Shakespeare: A Life (63 page)

Read Shakespeare: A Life Online

Authors: Park Honan

Tags: #General, #History, #Literary Criticism, #European, #Biography & Autobiography, #Great Britain, #Literary, #English; Irish; Scottish; Welsh, #Europe, #Biography, #Historical, #Early modern; 1500-1700, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Performing Arts, #History & Criticism, #Shakespeare, #Theater, #Dramatists; English, #Stratford-upon-Avon (England)

But one night with her, every hour in't will

Take hostage of thee for a hundred, and

Thou shalt remember nothing more than what

That banquet bids thee to.

(I. i. 174-85)

'To thee no star be dark', the Queens later hail Theseus. 'Both heaven and earth friend thee for ever.'

His collaborator did not try to match that elegance. Fletcher works up Palamon and Arcite's friendship, their

au courant

talk, Emily's bemused love and a sub-plot about madness, infatuation,

and sex. His medieval knights become Jacobean courtiers -- Palamon,

as critics notice, is like the bed-hopping Pharamond in Beaumont and

Fletcher Philaster. In the subplot about a Jailer's Daughter whose

love for Palamon leads to her madness, Fletcher sets city against the

country, exalting an urban aristocracy at the expense of showing rural

folk as quaint or naïve, and thus he surely appeals to élite

play-goers. His writing in the sub-plot is quick, depthless, and

nasty, if not amoral -- and thanks to him, this play reflects an

absolute ending of the 'Elizabethan compromise', or that vital, social

cohesion in audiences which once led dramatists to write for all

ranks.

29

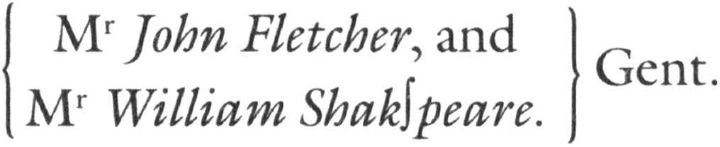

Excluded from the Folio of the older poet's works, The Two Noble

Kinsmen was printed in a quarto, of 1634, by Thomas Coates as having

been

Written by the memorable Worthies of their time;

Though it comes first alphabetically, Fletcher's name is probably mentioned first because he had written most of the drama.

In the spring of 1613, by which time two or three of these plays were

finished, Shakespeare bought his first property in London. This was

the Blackfriars gatehouse, which as the name suggests stretched over

-378-

a gate in the thick eastern wall of the priory complex. As a centre of

intrigue and a hideaway for priests, it had an almost visible history:

'it hath sundry back-dores and bye-wayes, and many secret vaults and

corners', Richard Frith, of the Blackfriars district, had once told

the authorities. A priest might handily escape through 'secret

passages towards the water' -- and only a few paces down St Andrew's

Hill, one came to Puddle Wharf, waiting boatmen, and the flowing

Thames.

On 10 March 1613, Shakespeare

agreed to pay the gatehouse's owner, Henry Walker, a citizen and

minstrel of London, £140 -- or perhaps more than the cost of his New

Place. A day later, he put up £80 in cash and signed a mortgage deed,

stipulating that the balance would be paid on 29 September

(Michaelmas), but the mortgage was still unpaid when he died.

In business deals he could be lax, but he also took peculiar pains

here. The title deed shows that he had three co-purchasers, William

Johnson, John Jackson, and John Hemmyng, none of whom put up a penny.

The latter presumably was his colleague in the King's troupe, Johnson

was landlord at the Mermaid, and Jackson perhaps was the man who had

wed the sister-in-law of Elias James, the young brewer. One effect of

this arrangement was that Anne Shakespeare was denied a dower right in

the gatehouse, even if her husband died intestate. In English common

law, a widow was barred from a claim on property of which her husband

was not the sole proprietor. It is said, in a modern account of the

purchase, that this was a speculative investment, 'pure and simple',

because the poet had a tenant at the gatehouse.

30

But that badly neglects dates. The tenant, John Robinson, was there

in 1616. Three years earlier, Shakespeare possibly had other aims and

requirements. He was to stay over in London for weeks, as we know from

Greene Diary, and as a

pied-à-terre

the gatehouse would have

been on the doorstep of one theatre, and just across the water from

the Globe. His troupe's stock of his playbooks was close at hand, and

there is no sign that he did not, at first, aim to live and work at

Blackfriars.

