Shame of Man (50 page)

Authors: Piers Anthony

CHAPTER 17

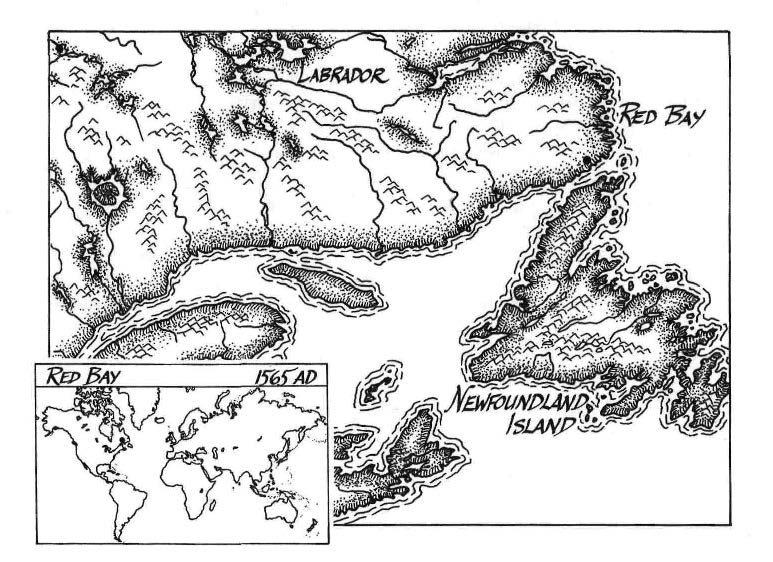

TERRANOVA

The Basques are one of the very few peoples of Europe to have escaped the Indo-European linguistic conquest; their language does not relate to the others. This may have been because they were fierce mountain folk in the Pyrenees, in northern Iberia (Spain), hard to get at, and very protective of their culture. What is not well known is that they also went to sea. Soon after the European discovery of the New World, Basque whaling ships were operating there. The life and work were hard, but the pay was good, and they were up to it. They went to a fishing port they called Butus, in Terranova, which today is known as Red Bay

in the New World, on the Canadian coast just north of the island of Newfoundland. There they caught and processed several thousand whales.There is no evidence that women or children were on these voyages. But perhaps there could have been a special situation, in 1565.

I

T was infernally smelly near the tryworks, but the heat of its operation was a comfort in the chill of early winter. Besides, Ana used its fire to cook with. So they endured it. They knew it would not be much longer, because the

San Juan

had a full cargo of whale oil and was ready to sail for home. Tomorrow they would board it, and the following day be on their way.

The tryworks was a firebox set into the ground, facing the island beach. It was a square hole lined with stone, four feet across and just about as deep, to hold the big steady fire needed for the rending of the oil from the blubber. Wooden posts supported its red tiled roof. It was a constant job to find and haul dry wood to keep several tryworks going all day. But without this stage, the whalers would not be able to function, because the blubber would not give up its oil before it spoiled. So the tryworks was really the center of the operation.

“Father! A boat!” Scevor cried, pointing.

Hue looked. A

chalupa

was rowing toward them: one of the fast whale pursuit boats from the ship. But instead of a harpooner, this one had a lesser officer. Hue recognized him by his heavy blue woolen trousers gathered at the knees and his red long-sleeved shirt. The craft landed, and the officer stepped out and approached Hue. “Bad news,” he said. “The men voted to exclude you. They don't want women back on board.”

“But we came here on the

San Juan!”

Hue protested. “We paid for the privilege. You can't just leave us here to die.”

The man shook his head. “This is not my choice, my friend. I am only reporting on their decision. They say that they were not consulted about the matter when you boarded, and that we had bad luck on the trip because of you. Two women and two of the sinister hand—please understand, they are frightened. It is not a personal thing. They refuse to risk it again. But we are not stranding you. There is another ship. We are refunding your money. Give it to Captain Ittai.” He handed Hue several silver coins.

“Who may be just as superstitious,” Hue said tersely. But he knew they would have to try it, because it was clear that they would not have a compatible berth aboard the

San Juan.

