Shackleton's Heroes (6 page)

Read Shackleton's Heroes Online

Authors: Wilson McOrist

They had reached Antarctica. Their adventure was about to start.

1.

Shackleton,

South

2.

Mackintosh letter to G. Marston, 27 February 1913

3.

A. L. A. Mackintosh,

Shackleton's Lieutenant: The Nimrod Diary of A. L. A. Mackintosh, British Antarctic Expedition, 1907â09

(Christchurch: Stanley Newman, Polar Publications, 1990)

4.

Richards letter to L. B. Quartermain, 9 November 1960

5.

Shackleton letter to Mackintosh, 18 September 1914

6.

E. Joyce,

The South Polar Trail: The Log of the Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition

(London: Duckworth, 1929)

7.

Sydney Morning Herald

, 29 June 1914

8.

Richards,

The Ross Sea Shore Party

9.

Spencer-Smith diary, July 1915

10.

Hayward diary, July 1915

11.

Sydney Morning Herald

, 29 June 1914

12.

George Smith, headmaster at Merchiston Castle, Edinburgh, written reference for A. P. Spencer-Smith, 4 June 1912, supplied by Debby Horsman, great-niece of A. P. Spencer-Smith

13.

Naval Service Record of Harry Ernest Wild, No: 181904

14.

P. J. Hayward, grand-nephew of Victor Hayward. Private papers

15.

Willesden Chronicle

, 11 September 1914

16.

Ibid., 16 February 1917

17.

Shackleton letter to his wife Emily, 18 August 1914

18.

A. Stevens, report of the 1914â17 ATAE expedition, SPRI

19.

J. K. Davis,

With the

Aurora

in the Antarctic

1911â1914

(London: Andrew Melrose, 1919)

20.

Richards, interview with P. Lathlean, 1976

21.

The

Argus

newspaper, Melbourne, 11 November 1914

22.

P. J. Hayward, grand-nephew of Victor Hayward. Private papers

23.

Hayward postcard, 16 November 1914. NMM

24.

Spencer-Smith postcard to his parents, November 1914. Debby Horsman, great-niece of A. P. Spencer-Smith. Private papers

25.

Spencer-Smith, letter to his parents, 8 November 1914. Debby Horsman, great-niece of A. P. Spencer-Smith. Private papers

26.

Richards, interview with L. Bickel, 1976

27.

Richards telegram, 30 November 1914

28.

Richards letter to Mackintosh, 21 November 1914

29.

Richards letter to Mackintosh, 26 November 1914

30.

Richards,

The Ross Sea Shore Party

31.

Richards, interview with P. Lathlean, 1976

32.

Richards Agreement, 1 December 1914, SPRI

33.

Richards,

The Ross Sea Shore Party

34.

Spencer-Smith cablegram, 1914. Debby Horsman, great-niece of A. P. Spencer-Smith. Private papers

35.

Richards,

The Ross Sea Shore Party

36.

Joyce,

The South Polar Trail

37.

Richards,

The Ross Sea Shore Party

38.

Richards, interview with P. Lathlean, 1976

39.

Richards,

The Ross Sea Shore Party

40.

Hayward radio telegram to Ethel Bridson, 31 December 1914

41.

The Times

, 1 April 1914

42.

Joyce,

The South Polar Trail

43.

Mackintosh diary, 1 January 1915

44.

Ibid., 2 January 1915

45.

Ibid., 12 January 1915

46.

Ibid., 8 January 1915

47.

Richards interview with P. Lathlean, 1976

48.

Mackintosh diary, 1 January 1915

49.

Ibid., 3 January 1915

50.

Ibid., 1 January 1915

51.

Joyce,

The South Polar Trail

52.

Richards,

The Ross Sea Shore Party

53.

Mackintosh diary, 1 January 1915

54.

Ibid., 7 January 1915

55.

Shackleton letter to Mackintosh, 18 September 1914. In part this letter stated: âI would here inform you that the T-C party will carry sufficient provisions & equipment to cross right across to McM Sound but it is all important as we cannot tell what delays may ensure and what accidents may occur that the Southern depot from the Ross Sea should be laid.

âI make the above remark as regards the TC party equipment in case some very serious accident incapacitates your party from making a depot so that you may not have the anxiety of feeling that the T-C is absolutely dependent on the depot that you are to lay, but it is of supreme importance, as ensuring the absolute safe return of the TC party to have this depot laid.'

(TC and T-C means Shackleton's Trans-Continental Party.)

56.

Shackleton letter to Mackintosh, 18 September 1914

57.