Still, a disaster may

have affected his plans. This occurred less than four months after his

new purchase on a day when the Globe was crowded. At the thatched

amphitheatre on Tuesday, 29 June 1613, the players had a new drama

called All is True, 'representing some

-379-

principal pieces of the reign of Henry VIII', as Sir Henry Wotton

wrote on 2 July. The phrase 'a new play' may only mean that Henry VIII

was then relatively new, since on 4 July Henry Bluett, a young

merchant, wrote that the drama 'had been acted not passing 2 or 3

times before'. Wotton, though, best tells us how some thatch caught

fire, and flames ran around inside the roof, but fanned by the wind,

so that in a short time the whole grand Globe was consumed. The play

itself, he writes, 'was set forth with many extraordinary circumstances

of pomp and majesty, even to the matting of the stage; the Knights of

the Order, with their Georges and garters, the Guards with their

embroidered coats and the like'. The garish spectacle, on stage, held

nearly every eye.

Now,

King Henry making a masque at the Cardinal Wolsey's house, and certain

chambers [i.e. pieces of small ordnance] being shot off at his entry,

some of the paper, or other stuff, wherewith one of them was stopped,

did light on the thatch, where being thought at first but an idle

smoke, and their eyes more attentive to the show, it kindled inwardly,

and ran round like a train, consuming within less than an hour the

whole house to the very grounds.This

was the fatal period of that virtuous fabric, wherein yet nothing did

perish but wood and straw, and a few forsaken cloaks; only one man had

his breeches set on fire, that would perhaps have broiled him, if he

had not by the benefit of a provident wit put it out with bottle ale.

Bluett adds that nobody was hurt in the fire, 'except one man who was

scalded . . . by adventuring in to save a child which otherwise had

been burnt'.

32

Was he the one whose breeches were doused with bottled ale? Puritans

saw God's hand in the 'sudden fearful burning', and a wit produced a

ballad on the terrible conflagration:

Had it begun below, sans doubt,

Their wives for fear had pissed it out.

Oh sorrow, pitiful sorrow, and yet all this is true.

33

Yet almost at once the King's men decided to build a new Globe, on

the same site, with a tiled roof. That was to cost approximately

£1,400-£1,500, an enormous sum, and each sharer was assessed heavily at

£50 or £60, and later more.

The landlord negotiators for the new Globe were Heminges, Con-

-380-

dell, and the two Burbages. Heminges had already given up acting, and

two other King's sharers -- Alexander Cooke and William Ostler --

were to die in the next year. Despite his house at Blackfriars,

Shakespeare probably felt that it was time to sell his theatre shares.

He would thus have avoided paying towards the new Globe, which, with

incrementing costs, took a year to build. His shares, at any rate, were

sold before he made his will. The limited number of 'housekeepers'

who put money into the new Globe may explain why Richard Burbage, then

near the end of his days, was worth little more than £300 a year when

he died. Shakespeare may have felt that his own new work was of less

use to the King's men; and his writing in Two Noble Kinsmen is far

from Fletcher's mode. That play was staged in 1613-not later than the

autumn -- and Shakespeare was to be in London again, near his ageing,

sweating colleagues. He may not have given up acting, but his writing

career was over by the end of the year.

-381-

A GENTLEMAN'S CHOICES

We make trifles of terrors, ensconcing ourselves into seeming

knowledge when we should submit ourselves to an unknown fear.( Lafeu, in

All's Well Tbat Ends Well

)Why, thou owest God a death.

( Prince Hal to Falstaff)

We cannot but know [your] dignity greater, than to descend to the

reading of these trifles: and, while we name them trifles, we have

depriv'd our selves of the defence of our Dedication. But since your

Lordships

have beene pleas'd to thinke these trifles some-thing . . . we hope,

that (they out-living [MR. Shakespeare], and he not having the fate,

common with some, to be exequutor to his owne writings) you will use

the like indulgence toward them.( John Heminges and Henry Condell, in their dedication of

MR. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies

( 1623) to the earls of Pembroke and Montgomery)

He had the good Fortune to gather an Estate equal to his Occasion',

wrote Nicholas Rowe in 1709 about Shakespeare, 'and is said to have

spent some Years before his Death at his native

Stratford'.

