Shadow and Betrayal

Read Shadow and Betrayal Online

Authors: Daniel Abraham

Table of Contents

SHADOW AND BETRAYAL

Marchat shook his wooly, white head slowly, his gaze never leaving hers. Amat felt the strength go out of his fingers.

‘If this comes out to anyone, I’ll be killed. At least me. Probably others. Some of them innocents.’

‘I thought there was only one innocent in this city,’ Amat said, biting her words.

‘I’ll be killed.’

Amat hesitated, then withdrew her arm and took a pose of acceptance. He let her stand. Her hip screamed. And her stinging ointment was all at her apartments. The unfairness of losing that small comfort struck her ridiculously hard; one insignificant detail in a world that had turned from solid to nightmare in a day.

At the door, she stopped, her hand on the water-thick wood. She looked back at her employer. At her old friend. His face was stone.

‘You told me,’ she said, ‘because you wanted me to find a way to stop it. Didn’t you?’

‘I made a mistake because I was confused and upset and felt very much alone,’ he said. His voice was stronger now, more sure of himself. ‘I hadn’t thought it through. But it was a mistake, and I see the situation more clearly now. Do what I tell you, Amat, and we’ll both see the other side of this.’

‘It’s wrong. Whatever this is, it’s evil and it’s wrong.’

‘Yes,’ he agreed.

Amat nodded and closed the door behind her when she went.

BY DANIEL ABRAHAM

The Long Price

Shadow and Betrayal

Seasons of War

Shadow and Betrayal

Seasons of War

Shadow and Betrayal

DANIEL ABRAHAM

Hachette Digital

Published by Hachette Digital 2010

Copyright © 2007 by Daniel Abraham

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All characters and events in this publication, other than those clearly in the public domain, are fictitious and any resemblance to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this bookis available from the British Library.

eISBN : 978 0 7481 2076 5

This ebook produced by JOUVE, FRANCE

Hachette Digital

An imprint of

Little, Brown Book Group

100 Victoria Embankment

London EC4Y 0DY

An Hachette Livre UK Company

To Fred Saberhagen,

the first of my many teachers

the first of my many teachers

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book and this series would not be as good if I hadn’t had the help of Walter Jon Williams, Melinda Snodgrass, Yvonne Coats, Sally Gwylan, Emily Mah-Tippets, S. M. Stirling, Terry England, Ian Tregillis, Sage Walker, and the other members of the New Mexico Critical Mass Workshop.

I also owe debts of gratitude to Shawna McCarthy and Danny Baror for their enthusiasm and faith in the project, to James Frenkel for his unstinting support and uncanny ability to take a decent manuscript and make it better, and to Tom Doherty and the staff at Tor for their kindness and support of a new author.

And I am especially indebted to Paul Park, who told me to write what I fear.

