Shame of Man (48 page)

Authors: Piers Anthony

“What is this?” Baa demanded.

“You took my child,” she replied, staring him down.

And that was it. He had taken her child, to make her available for this, and she had instead turned her new husband against him. The man had done her bidding. She had lost what she most valued, so she had denied her brother what

he

most desired. There was nothing he could do about it.

Baa stalked away. Now everyone knew how his ploy had failed. He had sought callously to use his sister's child for his own advancement, and paid a price. He had lost not only the position, but his reputation, for Scil had made a fool of him.

Yet Huu knew that she could almost as readily have made a fool of Huu himself, and cost him dearly, had her anger been directed at him or his family. She had gone to his home. Had she taken a knife to Aan—

He aborted that thought. Scil's anger could justifiably have been directed against him, because he had made the deal with her brother. But he had in effect offered what no one else could: a loving family for the child. That was what had saved him. Because Scil did love her son.

Was Easter Island colonized from South America? Legends of both the island and the continent can be interpreted to suggest that this was the case, and the presence of cultivated South American plants such as the sweet potato, the bottle gourd, the manioc, and the totora reeds from which they made their boats confirms that some contact occurred. There was also the giant palm, which grows on the coast of Chile and nowhere else

—

except Easter Island, before it and the other trees were destroyed by man there. One of those giant trunks seems to have been used as an anchoring post for ropes, to prevent statues from sliding down the slope from the quarry too rapidly. The presence of a written language, as yet undeciphered, in the island also suggests an origin on the continent, where legend speaks of a similar lost script. The appearance and blood group of the long ears may also associate with South America. There are representations of sailing craft, and one type of house emulated those same ships.But there was also colonization from the Polynesian islands, because their racial type is also present, as the short ears. They brought bananas and chickens, but not much of their culture. One legend indicates that they served as slaves for two hundred years, then revolted and largely destroyed the long-ear power. At that point all work on the statues stopped, leaving hundreds still in the quarry. The subsequent island history was violent, with constant warfare decimating the population, and all the standing statues were eventually toppled. Later still slave ships abducted many islanders, and when some slaves were returned, they brought smallpox, which wiped out most of the rest. Catholic missionaries sought to stamp out all pagan evidences, so that invaluable wood carvings and tablets with writing were destroyed, leaving no one able to read those few that were salvaged. Could Polynesian origins account for all of the original colonization

and culture of the island, except for chance vegetation carried by birds or sea currents?Today Easter Island is faring better, as a tourist attraction, with many of the statues restored. But the debate continues whether there was any non-Polynesian colonization. What, for example, accounts for its lack of pottery, as there is a strong ceramic tradition in South America? What about its lack of sophisticated textiles of the type found on the continent? There was clay on the island for pottery, and fibers for textiles. Would they have brought sophisticated stoneworking technology, without similarly useful ceramics and weaving?

The picture on the west coast of South America is just as confused. Circa A.D. 1100 was between empires, and references seem to contradict each other. So it was difficult to establish exactly who was where, and harder to judge who might have sent the second mission to Easter Island. There isn't any credible historical evidence for such voyages. Yet there is similar statuary, and legends did correctly identify the location of Easter Island, suggesting that ships had not only gone there, but had returned, despite adverse currents. But there are Polynesian legends too, and certainly the ancient Polynesians had the sea traveling expertise to reach Easter Island.

What of the white-skinned, goateed, red-haired folk who became the long ears of the island? Continental legends have them arriving by reed boats from the north, bringing civilization with them. They taught the natives how to do things, then sailed away into the Pacific. Can this be believed? If so, where did they come from? Conjectures abound, but can become wild, such as tracing a group from Mesopotamia around Africa to Central America, across Panama, and down the coast, bringing their reed boat and stone carving technology with them. Yet part of the reason the Inca Empire fell was that the Incas took the Spaniards for these returning god figures. White skins and red hair don't generate in the tropics. Perhaps tissue typing will offer insights, in due course. Preliminary results suggest that the type is Basque, which may indicate that the legends of white men with ships stemmed from recent experience. Certainly the Basques ranged the Pacific in the sixteenth century, and if contacts with them were attributed to earlier times, that might be the explanation. The mysterious pictographic writing might also be a more recent invention, emulating the European scripts. Even the manner the statues were moved is in question; Thor Heyerdahl demonstrated that they could have been walked, but that may have been only for short distances, because the volcanic tuff wore down rapidly. They may have been hauled most of the distance on sledges, or even on tracks and rollers. And the red headstones and inset eyes may have been later innovations, not used at the time of this setting. So every part of it can be questioned, and the background of the settings seem to be cobbled together with spit and

string, but the essence is intact: impressive works were accomplished by supposed primitives.Overall, the mystery remains, with the apostles of the various theories

seemingly more interested in supporting their chosen sides and discrediting rivals’ claims than in the truth. But there is one lesson to be learned from Easter Island, regardless: a habitat with limited resources may not be wastefully exploited indefinitely, lest disaster strike. There will be more on that in the Author's Note.