Mackintosh diary, 13 February 1915

58.

Mackintosh diary, 16 June 1915

59.

Shackleton letter to Mackintosh, 18 September 1914. This letter also stated:

âPara 18: This paragraph is for your information only and you are to discuss it with nobody but follow implicitly these directions. If the TC party has not come out, and you go north, you must leave at Cape Evans or Cape Royds in a position easy for six men to handle, the best lifeboat belonging to Aurora. You must deck her over the foreport with canvas, or even deck her halfway along with a canvas cover and framework, she must have a good mast and sail, 12 oars, anchor and oil bag, a water breaker empty, sufficient sledging stores, oil and Primus cooker, to last two months, also sleeping bag and Burberrys; in fact the full equipment of a sledging party for six men for two months. You will also leave a sextant. The TC party will be equipped chronometers, nautical almanacs, etc. You should also leave a general chart of the ocean south of NZ. The reason for the equipment is as follows â should by any chance the TC party have arrived at winter quarters at the Ross Sea, after the ship has gone, I may decide to go north in the lifeboat. Under these circumstances I will make for Cape Adare then Macquarie Island, &

thence to Auckland Island and so on to Stewart Island. I do not wish you to wait at either M Island or A Island on the way up. If we can cross the ocean south of these islands there is nothing to prevent us reaching civilization generally.'

60.

Shackleton,

South

61.

Mackintosh diary, 1 January 1915

62.

Joyce,

The South Polar Trail

63.

Richards,

The Ross Sea Shore Party

64.

Mackintosh diary, 9 January 1915

65.

Richards,

The Ross Sea Shore Party

66.

Richards, interview with P. Lathlean, 1976

67.

Mackintosh diary, 9 January 1915

68.

Richards notes, Art & Historical Collection, Federation University (formerly University of Ballarat)

69.

Mackintosh diary, 10 January 1915

O

N 10 JANUARY

, the

Aurora

was stopped by thick sea-ice, deep in McMurdo Sound, about 4 miles to the south of Cape Evans, and 9 miles north of Hut Point. The ship was tied up to the ice edge.

1

It was a calm day and the ship became motionless and eerily quiet once the engines had stopped. The air was crisp and clear, almost breathlessly still, and Mount Erebus with its plume piling straight up into the sky dominated the view.

2

The men on the

Aurora

's deck looking south would see a flat expanse of dazzling white sea-ice stretching away as far as they could see, towards Hut Point.

Some of the men went out on the ice floes and tried their skills at skiing. In this Mackintosh thought that Wild proved the best whereas his own attempts were amateurish.

3

They also skied across the ice to visit the Cape Evans hut, located on a rocky cape. The wooden hut was on a beach of

coarse gravel, facing north-west and well protected by Mount Erebus and numerous small hills behind. Joyce saw âhundreds of wooden cases, most of which contain provisions' around the hut.

4

Mackintosh's first impression was on the neatness of the area. He noted there were little compact heaps of store cases surrounding the hut itself â sledges, snow houses, huts â and âelectrical wire like cast off spider's webs seemed to litter the place'.

5

The Cape Evans hut would be their main base, especially over the winter months of 1915 and for the months from July 1916 to January 1917.

On the voyage to Antarctica from Australia, Mackintosh had worked out his programme. The first season's depot-laying would be carried out in the months of February and March of 1915 and the second and main season of sledging would be from October 1915 to March 1916.

For the first season he planned for teams to take provisions from the

Aurora

to Hut Point, and then onto the Barrier further south from there. The depots on the Barrier would start with one called Safety Camp, at the start of the Barrier, about 20 miles from Hut Point. Then three smaller depots would be laid, which would be called Cope No. 1, 2 and 3 depots. These would end up being approximately 25, 32 and 40 miles south of Hut Point. The next depot would be a large one at Minna Bluff, location 79°S, 70 miles out. The last depot to be laid in the first season would be at 80°S, 140 miles to the south of Hut Point.

In the second season Mackintosh planned for teams to restock the depots laid in the first season, particularly the Minna Bluff depot, and then place new depots out to 81°S, 82°S and 83°S, with the final one at Mount Hope at 83° 30´S, 360 miles from Hut Point.

On 24 January, stores were on the decks ready to be unloaded so that Mackintosh could arrange for sledging to start immediately. He did not allow any time for the men or the dogs to become fit for travel because he was already a month behind the timetable Shackleton had set for him: âSail from Hobart about 1st Dec or in sufficient time to enable you to reach McMurdo Sound about the 1st of January'.