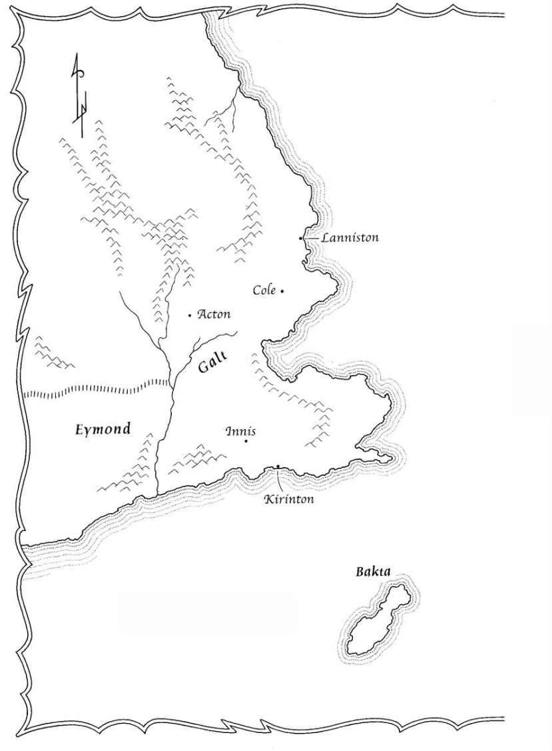

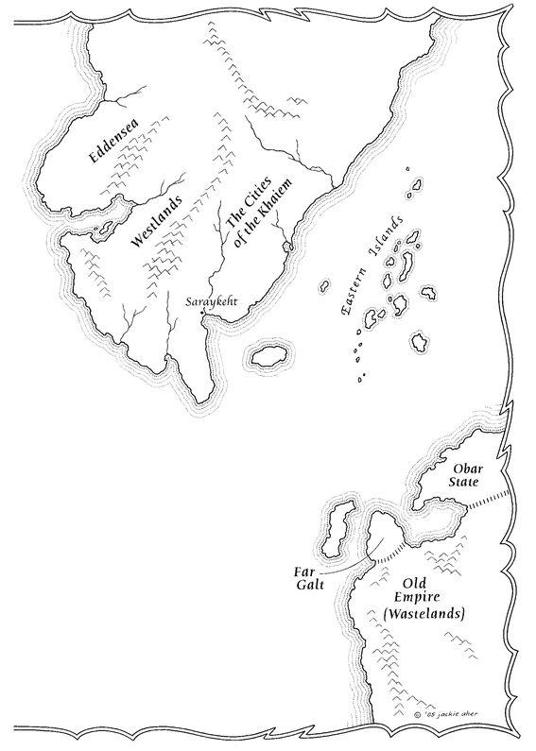

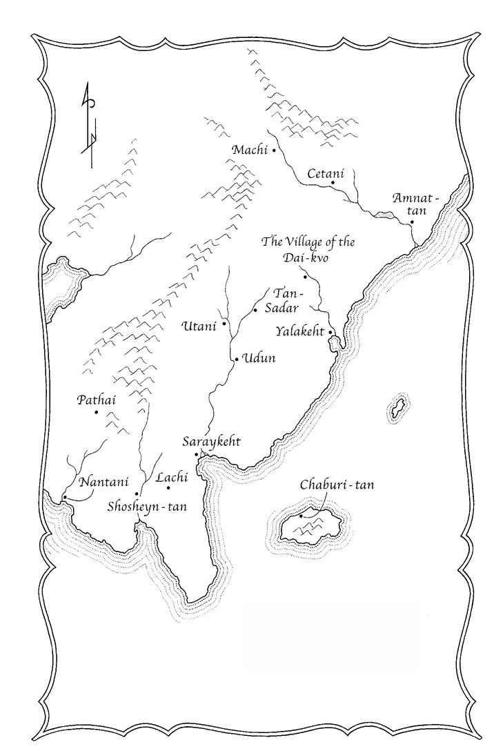

The World

The Cities of the Khaiem

BOOK ONE; A SHADOW IN SUMMER

PROLOGUEO

tah took the blow on the ear, the flesh opening under the rod. Tahi-kvo, Tahi the teacher, pulled the thin lacquered wood through the air with a fluttering sound like bird wings. Otah’s discipline held. He did not shift or cry out. Tears welled in his eyes, but his hands remained in a pose of greeting.

tah took the blow on the ear, the flesh opening under the rod. Tahi-kvo, Tahi the teacher, pulled the thin lacquered wood through the air with a fluttering sound like bird wings. Otah’s discipline held. He did not shift or cry out. Tears welled in his eyes, but his hands remained in a pose of greeting.

‘Again,’ Tahi-kvo barked. ‘And correctly!’

‘We are honored by your presence, most high Dai-kvo,’ Otah said sweetly, as if it were the first time he had attempted the ritual phrase. The old man sitting before the fire considered him closely, then adopted a pose of acceptance. Tahi-kvo made a sound of satisfaction in the depths of his throat.

Otah bowed, holding still for three breaths and hoping that Tahi-kvo wouldn’t strike him for trembling. The moment stretched, and Otah nearly let his eyes stray to his teacher. It was the old man with his ruined whisper who at last spoke the words that ended the ritual and released him.

‘Go, disowned child, and attend to your studies.’

Otah turned and walked humbly out of the room. Once he had pulled the thick wooden door closed behind him and walked down the chill hallway toward the common rooms, he gave himself permission to touch his new wound.

The other boys were quiet as he passed through the stone halls of the school, but several times their gazes held him and his new shame. Only the older boys in the black robes of Milah-kvo’s disciples laughed at him. Otah took himself to the quarters where all the boys in his cohort slept. He removed the ceremonial gown, careful not to touch it with blood, and washed the wound in cold water. The stinging cream for cuts and scrapes was in an earthenware jar beside the water basin. He took two fingers and slathered the vinegar-smelling ointment onto the open flesh of his ear. Then, not for the first time since he had come to the school, he sat on his spare, hard bunk and wept.

‘This boy,’ the Dai-kvo said as he took up the porcelain bowl of tea. Its heat was almost uncomfortable. ‘He holds some promise?’

‘Some,’ Tahi allowed as he leaned the lacquered rod against the wall and took the seat beside his master.

‘He seems familiar.’

‘Otah Machi. Sixth son of the Khai Machi.’

‘I recall his brothers. Also boys of some promise. What became of them?’

‘They spent their years, took the brand, and were turned out. Most are. We have three hundred in the school now and forty in the black under Milah-kvo’s care. Sons of the Khaiem or the ambitious families of the utkhaiem.’

‘So many? I see so few.’

Tahi took a pose of agreement, the cant of his wrists giving it a nuance that might have been sorrow or apology.

‘Not many are both strong enough and wise. And the stakes are high.’

The Dai-kvo sipped his tea and considered the fire.

‘I wonder,’ the old man said, ‘how many realize we are teaching them nothing.’

‘We teach them all. Letters, numbers. Any of them could take a trade after they leave the school.’

‘But nothing of use. Nothing of poetry. Nothing of the andat.’

‘If they realize that, most high, they’re halfway to your door. And for the ones we turn away . . . It’s better, most high.’

‘Is it?’

Tahi shrugged and looked into the fire. He looked older, the Dai-kvo thought, especially about the eyes. But he had met Tahi as a rude youth many years before. The age he saw there now, and the cruelty, were seeds he himself had cultivated.

Other books

Evening: Poetry of Anna Akhmatova by Anna Akhmatova

Cutter and Bone by Newton Thornburg

Urdangarin. Un conseguidor en la corte del rey Juan Carlos by Eduardo Inda, Esteban Urreiztieta

Defending the Dead (Relatively Dead Mysteries Book 3) by Sheila Connolly

The Killing Kind by Bryan Smith

Censoring Queen Victoria by Yvonne M. Ward

Zombie Killers: Ice & Fire by Holmes, John, Szimanski, Ryan

Trouble at the Arcade by Franklin W. Dixon

No Stars at the Circus by Mary Finn