CHAPTER 16

MISTAKE

In

A.D.

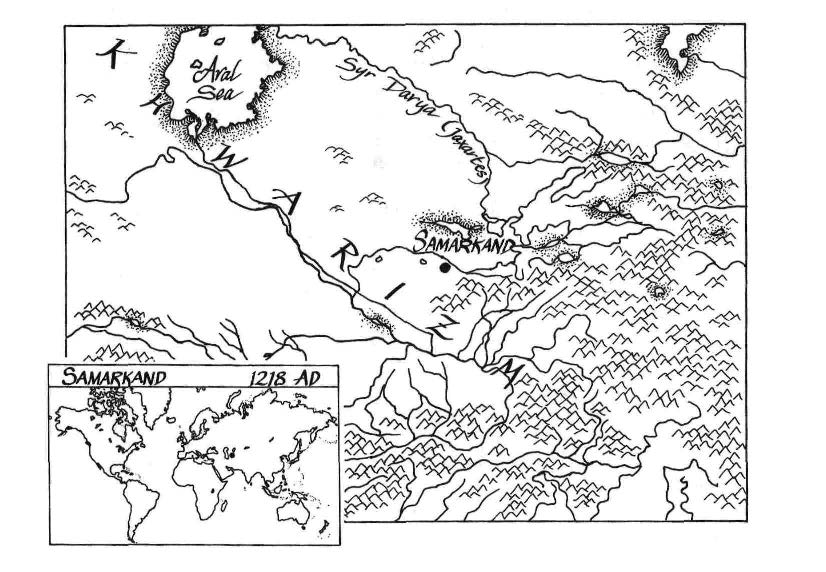

1218 in central Asia, east of the Aral Sea, the region of Transoxania ("land across the Oxus” River, later the Amu Darya River) was the border between two rapidly growing empires. To the west was Kwarizm, a Moslem state; to the east, Mongolia, a shamanistic culture that viewed the great religions of the world with tolerance as long as they presented no political threat. The Shah of Kwarizm, Muhammad, had largely consolidated his holdings; the khan of Mongolia, Genghis, was then in the process of conquering China, and preferred not to seek further quarrels elsewhere at the moment. The khan made a point of learning about the countries beyond his borders, and knew that Kwarizm

was larger and richer than Mongolia, and could mobilize larger armies in this region, because of Mongolia's diversion to the east. Prudence seemed best. So he proposed that there be peace, with the river Jaxartes (later called the Syr Darya) as the boundary between them. He sent envoys with rich gifts to the Shah, with the friendly message that the khan would look upon the Shah as his son

—

that is, fondly.Unfortunately, there was a slight misunderstanding that led to complications.

T

RY this, Scevo,” Huu said, setting the instrument down before his four-year-old son. “You are good on drums; this is better.”

“A dulcimer!” Miin exclaimed, delighted. “Where did you get it, Father?”

“There was a barbarian at the bazaar who did not know its value,” Huu said. “It was so cheap I had to have it.”

“He probably got it from plunder,” Ana said ominously.

“Don't be concerned; I wiped the blood off it.”

Ana gave him a dark look and returned to the kitchen section, where she and the servant girl were preparing the afternoon meal. She was probably right; when rare quality artifacts appeared in the bazaar, they often derived from plunder. Soldiers and cavalrymen snatched whatever looked interesting, then dumped it for what prices they could get. The merchants cheated them shamelessly, but perhaps it was only fair, as they had probably killed the prior owners. The spoils of war were the main reason to join a military force, and lucky and unscrupulous mercenaries could do very well for themselves, if they survived. But Huu could not blame Ana for disliking this aspect.

“Where are the sticks?” Miin asked.

