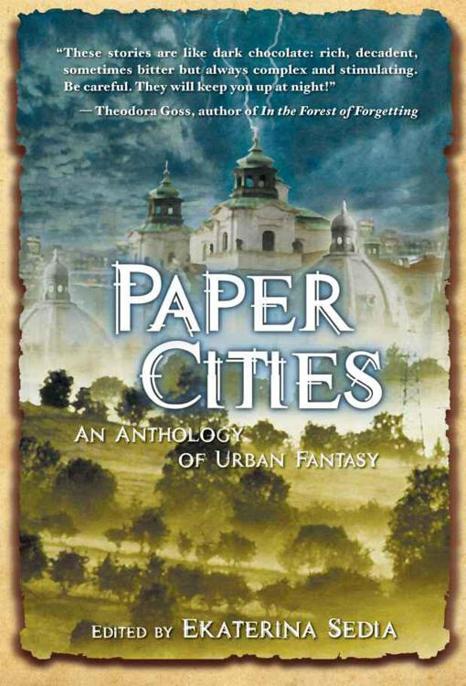

Paper Cities, an Anthology of Urban Fantasy

Read Paper Cities, an Anthology of Urban Fantasy Online

Authors: Ekaterina Sedia

Tags: #Literature & Fiction, #Short Stories & Anthologies, #Anthologies, #Science Fiction & Fantasy, #Fantasy, #Epic, #Paranormal & Urban, #Anthologies & Literature Collections, #Contemporary Fiction, #Genre Fiction, #Anthologies & Short Stories

Senses Five Press

www.sensesfive.com

[email protected]

Also by Ekaterina Sedia:

According To Crow

The Secret History Of Moscow

The Alchemy of Stone

Also from Senses Five Press

Sybil’s Garage Issues 1 — 6

This is a work of fiction. All characters and events portrayed in this book are either fictitious or used fictitiously.

Collection copyright © 2008 Senses Five Press.

Digital edition copyright © 2009 Senses Five Press.

All Rights Reserved.

Copyrights for the individual stories and the foreword remain the property of the authors.

This section

functions as an extension of the copyright page.

Senses Five Press

www.sensesfive.com

[email protected]

Paper Cities, An Anthology of Urban Fantasy

Edited by Ekaterina Sedia

ISBN 978-0-9796246-0-5

Cover art by Aaron Acevedo (

http://aaronace.com

).

Cover design & print-version layout by Kris Dikeman.

Digital e-book design: Kris Dikeman & Matthew Kressel (

http://www.matthewkressel.net

)

Copy-editing by Darin C. Bradley (

http://darinbradley.livejournal.com/

).

Forrest Aguirre

•

Andretto Walks the King’s Way

Hal Duncan •

The Tower of Morning’s Bones

Richard Parks •

Courting the Lady Scythe

Cat Rambo •

The Bumblety’s Marble

Jay Lake •

Promises; A Tale of the City Imperishable

Greg van Eekhout •

Ghost Market

Stephanie Campisi •

The Title of This Story

Mark Teppo •

The One That Got Away

Paul Meloy •

Alex and the Toyceivers

Michael Jasper •

Painting Haiti

Kaaron Warren •

Down to the Silver Spirits

Darin C. Bradley •

They Would Only be Roads

Anna Tambour •

The Age of Fish, Post-flowers

Barth Anderson •

The Last Escape

The stories collected in this anthology range across historical periods and places real and imagined. But they all take place within cities —and they all talk about what urban life means. I selected these stories because they share the insight into the cities as living entities, benign or sinister, that can shape the existence of their inhabitants. And they share the passion for those agglomerations of flesh and inanimate matter, with all their foibles, glories, and hidden truths. Some of the authors are well-known; others are brand new and just starting to make a name for themselves. I love all of these stories, and I hope that the readers will as well.

— Ekaterina Sedia, New Jersey, August 30th 2007.

by Jess Nevins

One of the appealing things about Urban Fantasy is that, as John Clute points out in the

Encyclopedia of Fantasy

, it is a mode of storytelling rather than a subgenre, and as such accommodates a variety of themes and approaches. Urban Fantasy is not restricted by genre limitations the way that cyberpunk, hardboiled detective fiction, the Western, and pirate romances (among others) are. Urban Fantasy can be about almost anything — and

Paper Cities

is an excellent example of this.

We can trace the Urban Fantasy as far back as the

Arabian Nights

and the stories of Haroun al-Raschid wandering around Baghdad incognito and finding adventure. Similarly, the Gothics of the late 18th and early 19th centuries provided the Urban Fantasy with several basic elements, especially the ever-present backdrop of a circumscribed location, usually a castle but sometimes a mansion and occasionally even a city, as the setting for a story’s plot. But the Urban Fantasy as we now recognize it began in the 1830s and the 1840s.

