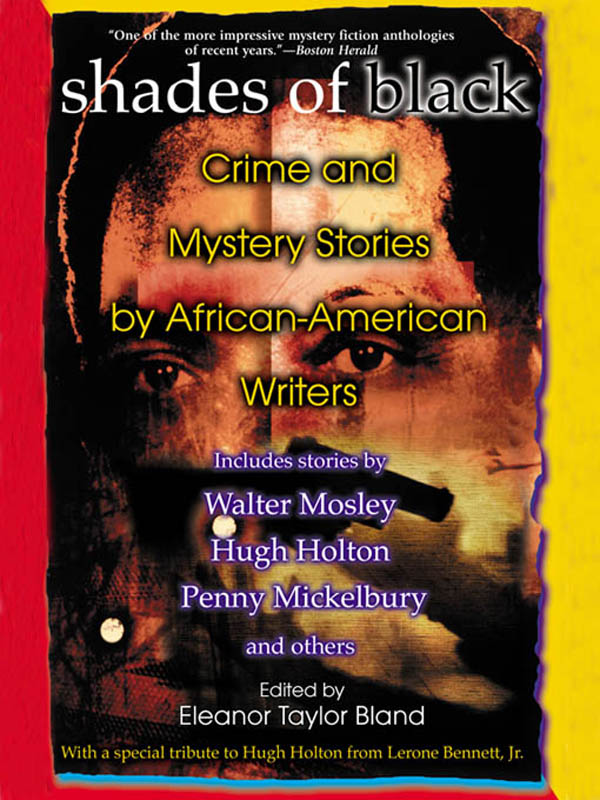

Shades of Black: Crime and Mystery Stories by African-American Authors

Read Shades of Black: Crime and Mystery Stories by African-American Authors Online

Authors: Eleanor Taylor Bland

INTRODUCTION: WHAT A DIFFERENCE A DECADE MAKES

Eleanor Taylor Bland

SINCE YOU WENT AWAY

Frankie Y. Bailey

THE COOKOUT

Jacqueline Turner Banks

MURDER ON THE SOUTHWEST CHIEF

Eleanor Taylor Bland and Anthony Bland

THE SECRET OF THE 369 INFANTRY NURSE

A Poplar Cove Mystery

Patricia E. Canterbury

DOGGY STYLE

Christopher Chambers

FOR SERVICES RENDERED

Tracy P. Clark

THE PRIDE OF A WOMAN

Evelyn Coleman

THE BLIND ALLEY

Grace F. Edwards

A MATTER OF POLICY

Robert Greer

SMALL COLORED WORLD

Terris McMahan Grimes

BETTER DEAD THAN WED

Gar Anthony Haywood

SURVIVAL

Dicey Scroggins Jackson

WHEN BLOOD RUNS TO WATER

Glenville Lovell

MORE THAN ONE WAY

Penny Mickelbury

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, business establishments, events or locales is entirely coincidental.

Â

Shades of Black: Crime and Mystery Stories by African-American Authors

Â

A

Berkley

Book / published by arrangement with the author

Â

All rights reserved.

Copyright ©

2004

by

Eleanor Taylor Bland and Tekno Books

This book may not be reproduced in whole or part, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission. Making or distributing electronic copies of this book constitutes copyright infringement and could subject the infringer to criminal and civil liability.

For information address:

The Berkley Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Putnam Inc.,

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014.

Â

The Penguin Putnam Inc. World Wide Web site address is

http://www.penguinputnam.com

Â

ISBN:

978-1-1012-0483-2

Â

A

BERKLEY

BOOK®

Berkley

Books first published by The Berkley Publishing Group, a member of Penguin Putnam Inc.,

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014.

BERKLEY

and the “

B

” design are trademarks belonging to Penguin Putnam Inc.

Â

Electronic edition: February, 2005

“Introduction: What a Difference a Decade Makes,” by Eleanor Taylor Bland. Copyright © 2004 by Eleanor Taylor Bland.

“Since You Went Away,” by Frankie Y. Bailey. Copyright © 2004 by Frankie Y. Bailey.

“The Cookout,” by Jacqueline Turner Banks. Copyright © 2004 by Jacqueline Turner Banks.

“Double Dealing,” by Chris Benson. Copyright © 2004 by Chris Benson.

“Murder on the Southwest Chief,” by Eleanor Taylor Bland and Anthony Bland. Copyright © 2004 by Eleanor Taylor Bland and Anthony Bland.

“The Secret of the 369th Infantry Nurse,” by Patricia E. Canterbury. Copyright © 2004 by Patricia E. Canterbury.

“Doggy Style,” by Christopher Chambers. Copyright © 2004 by Christopher Chambers.