“He must have lost them,” Huu said. “A barbarian wouldn't even recognize this as a musical instrument. I'll make a set.” He got to work, quickly carving two fine wood beaters. Such was the force of habit that he looked warily around before starting the carving, and then faced a wall while doing it, so as to conceal the use of his left hand for the knife. His family knew all about his bad-handedness, of course, but he could never afford to forget the way outsiders saw it. In public his right hand was dominant.

Then Miin demonstrated them for the boy. “One in each hand, like this, and strike single strings, lightly, so.” She struck a string, and a fine note came forth, augmented by the soundbox built into the base of the dulcimer.

Scevo's face widened into a huge smile. He took the sticks and beat on two strings, making two notes. He liked banging on things, especially when the things made interesting sounds. He beat on two more, making two new notes, and then two more. His happiness radiated in time with the sounds. This was a good instrument, because the child's own bad-handedness did not show; it was always played with both hands.

“Like this,” Huu said after a moment. He sat behind the boy, reached around him, took the two little hands in his, and caused him to beat two notes alternately, making a primitive tune. Then he beat them together, making a primitive chord. “Can you do that?” he asked, letting go.

Scevo beat alternate notes, then chords. He was completely delighted.

“Now I will join you,” Huu said, bringing out his double clarinet. “You play those notes; I'll play the melody.”

The boy joyfully played the notes, and Huu went into a suitable melody. It worked well, for Scevo had good timing, and Huu had long experience that enabled him to adapt to almost any accompaniment.

“I think we have found his instrument,” Ana remarked, relenting in her reservation toward it.

After a moment, Miin stepped out before them, dancing. At age eleven she was emerging as a beautiful girl with fine legs, her slenderness making her nascent breasts seem more. She swirled her long dark hair around and moved her hips lithely. Huu watched with appreciation tinged with concern; she was almost too lovely, which could put her at risk in another way. Her hands were normal, but there was a demand for loveliness for the harems of the wealthy or powerful, and some men did not take no as a suitable response.

Then Ana joined them too, moving her own mature body in the practiced ways of the experienced dancer. The two made a marvelous set, the woman and the girl, matching step for step. Huu elaborated his theme, and Scevo maintained the beat. The boy definitely had a talent for it; he had not missed a note, after getting it straight.

Huu completed his melody, and stopped, and Scevo stopped with him, aware of the patterning of it. “I think we have a family group,” Huu said. “A troupe.”

“I think we do,” Ana agreed. “Now it is time to eat.”

They went to the table, and the servant served them. Desert Flower was a girl of the steppes who worked for them to pay off a debt her family had incurred. She was thirteen, a pretty young woman in her own right, and very competent and loyal. In a few more months her service would be done, the debt paid. Then she could either go home, or continue service for pay. Huu hoped she would choose to continue service, because she got along well with Miin, was helpful with Scevo, and was always pleasant. She would surely marry well, in due course.

There was a sound outside, as they were finishing their meal, and a firm knock on the door. Huu went to meet the messenger from the palace who stood there. “Summons from the palace for service,” the man said gruffly. “Music, dancing, within the hour.”

“We will attend,” Huu said. There was no other response he could make. He had done well in Samarkand, because of the favor of the palace; the nobles of Kwarizm liked his music and Ana's dancing. But he had to attend

whenever called, day or night. The palace messenger would conduct them. This was nominally an honor guard, but also assurance that they would not delay.

“Hurry,” the messenger said, not relaxing.

Huu re-entered the house. “Song and dance at the palace,” he said. “We must both go immediately.”

“We will all be there,” Miin said, donning her veil. “Scevo too.”

Huu looked at her, then at Ana, who shrugged as she veiled herself. The children had been close, ever since the adoption of Scevo, and the boy definitely preferred to be near his sister. Desert Flower could have taken care of the child during their absence, but it was now possible to claim him as a musician. It would be a novelty that might be appreciated at the palace. Appreciation could bring rich rewards.

So they took the children, with due cautions about remaining in sight of their parents, and silent. Desert Flower would keep the house in order alone.

They set out on foot through the city of Samarkand, Ana and Miin remaining fully cloaked and veiled in the fashion required of Moslem women. Huu wore the turban and distinctive robe of favored entertainer, which should have protected him from molestation on the street, but the

messenger's sword was also clearly visible.

There was the sound of the horn: it was dusk, time for worship. All

around them the people were facing toward Mecca and prostrating themselves on the ground. The four of them and the guard did likewise. Then they got up and resumed their travel, and so did everyone else, just as if nothing had happened.