The tendency in fiction to portray cities as both a setting and as a type of supporting character began in the 1820s, with John Polidori’s “The Vampyre” (1819), the first modern urban horror story, and with the Newgate novels, early versions of crime novels which told the biographies of criminals and illustrated the lives and

milieu

of the urban underclass. Victor Hugo, in

The Hunchback of Notre Dame

(1831), made Paris into the main character of the novel, much more so than the hunchback Quasimodo, and Eugene Sue did the same in his hugely popular

The Mysteries of Paris

(1842-1843) and to a lesser extent in the only slightly less popular

The Wandering Jew

(1844-1845), but Sue added an element of the fantastic which Hugo refrained from. In

The Mysteries of Paris

the lead character, Rodolphe von Gerolstein, is almost supernatural in his ability to disguise himself, to be where he needs to be, and to know what he needs to know.

The Wandering Jew

has the explicitly supernatural character Ahasuerus, the Wandering Jew of medieval myth, as well as other less overtly sketched supernatural aspects. With

The Mysteries of Paris

and

The Wandering Jew

Sue established, for modern European and American audiences, the concept of the city as a location where the fantastic was not just possible but appropriate. The Newgate novels, and early urban crime stories like Pierce Egan the Elder’s

Life in London

(1821) and Lord Bulwer-Lytton’s

Pelham

(1828), had expanded the axis in which urban stories could occur, from “peaceful” to “criminal.” Sue established a new axis: “realistic” to “fantastic.”

What followed in England and Europe was a widespread use of this concept. Dickens followed the example of Hugo and Sue and wrote stories in which the city would seem to be the most appropriate venue for the fantastic, or stories which were fantastic in all but name, and in so doing established London as the archetypal City of the English-speaking literate world. The 19th century saw a shift in population from rural to urban settings, and new, urban-centered forms of fiction arose, including the casebooks of the 1850s, proto-police procedural stories focusing on urban crimes, and the urban haunted house story, in Bulwer-Lytton’s “The Haunted and the Haunters” (1859). But looming over all successive writers was Dickens and the way in which he shifted the public’s frame of perception of the city. In Dickens’ hands London became an active participant in the story, an almost sentient location in which sentimentality, despair, and melodrama were mixed and heightened. At the end of the century Robert Louis Stevenson narrowed the portrayal of the city with his

New Arabian Nights

, a continuation of Dickens’ work. In applying the original

Arabian Nights

’ conception of the City to London as a place of wonders around every corner, Stevenson emphasized the purely fantastical elements and eliminated the politically activist and ideological elements of Sue’s and Dickens’ work.

However, for the American reader the urban milieu had a different set of associations and assumptions. The Puritans had seen the American frontier not as pristine, innocent wilderness but as an evil place which reflected men’s sins. This outlook colored 19th century American fiction, explicitly in the works of Hawthorne and less so in works like Robert Montgomery

Bird’s Nick of the Woods

(1837). But Americans had a similar distrust for the city. The most powerful expression of this distrust is in George Lippard’s

The Quaker City

(1844-1845), a vigorous portrayal of Philadelphia as an urban Hell rife with kidnapping, murder, and rape, whose redemption is only possible with an apocalyptic fire. This wariness of the city, and dread of what lies around its corners, is the recurring theme of American urban fiction, and can be seen in works as various as the short stories of Fitz-James O’Brian (see, for example, “The Wondersmith” (1859)), and the crime and Western dime novels. In the very popular Deadwood Dick (1877-1883) and Frank and Jesse James (1881-1903) dime novel series the communities of the settled frontier are harmonious, while New York City, and implicitly all Eastern cities, are locations where the corrupt and powerful prey on and victimize the innocent working man.

It was this tension between the city-as-full-of-wonder and the city-as-dreadful that primarily influenced 20th century Urban Fantasy. Neither can be described as primarily English or primarily American, as there are many counter-examples for each. Landmark European and English works of Urban Fantasy from the late 19th early 20th centuries portray the city as containing horrors in addition to wonders, including Victor von Falk’s 3000 page Grand Guignol masterpiece,

Der Scharfrichter von Berlin

(1890-1892), Bram Stoker’s

Dracula

(1897), Gaston Leroux’s

The Phantom of the Opera

(1910), and Thea von Harbou and Fritz Lang’s M (1931). And there are a number of examples of American Urban Fantasies whose cities tend more toward wonder than horror, from the Terri Windling-edited “Borderlands” series to Francesca Lia Block’s stories about Los Angeles. But as a broad tendency American Urban Fantasies begin with the assumption that the city is innately flawed and horrible; examples include Batman’s Gotham City (an exaggerated form of New York City), the Chicago of Fritz Leiber’s “Smoke Ghost” (1941), the New York City of Angela Carter’s

Passion of New Eve

(1977), and the Seattle of Megan Lindholm’s

Wizard of the Pigeons

(1986). English/European Urban Fantasies tend to portray the city in a more benign fashion, even if, as in the novels of Terry Pratchett and China Miéville, the city has its realistically horrible aspects.