“For Services Rendered,” by Tracy P. Clark. Copyright © 2004 by Tracy P. Clark.

“The Pride of a Woman,” by Evelyn Coleman. Copyright © 2004 by Evelyn Coleman.

“The Blind Alley,” by Grace F. Edwards. Copyright © 2004 by Grace F. Edwards.

“A Matter of Policy,” by Robert Greer. Copyright © 2004 by Robert Greer.

“Small Colored World,” by Terris McMahan Grimes. Copyright © 2004 by Terris McMahan Grimes.

“Better Dead Than Wed,” by Gar Anthony Haywood. Copyright © 2004 by Gar Anthony Haywood.

“The Werewolf File,” by Hugh Holton. Copyright © 2004 by Hugh Holton. Published by permission of the agent for the author's Estate, Susan Gleason.

“Déjà Vu,” by Geri Spencer Hunter. Copyright © 2004 by Geri Spencer Hunter.

“Survival,” by Dicey Scroggins Jackson. Copyright © 2004 by Mary Jackson Scroggins.

“When Blood Runs to Water,” by Glenville Lovell. Copyright © 2004 by Glenville Lovell.

“A Small Matter,” by Lee E. Meadows. Copyright © 2004 by Lee E. Meadows.

“More Than One Way,” by Penny Mickelbury. Copyright © 2004 by Penny Mickelbury.

“Bombardier,” by Walter Mosley. Copyright © 2002 by Walter Mosley. First published in Black Book Magazine. Reprinted by permission of the author and his agents, the Watkins/Loomis Agency.

“A Favorable Murder,” by Percy Spurlark Parker. Copyright © 2004 by Percy Spurlark Parker.

“Beginner's Luck,” by Gary Phillips. Copyright © 2004 by Gary Phillips.

“God of the Pond,” by Charles Shipps. Copyright © 2004 by Charles Shipps.

Lerone Bennett Jr.

While researching and writing history books, I relax by reading murder mysteries, which keep the pot of my mind simmering and which remind me of what sleuth Larry Cole called real history. During these periods, and the periods in between, I read all of the great masters of the craft, Christie, Allingham, James, Hugh Holton, Chandler . . . Wait a minute! Back up! Hugh Holton?

Yes, Hugh Holton, Chicago police captain and creator of Deputy Police Chief Larry Cole, and also Chester Himes, Walter Mosley, Grace Edwards, and other African-American masters who have not received proper recognition for their contribution to this genre. Within recent years, primarily because of the Freedom Movement, which changed the color of almost everything, including the color of some police chiefs, writers like Mosley, Eleanor Bland, and my colleague Chris Benson are reaching a wider audience. They are also reminding us that mystery writers from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to Dame Agatha Christie assumed a natural order in which all police chiefs and police captains were White. But that's another story or rather another part of the same story, for there is still a tendency to relegate African-American writers to a lower order of the realm.

This anthology warns against that conceit and invites us to a reevaluation of major and neglected talents who added multiple dimensions, including the why-dunit and the race-dunit, to the traditional and limited whodunit.

Hugh Holton is particularly relevant in this connection, because he spoke not from the library but from the precinct. A full-time police officer

and the highest-ranking police officer writing mystery stories at the time, he provided a new perspective and spoke to us from a fully realized world that included murderers living in penthouses and murderers stalking the street.

I don't think there is a finer rendition anywhere of urban police and detective rituals than in Holton's novels. Nor, I think, is there a finer rendition of the

structures

of crimes that create drug addicts, criminals, and crime-fighters the same way Detroit assembly lines turn out cars. Where else can we find a Martin Luther King Jr. march (in his novel

Criminal Element

) defining and anticipating the paths of a rogue cop or a more perfectly drawn portrait, in a crime scene setting, of a Black man rising from the cotton fields to Congress. But I don't want to make this too heavy. For Captain Hugh Holton didn't write essays; he wrote mystery stories that included structure, atmosphere, layers,

the whole,

because he knew that a good mystery story, like any other piece of art, is a world that includes, at least by implication, everything. More than this, Hugh Holton knew that his task was not to preach or teach but to

show

the world and to make us freely re-create it and assume responsibility for it.

I have always preferred the traditional whodunit that gives you the clues and challenges you to identify the murderer. It can be said that Holton's art is greater than that, for he tells you who the murderer is and how he did it and then makes you sit on the edge of your seat as layer after layer of explosions and revelations hold you enthralled until the last page.

On this level, and on others as well, Captain Hugh Holton was a rare talent who bore witness to a world that most of us deny but that none of us can ignore without diminishing art and freedom. In addition to all that, Holton, like Himes, the progenitor of the African-American police procedural, Mosely, and other writers featured in this anthology, was a great storyteller who increased our understanding of Black, White, and Brown humanity.