There had been new construction recently, since the Shah moved his capital here. The smaller stucco buildings were being razed to make way for the grandiose structures of governance. But all of them were dwarfed by the palace, whose arches formed an arcade of golden brick. It was actually a complex of buildings anchored to the large enclosing wall, with many courtyards and connecting arcades. Above were domes and cupolas and small towers, perfectly symmetrical, catching the last beams of sunlight that no longer reached to the ground. The walls were decorated with myriad geometric carvings whose intricacy was amazing; an army of artisans had had to labor to fashion every detail. Seen from a distance, the palace was a marvel of architecture; seen close, it was a marvel of design.

Yet it was even more impressive inside. Ana had to murmur a word of caution to Scevo to prevent him from turning his head to gaze in open wonder. The impression was one of openness, of spaciousness, as if the palace were larger inside than outside. Now the interiors of the cupolas could be seen, forming patterns of cleverly fitted stonework, with inward projections reminiscent of the stalactites of large caves. Ornate columns

descended to the floor, each perfect in its slender strength. The floor was tiled, with each chamber of a different design, some simple squares within squares, others so finely wrought as to dazzle the eye by their color and patterning. The walls were decorated with artistic inlays, notably of the finely glazed many-colored pottery called faience, forming flowing Arabic script: quotations from the Koran. Some walls were honeycombed with small alcoves, adding to the decoration.

Now they encountered one of the Divan, the corps of government officials. The name came from the couches set around the walls of the council hall in which they met. The master of ceremonies, Raay, hurried up. “I am really glad to see you,” he said. “The sultan remains somewhat fatigued from his recent campaign in the west, and is in a foul mood. Heads will fly if it isn't eased.” Muhammad, not content with the title of Shah, had assumed the title of Sultan, the Sword of Islam, and no one had the power to object. He also liked to be addressed by titles such as “The Warrior,” or “The Great,” “The Second Alexander,” and “The Shadow of Allah upon Earth.”

They were indoors now, but neither Ana nor Miin removed their veils or showed their faces. They would not let any man see them, other than the head of their household. Only infidels, such as Christian women, had the bad taste to show their bare faces in public.

“What set him off this time?” Huu asked. They had dealt with this officer many times, entertaining for lesser royalty during the absence of the Shah, and knew Raay would not report them for veiled uncomplimentary references. Those closest to the Shah tended to be somewhat nervous, because he was arrogant to the point of folly, and could take savage reprisals for trifling inadvertent affronts. There was a tacit conspiracy of silence about such things in the palace, and all the staff and artisans protected each other whenever they could.

For indeed, Shah Muhammad's rages were legendary. Only the year before, he had made a triumphal procession through Persia, accepting homage from all the lords and governors of his empire. During this travel he had come into conflict with the caliph at Baghdad. Muhammad had killed a holy man, a venerable sayyid, and as a matter of form asked for, then demanded, absolution from the caliph, the nominal spiritual head of the faith. The caliph had refused, and had some justice in his position, for the act had been reprehensible. Muhammad had then denounced the caliph and marched his mercenary army, complete with war elephants and trains of supply camels, westward toward the city. This was an act of outrageous presumption, but in the face of overwhelming power an accommodation was possible, and the caliph was about to be replaced. Actually the expedition did not reach Baghdad, because it had encountered the formidable Zagros mountain range just as a particularly harsh winter set in.

The Shah's forces were not inured to the hardships of a mountain passage in such conditions; horses starved and men froze. So, with bad grace, he had turned back. But the caliph knew that the mountains would not stop the Shah when spring came. The Shah had won his point, but had made an enemy of the entire spiritual establishment of Islam. The caliph refused to recognize Muhammad or to put his name in public prayers. There were those here in Samarkand who hated the Shah, for that reason, but of course none spoke aloud of it.

“It's the message from the Mongol,” the master of ceremonies said. “The Shah has put out word to slay all Mongol sympathizers without hearings.”

“That must have been an ugly message,” Ana remarked.

“The odd thing is that it wasn't,” Raay said. “It could have been taken as a gesture of friendship. But a single word gave it the lie. The khan called the Shah his son.”

Huu coughed, and Miin put a hand to her mouth to stifle a titter. They all knew that in the language of diplomacy, sons were vassals, owing primary allegiance to their fathers. It was as if the Mongol had simply annexed the empire of Kwarizm to his own, making the Shah his servant.

“The impertinence of the man,” Ana said. “And he couched it as a message of friendship?”

“Including gifts,” Raay said. “For the good child.” He made a droll expression; he was being ironic.