she returned to the flat, where she insisted that everyone finish the dinner party.

She found a receptionist job at a private members' club in Berkeley Square, then in a doctor's surgery, and then at the law offices where she met my dad. When I was a few years old, she decided to go back to work part-time, and found a job two towns over as a bookkeeper in a jewelry store.

It was a slightly larger town than our own, and I liked to go there with her in the school holidays, to walk around the shops, buy pens from the stationer's, and look in at the pet store. She would give me a pound, and I would go to the bakery and buy a sausage roll for lunch. Sometimes, after she finished work, we got our hair cut at a place called Antoine's.

The jewelry store was in a row of shops next to a florist's and a dressmaker's. My mother's desk was at the back, in a windowless cubbyhole one step up from the open-plan room where the other bookkeeper worked. While she hammered at the adding machine, I sat on a three-legged stool by her side and tried to make words on the calculator.

It was a point of pride for my mother never to go on the shop floor; she entered through the garage and via a side doorâthe stage door, as she probably thought of itâand during tea breaks came out from the cubbyhole to socialize with colleagues.

There was Jackie, the sales assistant, who dyed her hair a deep shade of red, which my mother called burgundy and disapproved of. There was Only Eileen. (“Hello, dear, it's only Eileen,” said Only Eileen to her husband, Arthur, whom everyone knew to be unemployed and available during the day for pointless phone calls. Her titter would carry through the partition and make my mother pause at the adding machine.) And there was Ron, who owned the shop. He could usually be found at his desk, head bent over a dismantled watch, knees grazing the improvised weapon he kept under his desk. In thirty years in the jewelry trade he had never had the opportunity to use it. When Ron said, “We've never had an intruder,” the wistfulness in his tone was unmistakable.

I loved hanging out there. I loved going onto the shop floorâspecifically, I loved the transition from the back of the store to the front. My mother told me not to make a nuisance of myself and to limit my trips to a couple per shift. I tried to make them last. While everything out back was gray and held together by staples, out front it was hot and red and gold, like a royal box at the theater. It sizzled with light. I loved looking at the heavy chain-link necklaces nestling on red velvet; plump ring trays with diamond rings and semiprecious birthstones; antique silver, turning black from the base up like a creeping blush. Ron's wife, Connie, would tell me to choose something from a revolving glass carousel to take home. I chose a solid-silver squirrel, about three inches high. As I passed Ron, he winked and said to me, “Terrible woman, my wife.”

It was a large part of my mother's life, this work, and she enjoyed it. She enjoyed her skirmishes with Ron, who, she said, needed taking down a peg or two. He had a friend, Bill, a mechanic who timed his daily appearances to coincide with the tea break, and my mother fought with him, too. “I like a good ding-dong,” she said. My mother had no time for Bill, but she didn't like the way Ron treated him; it struck her as bullying. “He is obeast,” said Ron nastily of his friend one day.

“Yes,” she said, “he certainly is

obeast

, it must be terrible to be

obeast

like that. People who are

obeast

must

have the most difficult time. Aren't you glad you're not

obeast

, Ron?”

It was clear to Ron my mother was laboring a point of some kind. The following day, he observed casually, “Terrible thing, to be obese.”

Ron was an enthusiastic supporter of Mrs. Thatcher, who, he said, was “keeping Britain for the British.”

“Ronald, you are a total fascist,” said my mother, and they both looked delighted.

When my mother related these exchanges to my father, he said irritably, “Why don't you leave? You don't have to work.”

“I suppose the job suits me,” she said. “I am the only one who stands up to him!”

She had an idea of herself, in relation to Ron and the others, as outré, someone who could bandy about the word “fascist,” as well as “transvestite” and “egomaniac,” and have a large as well as a small sense of what they meant; someone for whom it was weird to the point of parody to be working among these kooks in a dark cubbyhole in the sticks. That's why Jackie's burgundy hair annoyed her, I think; it was a rival critique.

It was true what she said to my father: the job did suit her. She loved the balanced account book, the neat row of columns. Ron was in awe of her perfectionism. He might, if he'd been the introspective type, have been surprised that anyone should take such pains over the work they did for him. Now and then they went on valuations together, to big country houses where the valuables were laid out on the dining-room table for Ron to examine. These had the tenor of day trips, and my mother always returned from them in high spirits. Ron was impressive, then; focused, looking through his eyeglass at the hallmark on an eggcup, revealing as fake what was thought to be priceless. At these times she felt proud to be part of it, proud of his expertise. She said Ron could have been an engineer if he'd put his mind to it and hadn't been such a fascist.

Over the years, my mother collected a lot of nice pieces from the shop, “my jewels,” as she called them. She was particularly fond of goldâof old gold. It is a widely held view among jewelers that the only good gold is old gold. (There is a commensurate view, that all old gold is stolen gold, but that's another matter.) New gold has a blank, childish look to it and is too yellow, like cheap margarine. Old gold is greenish. The gold in our house was taken seriously, insured with typed-up valuations, elaborately hidden from burglars in those improvised safes, along with her other jewels. Garlic around the bed comes in many different forms.

She ended up working there for nineteen years. When she retired from the shop, Ron made her a clock, with the twelve letters of her name where the numerals 1â12 should be. “I'm terribly fond of him,” she said, “in spite of everything.”

â¢Â   â¢Â   â¢

AFTER SHE STOPPED WORKING,

my mother's energy levels seemed to droop. She tried to learn bridge, but it didn't take. She switched from yoga in the village hall to pilates. She talked with great enthusiasm about the teacher, whom she sponsored to run the London marathon. She sat for hours by the window, looking out at the trees, drinking cider or ginger wine and shining ever so slightly, the way people do when they're a bit off-kilter, a few drinks in or at that point of exhaustion when, just before the final collapse, their back-up generator kicks in and for a short while they shine, so it seems, at a cellular level.

When the condolence letters came in, I hadn't thought of Ron for years. Writing wasn't his medium; my mother always mocked his poor spelling. He wrote, “Paula was such a strong woman in body and mindâshe was, I always felt, indestructible. Everything she ever did for us was always just so and it used to give her great satisfaction to find an error of one penny!! We had many laughs together and some very interesting conversations about British colonial policy. After Paula retired I continued to use the office but it was miserable without her and I soon ceased to use it.” Of all the letters we received, Ron's was the one that made me burst into tears. It struck me as the truest dedication, a tribute to her strength and humour, but also to her idea of a job well done: precision, order, a stand against the chaos.