6

Sledging was to be conducted by parties of three men. Mackintosh would be in charge of one team, Joyce another, and these two teams would carry out the bulk of the sledging in the first two months. Two other teams would

lay depots close to Hut Point while Mackintosh and Joyce's teams were placing depots further out on the Barrier. Stenhouse would remain on the

Aurora

and be in command of the ship.

Gold-titled and embossed leather-bound diaries were distributed, but Joyce commenced his note-taking by writing on loose-leaf pages, waiting until October 1915 before using his diary. In his first entry, on 24 January 1915, he records his disagreement with two of Mackintosh's decisions â both would have serious ramifications later on. The first was Mackintosh's plan to use the dogs for hauling sledges before they were fit. The second was not sending the ship back to New Zealand for the winter.

Richards later wrote that at this stage of the expedition Mackintosh was in charge and Joyce loyally obeyed his instructions.

7

But Joyce was the most experienced and expected some weight to be attached to his views. In his note he clearly felt that the dogs were not acclimatised (owing to the small amount of space they had had for exercising on the ship and the continual soakings they had from the sea water). However, Mackintosh was determined to have a depot laid at 80°S before winter so he decided to take the dogs sledging straight away.

Joyce was back in familiar territory, working around Hut Point, Observation Hill and Cape Armitage at the base of McMurdo Sound as he had in this area with Scott in 1901â04 and with Shackleton in 1907â09. Joyce's main concern was the thickness of the sea-ice between Hut Point and the Ice Barrier to the south.

The dogs were clearly an important part of Joyce's Antarctic life. Throughout his diary he made constant reference to them; how they prevented the men feeling lonely, how the dogs were always pleased to see the men and how he felt for them when they were short of food or dying.

Joyce starts his diary notes. (He occasionally used verbose or flowery phrases, for example, here he uses the term âthe inner man' â meaning he fed himself and the other men.)

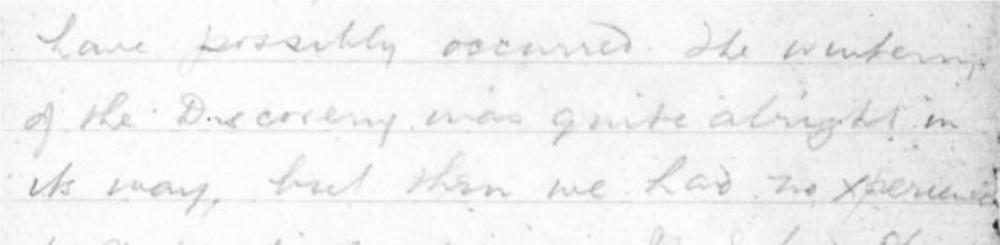

Joyce:

Sledging Jan 24

Â

Jan 24. After breakfast Skipper + I discussed several details. I could not get him to see that we were jeopardizing the dogs + I cannot quite understand why Shacks should alter his plan of campaign. As for wintering the ship â this to my mind is the silliest damn rot that could have possibly occurred. The wintering of the

Discovery

was quite alright in its way, but then we had no experience of Antarctic conditions. If I had Shacks here I would make him see my way of arguing.

Anyway Mack is my Boss + I must uphold him until I find that he is not fit to carry out the hard tedious work that is in front of us. Having one eye will play merry hell with him in the extreme temperatures. As he will not take my advice about the dogs I must let him have his way.

I gave a lecture to the parties on sledging. With the exception of Mack who accompanied me on a short journey in 1909 no one has any experience. I related to them some experience, advising them on different subjects such as avalanches, frostbite, snow blindness etc.

As I am laying the course to the Bluff I am marking same by cairns + flags as one is liable to find crevasses. As this is my 7th journey to the Bluff my experience will help them through.

After lunch packed sledge on the ice â the weight over 1200 lbs. Harnessed the dog team after a struggle they wanted to get right away. Their names are Nigger (leader), Dasher, Tug, Pat, Briton, Scotty and Hector. The average weight of the team about 80 lbs â a good heafty lot. My sledging mates are Gaze + Jack.

With many cheers we proceeded on our course south.

Arrived at Hut Point about 5 o'clock.

Tethered the dogs and viewed the sea-ice from Observation Hill. The ice around Cape Armitage seems very thin so will have to steer well out.

Fed the dogs + then the inner man. Turned in early in readiness for an early start in the morning.

During the night heard the dogs barking. On going out to find the cause â found some of them adrift. They had bitten through their harness. Were in a fighting mood, and before I could separate them one was killed. Unfortunately they have

very sharp teeth + I suppose they have some old time feud to settle. Moral â see them properly secured.