1

Rowe, one feels, is right in believing that the poet's estate was

ample, but the notion of retiring from all useful work was generally

speaking

-382-

not a common one. With energy, health for travel, and an active mind

Shakespeare did not spend all of his time at home. He had his reasons

no doubt for a long stay in the capital in 1614, at just the time the

King's men played at court. He did not hurry home.

Stratford was not a tomb, but there the tempo and scope of his life

were reduced, and the exciting and challenging unpredictability as

well as the strange illusory grandeur of a calling that had marked him

were absent. Public-theatre plays 'were conceived for production on a

generous scale before large audiences' -- and always there had been 'a

need for grand effect and gesture' in chancy, provisional staging.

2

The grandest gestures could fail, no troupe's viability was ever

certain, and little had been secure for his fellows in his whole

working life.

There were losses for

him as he reached his fiftieth birthday in April 1614. His brothers

Gilbert and Richard had died almost within a year of each other, and

Shakespeare and his sister Joan were the only ones left of the Henley

Street family. His Aunt Margaret, the last of his mother's sisters,

was to be buried at Snitterfield on 26 August of the present year.

At New Place unfamiliar visitors might see him if only because the

house was adjacent to the chapel, and not far from the church. This

year a preacher stayed overnight, and to Anne the town allowed 20

p.

for a quart of sack and a quart of 'clarett' to wet his throat.

Preachers arrived to give the foundation sermons -- the Oken in

September, the Hamlet Smith at Easter, the Perrott at Whitsuntide.

To his immediate neighbours on the north side of his house at Chapel

Street, the poet was hardly a stranger. Nearby was Widow Tomlins,

whose husband John, a tailor, had once sued the poet's uncle Henry

Shakespeare. Close to the widow lived Henry Norman, his wife Joan, and

their four children, as well as George Perry the glover. In an odd,

stumpy dwelling, its garden bordering on New Place's 'great garden',

were the childless Shaws. Later a witness to the poet's will, July or

Julyns Shaw had joined the Gunpowder Plot inquiry. He slept upstairs

over his hall in a dining-room which served as a bedroom and looked

perhaps like the month of July -- it had a green rug, a large green

carpet, and five green curtains. A shrewd alderman, with funds from

malt and wool trading, he rose to the bailiwick in the last year of

Shakespeare's life.

3

-383-

Julyns was to prove useful to the poet. Also helpful was Thomas Greene, whose

Diary

this year records scraps of Shakespeare's talk during a crisis over

land enclosure, in which Mrs Bess Quincy (the bailiff's widow) and the

town's women were defiant. The poet's daughter Judith had helped

Mistress Quiney, and the land crisis itself is illuminated by Greene.

He and his brother John, who was also active at Stratford, were called

to the bar; John was a lawyer of Clements Inn. From the Middle

Temple, Greene had been solicitor for the Stratford Corporation,

before he served from 1603 to 1617 as borough steward (by patent) and

as town clerk. While waiting for a house, he had noted in September

1609, 'I mighte stay another ye

a

re at New Place'.

4

At the time, he and his wife Lettice, of West Meon in Hampshire, and

their small children Anne and William, born in 1604 and 1608, were

living as Anne Shakespeare's guests, but within a few months they had

settled at St Mary's House near Holy Trinity.

Mainly the poet had been an absentee, and local clerks forgot him.

That may explain why, at first, his name was omitted from a subscription

list in 1611, drawn up to get funds 'towards the charge of prosecuting

the bill in parliament for the better repair of the highways'. On a

roster, leading men of Stratford are listed in a column of seventy

names; against one, the sum of 2

s.

6

d.

is marked. Far to the right, the name 'm

r

William Shackspere'is added, it seems as an afterthought, as if someone had recalled he was still alive.'

5

A year or two later, he was almost too much in the light, and the

town's temper was uneasy. His elder daughter had had trouble. In 1613

Susanna Hall had sued John Lane junior, for slander in a case she

brought before the consistory court at Worcester cathedral on 15 July.

Susanna claimed that Lane 'about 5 weeks past' had reported that she

'had the running of the reins & had been naught with Rafe Smith at

John Palmer'. (The 'reins' were the kidneys, or loins. To have 'running

of the reins' meant to have gonorrhoea, which did not always denote

venereal infection, though that is what is meant in this context.)

Susanna was then 30, with a child of 5; later she is called 'fidessima

conjux' (faithful wife) on her husband's gravestone. When M

r

Hall travelled, gossip fixed on his wife. Rafe or Ralph Smith, the supposed

-384-