“They may be unduly credulous,” the officer agreed. “It is the way of seamen. But I understand that Captain Ittai is not, and he will take you.” He turned smartly about and marched back to his boat.

Hue and Scevor returned to their temporary sod house. It had red roof tiles which had been brought across as ballast for the empty ship. The Basques were nothing if not practical. They had made their oil barrels from

staves on the way across. Nothing was wasted, not even time. So even their ballast had definite uses elsewhere.

“They won't take us?” Ana asked incredulously. “But we paid, and we've been working,

and

entertaining them!”

“They gave back the money. They're afraid. Of women and hands. But they say that we can go on the

San Pedro.”

“We'll die if we don't,” she said grimly.

Hue went back to work tending the cooling tub. This was the last stage in preparing the whale oil before it was barreled. The tub was made from a barrel sawn in half and partly filled with water. The hot oil from the tryworks was poured in, and cooled by the cold air and water. The oil quickly coalesced and floated on the water, and the impurities floated on the oil, where Hue sieved them out during the cooling. When the oil was clear and cool, he dipped it out carefully and poured it into a complete barrel. When he had several barrels, a boat would take them out to the ship. Making oil was a far cry from making music, but it was gainful work, and he didn't mind it any more than Ana minded cooking pots of cod and beans for the men to eat. It was part of the deal.

The deal was that they had paid to come as a family unit on this nonfamily business venture. It was highly irregular, but necessary for them, because they had had to flee Spain and get out of reach of the king, and the power of Spain was such that this desperate ploy was the only feasible way. The Basques had never liked being dominated by Spain, so had had some sympathy, but couldn't protect them. Instead they had signed them as crew members aboard the whaler

San Juan,

and the ship had then set sail for Terranova, one of the few regions of the world that the Spanish king could not conveniently reach.

The money had done no more than gain them the right to be on the ship; they had to haul their weight, as every crewman did. So Hue and Scevor had assisted the cooper on the voyage across, assembling hundreds of oil barrels from pre-fitted beech and oak staves. They used hoops of green alder to make the casks tight. Hue's musician fingers turned out to be similarly dextrous, not sinister, with the staves, and even five-year-old Scevor had a touch in matching stave to stave. Ana and Min had settled in as cook's assistants, and though the cook was reputed to be the grouchiest man aboard, he soon had to concede that they were good at it.

But there was one more aspect to the deal. They agreed to entertain the crew, in exchange for being left alone by the crew. In slow times they did music and dance performances on the deck, and the captain issued a standing order that any man who touched any of them, literally, would be keelhauled. He was a man of word and discipline, so the threat was meaningful. That meant that the men could look all they wanted, and say what they wished, but not one finger touched woman or child. The order was necessary because not all the men were married, and not all the

married ones were faithful, and some had pederastic tastes. But all of them were tough, whether as workers or fighters or simply enduring the rigors of the weather. Thus the suggestive dances of the women were roundly applauded, and the boy at times became a dancer too, but all were off limits. It had worked reasonably well, but toward the end of the cruise across the big ocean there had been increasing grumbling and intensifying hunger in a number of eyes, and the officers had had to use the whip on occasion to maintain discipline.

So perhaps it wasn't surprising that the balance had shifted, and now the family was not welcome aboard the

San Juan.

Hue knew it was not a complete change, for there had always been a sizable minority that objected to their presence, and now there was surely a sizable minority that preferred their presence. Probably the captain had made the decision, for the sake of continuing discipline, not caring to risk even the slightest chance of mutiny.

However, the men of the

San Pedro

were fresher from Spain, so not as hungry for women, and Captain Ittai had a less harsh yet somehow more effective mode of discipline. So it did seem to be time to change ships. But Hue had a nagging tinge of uncertainty, because the

San Pedro

had already been unlucky, and might decline to risk any more of the same.

“There she blows!” the lookout on high ground cried. Hue looked, and saw the signs of one or more bowheads. Immediately men boiled out of their temporary shelters on the island and piled into their chase boats. Each

chalupa

had places for seven: four rowers, a helmsman, a harpooner, and the boat captain. They slipped through the icy water with astonishing speed, angling out to intercept the whales that were swimming near the land. One boat was too far to the side to catch a whale, but the other cut in immediately behind a whale, maneuvering to avoid the dangerous flukes. Its harpooner hurled his barb and scored on the whale's back. Then the men cast the drogue snake over the bow and hung on as the harpoon line went taut.