I have seen one big dog fight here in about the same spot in 1902 when several were killed before we could get to them. This breed of dog requires studying â with the wolf strain they are almost human in their likes + dislikes.

8

The dogs were given no shelter, but simply tied up by chains, suitably spaced, to a long steel cable, giving them a radius of movement of a few yards. They were usually very eager for work, and rushed up to the men and tried to insert their heads into the loop of harness being carried. The men noticed that dogs lived by incident; monotony was a dearth to them. After a night's sleeping they would watch the tent as the men were making arrangements to start, yelping all the time at their companions with a general eagerness to be off. They would gallop gloriously for the first half-mile or so, when the sledge seemed to weigh nothing to them, but then the excitement began to pall, especially if there was nothing ahead to see, or smell. One man would often walk ahead when the going was very heavy, which would raise the spirits of the dogs â they would have something to see. If they saw a mirage up ahead the dogs would cock their ears and their footsteps would quicken. The men thought the dogs would see the mirage as a penguin or a seal.

9

Mackintosh had been keeping a daily log, but his first diary note in Antarctica, on 24 January 1915, describes the dogs of Joyce's team as they left the ship for Hut Point. Wild starts his diary when he and a few men from the

Aurora

skied across the sea-ice to Hut Point. His dry sense of humour comes through as he describes the destination not being any closer after each hour's skiing. In his laconic way, Wild explained what happened

when they reached the hut, with a backhanded compliment to the two Scotsmen in his group.

Mackintosh:

Nigger made a splendid leader and as soon as he was traced on the sledge, was all ready, legs spread out in the orthodox fashion ⦠when once the order was given to start they made a wild dash, ran into each other and furiously bit their partners which brought the sledge to a standstill.

Another try was then made after adjusting the tangle they had put themselves into. The method was then tried of each man leading a dog, which went well at first: but again, a bundle of dogs fighting in their keenness to be off again occurred.

A third & fourth try and then at last with three men sitting on the sledge they went off fairly respectfully. A parting shout and three cheers, and they gradually were specks in the distance.

10

Wild:

I must go back to Hobart now. We got the dogs ashore there on 31st of Oct 14. Ninnis & I stopped there with them until the ship came round from Sydney. We made a rough sledge & used to exercise the dogs whenever possible making three good teams. The ship came to Hobart on the 20th December & we went aboard with the dogs on the 24th. The Aurora leaving on the same day calling at Macquarie Island on the 29th to land stores. I went ashore & shot three seals for dog meat. We killed our first penguin there & had some of it for dinner. Everyone pronounced it excellent.

Since then, up to now, we have been trying to get to Hut Point. A party of six, myself included, left the ship last Monday to go to Hut Point. We went on ski & took a sledge with tent, food, etc. It took us eight & a half hours to get there & the last five hours it was only half a mile away at the end of every hour. The Skipper said it was 12 miles but we reckoned it was twenty.

Two others in the party fell into a crack in the ice and got wet feet and legs and a third fell into the water up to his neck, shivering so much when he got out that it made them all shiver so they dashed to the hut at Hut Point.

There was a blubber stove in there so we lit it & put some blubber on, drove everybody except Stenhouse & Stevens out; they are Scotch so they could stick

it. There were only two sleeping bags there, so we had to take it in turns to have a sleep. It was too cold anywhere else. That was my first sledging experience.

11

The first team led by Joyce had departed on 24 January. The second sledging party of Mackintosh, Spencer-Smith and Wild, with a team of nine dogs, left the ship on 25 January, also aiming for Hut Point. These three men shared the one tent, cooked, and travelled together for the vast majority of their sledging. There was no explanation from Mackintosh as to why he chose Spencer-Smith and Wild to be in his team.

Spencer-Smith's first diary note was made that night, 25 January. It was after his initial foray into sledging, but he had no complaints.

Wild made a few notes that evening. He mentions âOates', who was Captain Lawrence Oates, a member of Scott's polar party. He had frostbitten feet and was unable to keep up with the others on their return journey. He is best known for sacrificing himself with the words âjust going outside and may be some time', found within Scott's journal. The date was 17 March 1912 and Oates was also born on 17 March, in 1880. In a remarkable coincidence, Spencer-Smith too was born on this date, in 1883.

The sledge for each three-man party carried their equipment (tent, sleeping bags, etc.), their own food requirements and provisions that had to be left at depots for Shackleton. In his diary Wild listed the equipment they carried on each sledge for the three-man team.