I did not become a mystery writer because I was a longtime fan. I discovered detective fiction in 1988, about two years before I began writing the Marti MacAlister mystery series. The only other African-American mystery writers I was aware of at that time were Chester Himes and Walter Mosley, neither of whom I had read. I had no idea of the long and significant history of African-Americans in this genre. I am deeply indebted to Frankie Y. Bailey and

Out of the Woodpile: Black Characters in Crime and Detective Fiction

for what I know now that I didn't know then.

I had read

The Conjure Man Dies: A Mystery of Dark Harlem,

written by Rudolph Fisher and published in 1932, but I did not know that prior to that, W. Adolph Roberts had published several mystery novels, including

The Haunting Hand

in 1926.

Native Son,

by Richard Wright, published in 1940, continues to be a major influence in my writing, but as a woman writer I did not know that in 1900, Pauline Hopkins published the short story “Talma Gordon,” a locked door mystery, in

Colored American Magazine.

Nor did I know that by 1907 short stories were being published by J. E. Bruce, or that other early African-American writers of mystery fiction include Alice Dunbar-Nelson, John A. Williams, and Sam Greenlee.

There is a rich tradition of African-Americans who wrote cozies and thrillers and every other mystery subgenre. Although not all of these writers had Black protagonists, those who did included the social and political issues of their time. They added a significant dimension to our rich and varied literary tradition. We are all deeply indebted to them as well as enriched by them.

In keeping with our literary traditions, history, and heritage, this smorgasbord of short stories includes writers whose work you know and love, writers who are published in other genres, and a few writers who are being published here for the first time. Their stories vary from cozy to suspense; their protagonists vary in age from young adult to senior citizen and include a wide variety of sleuths as well as varied locales. Alternative viewpoints on social and political issues, our own unique perspective of the world we live in, and even an element of fantasy and science fiction are included. In short, we have brought to this work what is representative of who we are as writers, and as African-American writers.

Eleanor Taylor Bland

In 1992, Gar Anthony Haywood and Walter Mosley were the only two African-Americans publishing mystery novels. Percy Spurlark Parker, who published a mystery novel in 1974, was publishing short stories.

Before that year was over, Barbara Neely and I published our first mysteries. Four years later, in 1996 fifteen of us gathered at the University of Minnesota in St. Paul-Minneapolis, at the invitation of Archie Givens Jr., to attend a three-day Black Mystery Writer's Symposium in conjunction with Bouchercon XXVII. Today we have approximately forty-six African-Americans who have published mysteries. And, I hope, we're still counting.

In my opinion, the most significant contribution we have made, collectively, to mystery fiction, is the development of the extended family; the permanence of spouses and significant others, most of whom don't die in the first three chapters or by the end of the novel; children who are complex, wanted, and loved; and even pets. We have brought our mothers and fathers, or grandparents, and other relatives and friends to our work in a uniqueâoften humorous, frequently reverent, and sometimes brutally honestâtribute to who they are, all they have survived, and what they have given. As writers of fiction we have added a new depth and

dimension to members of the opposite sex. Women write about caring and compassionate men who are also strong and self-sufficient. Men write about women who are independent and intelligent and also affectionate, giving, and accurately strong.

We write about sleuths who are gumshoesâboth hard core and relatively benevolent private investigatorsâpolice officers, former police officers, FBI agents, attorneys, forensic scientists, domestic workers, bail bondsmen, doctors, a drug addict, an ex-convict, journalists, historians, educators, political and community activists, concerned citizens, and citizens trying to mind their own business.

We write about things common to everyone, and things uniquely our own, such as '50s doo-wop music groups; life in Los Angeles in the '50s and '60s as well as the present; blues from the 1960s to the new millennium; lynching and the death penalty from 1912 to 1922; the Underground Railroad; and Black genealogy. References to religion and a religious context to right and wrong are not unusual. Problems of color, what shade of Black you are, is also referenced. We give visibility, context, and dimension to issues, dilemmas, and society that are often invisible to others.

We write about familiar places like L.A., Boston, Baltimore, Philly, New Orleans, Northern California, Colorado, Maine, Missouri, and Virginia, as well as less familiar, more stereotypical places like Newark, Harlem, Detroit, Chicago, and Washington, D.C., small towns in particular and the South in general, from our own unique perspectives.

I have withheld the identity of the authors of these works, because I am hoping that you will go to your independent booksellers, libraries, chain stores andâbased on your own interests and curiosityâfind out who these authors are. I am also hoping that such forays will open up to you the entire, exciting world of African-American Mystery Fiction. Keep reading . . .