Now it was time for endurance, as the injured whale tugged the craft rapidly across the water, sometimes cutting back to charge the boat, sometimes diving deep, trying to escape the pain. This stage could last for hours, as the whale slowly tired, and became vulnerable to a stroke to a vital organ. Once it was dead it would be laboriously towed to a trying station on the shore. Then the flippers and tail would be cut away to facilitate rotation of the carcass, and three men would stand on top of it, cutting away long strips of blubber. They would cast these ashore, where a man covered with soot and fat would shovel lumps of blubber into a boiling cauldron. The boiling removed the oil, and fritters of exhausted blubber would be fished out. Then the hot oil would be poured into the cooling barrel that Hue was tending. The process was messy, stinky, but efficient.

In a few more days the

San

Pedro

would have enough oil to return to Spain, though far short of a full load. The ship had suffered a series of misfortunes, losing a number of good men and a boat, and a mishap had caused a fair proportion of the casks of oil to be contaminated. That was why the ship was staying until the end of the season, when the very last whales passed, trying to make up the difference. It would not be a complete loss, because the ships worked for the same employer, and the incomplete cargo would be mitigated by the full cargo of the

San Juan.

Still, it was not a happy time.

There was a noise farther along the shore, and a cry. A cauldron had burst, dumping its valuable oil into the firepit, not only being lost but effectively destroying the tryworks. More bad luck.

Then another boat came from a ship, this one from the

San Pedro.

"This will be news from Captain Ittai,” Hue said.

“Will he take us?” Scevor asked, concerned.

“Of course he will,” Hue said. Because there was no alternative; it would be a death sentence for any people left here for the winter. The water was close to freezing already, and huge icebergs could be seen sometimes in the sea; it would be much worse in winter.

The boat arrived, and its passenger got out and approached Hue. It was Captain Ittai himself. “We have considered the matter, and we will take you,” the man said. “Our luck couldn't be much worse than it has already been. But some of the men are against it. So I have suggested this challenge: board the ship now, and if our luck turns, we will assume that your influence is beneficial, and the matter will be at rest.”

“And if your luck turns worse?” Hue asked.

“Then the naysayers win their bets, and will be satisfied. You will not be left here.” He proffered his hand, and Hue took it. Captain Ittai had found a way to secure their passage, regardless.

Hue and Scevor went to tell Ana and Min. “We will be aboard the

San Pedro

tonight,” he said, and explained why.

“I will feel safer there,” Ana said, flashing him a weary smile. It was a bit more comfortable on land than on a ship, but now that there was a question about their return to Spain, the ship was attractive.

They finished their shifts at the tryworks and cooling tub, and got into the captain's boat. There were only two oarsmen now, because this was not a whale chase, leaving room for them.

They boarded the ship and went to the allocated cabin. And the mischief started. There was a shout from the tallest of the three masts: “Storm ahoy!”

That was the last thing they wanted. There was little a ship could do in a storm except try to ride it out, and it was not a pleasant ride. Those camping on land would be better off. At least they wouldn't have to endure

the embarrassing threat of seasickness from the violent heaving on the waves.

Hue saw the crewmen looking at him. He knew they were regretting the presence of the family on the ship, taking the sudden storm as an omen. He hoped that their concern did not prove justified.

But Min caught his glance with her large eyes. “The spirits of the air are not against us,” she murmured.

That reassured him. She had never yet been wrong about the spirits.

“But the spirits of the whales don't like the ships,” she continued.

“That is hardly surprising.” Hue found the slaughter unpleasant, but did not feel it was appropriate for him to object to the business of the ships that had given his family sanctuary.

The storm moved swiftly in, as if it had come into being with the sole object of striking at them. Dark clouds piled up from the horizon, blotting out much of the light of day. The crewmen scurried about the ship, tying everything down, especially the sails. They were going to ride it out at anchor, to prevent being blown onto the rocks of the shore. Storms were especially dangerous to ships near land.