Which brings us, at last, to

Paper Cities

. As a mode of storytelling Urban Fantasy is almost two hundred years old, but as a distinctive publishing subgenre Urban Fantasy dates back only to the 1980s. Authors like Charles de Lint, Emma Bull, and Megan Lindholm helped establish Urban Fantasy and gave it its distinctive character. But, as traditionally happens with new literary genres, the second generation of Urban Fantasy authors are pushing against the boundaries laid down by the first generation’s writers and taking the genre into new and welcome territories. The stories in

Paper Cities

not only draw on numerous inspirations but, entertainingly and skillfully, apply the Urban Fantasy mode to both non-Western cultures and to other subgenres and fictional forms. Darin C. Bradley’s “They Would Only Be Roads” recasts urban fantasy as a cyberpunk story, complete with grit, street-level programmers, a decaying urban milieu, and the possibility of romance and redemption. Hal Duncan’s “The Tower of Morning Bones” is a vivid Joycean mosaic; like Hal’s

Vellum

and

Ink

, “The Tower of Morning Bones” mixes old mythologies and a joy in the power of language to create something uniquely Duncanian. Barth Anderson’s “The Last Escape” takes the story of a heroic rebel in a dark direction, unexpectedly moving from superheroics to horror. Jay Lake’s “Promises” is, like his other City Impenetrable stories, atmospheric, harsh, and decadent (if not Decadent), but it also has a core of emotion and sadness which most Decadence lacks. Paul Meloy’s “Alex and the Toyceivers” reminds us that the suburbs and outer boroughs are also fitting locations for urban fantasy, especially stories involving children and pets.

Anna Tambour’s “The Age of Fish, Post-Flowers” is a post-civilization breakdown monster story, but Tambour eschews the predictable action movie heroics and explosions and concentrates on the cost to humans of surviving in an inhospitable environment. Mark Teppo’s “The One That Got Away” is a knowing riff on the Club Story, but from a 21st century perspective. “The One That Got Away” is about what Lord Dunsany’s Mr. Jorkens might have had to endure if he lived in the real world. Stephanie Campisi’s “The Title of This Story” is not particularly easily classified, as it is equal parts urban decadence, Borgesian horror, decadence, and lexigraphic fantasia; if it must be placed in one category, the only apposite one is “Campisian.” Greg van Eekhout’s “Ghost Market” is urban horror, grim, sad, and a quietly savage slap at a modern culture which slights the deaths of ordinary people, reducing them to statistics, and gives undue weight to the deaths of celebrities. Richard Parks’ “Courting the Lady Scythe” uses a traditional fantasy backdrop to tell a story that is both a be-careful-what-you-wish-for story, with its inevitable twist, and a bittersweet romance. Ben Peek’s “The Funeral, Ruined” is a kind of sequel to his “The Souls of Dead Soldiers are for Blackbirds, Not Little Boys.” “The Funeral, Ruined” uses an alien necropolis and a wounded veteran to consider the definition of the self and to topically remind the reader of what a society forces its soldiers to endure.

Jenn Reese’s “Taser” has magic and demon dogs and telepathy, but those are external elements; “Taser” is ultimately a story about life on the street as a member of a teen gang, and as such would have fit comfortably, even with its fantasy elements, in

The Saturday Evening Post

in the 1950s, or next to

West Side Story

in the 1960s, or

The Outsiders

in the 1970s. Cat Sparks’ “Sammarynda Deep” begins as an Arabian Fantasy and ends as a melancholy romance and consideration of the cost of honor. David Schwartz’s “The Somnambulist” is an examination of the cost of magic and what a relationship with a sorcerer might actually entail, and also a sharp metaphor for a certain type of husband. Kaaron Warren’s “Down to the Silver Spirits” is a maternal horror story which will resonate with mothers, and a marriage horror story which will resonate with husbands, and a parental horror story which will resonate with mothers and fathers. Steve Berman’s “Tearjerker,” one of his Fallen Area stories, is both an homage to Samuel Delaney and a meditation on victimization. Cat Rambo’s “The Bumblety’s Marble,” one of her Tabat stories, uses the structure of the traditional fairy tale to tell a colorful urban picaresque coming-of-age story. Michael Jasper’s “Painting Haiti” is about the power of art and the call of family ties, and provides a welcome reminder that cities are rarely monoculture, and that even fantasy cities have immigrants. Forrest Aguirre’s “Andretto Walks the King’s Way” uses the vocabulary of traditional fantasy to invoke Edgar Allan Poe and Mervyn Peake and perhaps tell an AIDS parable. And Catherynne Valente’s remarkable “Palimpset” is an evocative work of Decadence that superbly blends Valente’s distinctive, lush style with a memorable fictional world.

If

Paper Cities

is any indication of second-generation Urban Fantasy — and I believe it is — both the mode of storytelling and the subgenre have a bright future.

Jess Nevins

Hunstville, Texas

August, 2007