Shackleton's Heroes (3 page)

Read Shackleton's Heroes Online

Authors: Wilson McOrist

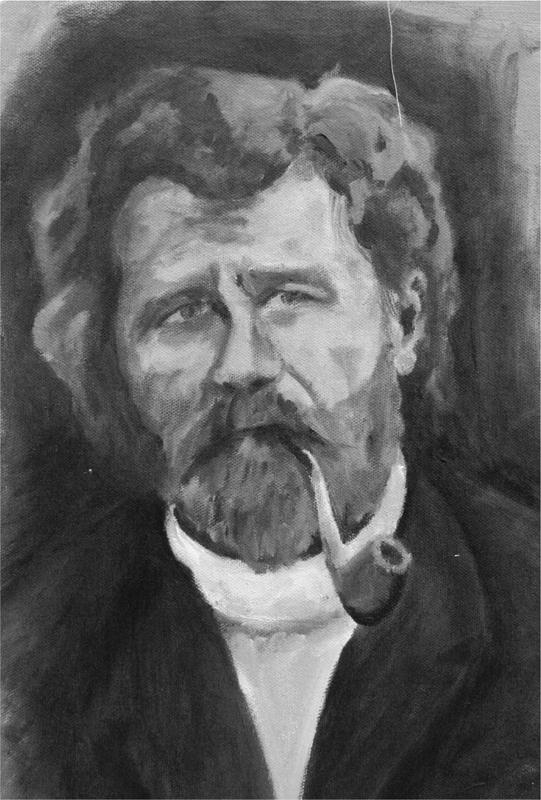

- Joyce was the oldest member of the Mount Hope Party, and the man with the most experience in Antarctica. He was a short, stocky man, only 5 ft 7½ in. in height, with dark brown hair, blue eyes, a tattoo on his left forearm and a scar on his right cheek.

- His naval records show that he was born at Feltham, Sussex in southern England in 1875, making him four years older than Mackintosh. Joyce's father was a former naval rating and after his father's death, Joyce was sent to the Greenwich Royal Hospital School in London, founded in

1712 to educate boys for service in the Royal Navy. (Unlike the Merchant Navy, in which Mackintosh was employed, the Royal Navy is a branch of the British armed forces.)

- His naval records also disclose that, as a twelve-year-old, he joined the navy as a Boy 2nd Class Seaman, on the ship

St Vincent

, in 1891. From 1891 to 1901 Joyce progressed through the ranks as an Ordinary Seaman to Able Seaman, gaining a character rating of âVery Good' on many of his reports.

17

- In 1901 Joyce was serving on HMS

Gibraltar

at Simon's Town, Cape Town in South Africa when Scott's expedition ship

Discovery

stopped there on the way to the Antarctic. He was chosen to join the

Discovery

Expedition and on this trip Joyce was allocated tasks that were to stand him in good stead for his work as a member of the Mount Hope Party. He assisted in the laying of the supply depots, gaining experience in sledging, dog-driving and Antarctic conditions, but he suffered severely from frostbite. In September of 1903 the mercury in the thermometer sank to below -67° F when Joyce was out on the Barrier. He found one of his feet white to the ankle and it took over an hour before his tent-mates could get any sign of life in his foot, by taking it in turns âto nurse the frozen member in their breasts'.

18

Joyce was promoted to Petty Officer 1st Class on 10 September 1904 in recognition of his service in the

Discovery

Expedition.

19

- In 1907 he was discharged from the Royal Navy to form one of the crew of the

Nimrod

on Shackleton's 1907 expedition to Antarctica. On this expedition we learn from Shackleton of Joyce's fondness for dogs. He tells us Joyce enjoyed running them when on-shore, giving them steaming hot feeds and working at training them to pull a sledge.

20

To the other men on the

Nimrod

Expedition Joyce âhad charge of them, fed them, and taught them sledging'.

21

We will see from Joyce's Mount Hope diary records that he realises the value of dogs. Joyce was not chosen to be on Shackleton's main southbound party â he had suffered badly

from frostbite and the doctor (Marshall) diagnosed a damaged liver due to excess drinking, and a weak heart.

22

However, he was a member of a support party that initially accompanied the southern team and he led a team to lay supplies at Minna Bluff for the return of the southern party. In late February 1909, Shackleton's party was struggling back north towards this Minna Bluff depot, after turning back less than 100 miles from the South Pole. Shackleton tells us that they were at the end of their supplies, except for some scraps of meat scraped off the bones of one of their horses that died on the trek south. Shackleton had faith in Joyce and had no doubt that the Bluff depot would have been laid correctly because, in his words, âJoyce knows his work well'.

23

- Joyce did not return to the Royal Navy after the

Nimrod

Expedition but worked in Australia, at one time managing a lodging house in Kent Street, Sydney.

24

He gained some notoriety in 1911 when he was charged with assaulting a policeman but a testimonial from Shackleton was read to the court which, a newspaper claimed, stated that Joyce bore an excellent character.

25

- Joyce's written notes on the Mount Hope Party are in three documents. There is his original blubber-oil-stained field diary where he recorded what happened during and at the end of each day. He rarely misses a daily entry from January 1915 until May 1916 and this field diary forms the bulk of Joyce's words that are included here. He writes short cryptic notes and he is very straightforward with his opinion of people, particularly in naming those who, in his eyes, are malingering or not contributing. We see the picture as it was for Joyce, warts and all. He clearly did not expect this field diary to be used by others because he created a second set of notes, a transcript of his field diary that he made with Richards's help, when recuperating at Cape Evans at the end of the expedition. Many of the harsher criticisms of the other men are not carried forward into the transcripts and only a handful of transcript notes are reproduced here. Finally we have Joyce's book,

The South Polar Trail

. The book is excellent from the point of providing us with a day-by-day account

of the expedition, but it differs in too many ways from his actual field diary to be of more than a limited value. His field diary notes reproduced here are as they appear in his diary, even though there are many sentences with no structure and sometimes only a few words are used to explain an event. His grammar is often non-existent and there are spelling mistakes. He uses words like âweigh' and âshew' which, until the 1920s, were not considered as incorrect spelling. He uses symbols, such as âS' for Mackintosh (the Skipper) and abbreviations like âProvi' for âProvidence'. This is understandable, however, when one considers Joyce's education and the situation he was in. Like all the men, he was usually writing up his diary in miserable circumstances; sometimes in the dark, in his sleeping bag, in a tent, in freezing conditions and after a day's work hauling a sledge.

- His portrait, taken from a photograph after Joyce had returned from Antarctica, shows a rugged weather-beaten face, a shock of hair, and beard. He appears to have an almost quizzical look in his eye, or possibly a disdain for someone in higher authority; a character trait that surfaces many times in his diary concerning his relationship with Mackintosh.

- Harry Ernest Wild was a navy man, serving an uninterrupted twenty years on ships before joining Shackleton's expedition in 1914. He was born in 1879 at Nettleton, Lincolnshire in England, the third son of Mary and Benjamin Wild and one of thirteen children.

26

27

In 1885 the Wild family moved to Eversholt in Bedfordshire, a tiny village which even today consists of little more than a small number of homes, a cricket green, the St John the Baptist church and a pub, The Green Man. As a boy, Ernest was in the church choir. Later he reputedly developed a good tenor voice and became known as a person who could sing a comic

song heartily.

28

From diary records of the Mount Hope Party it appears that Ernest Wild's singing helped maintain the good spirits of his tent-mates at crucial times.

- His brother was Frank Wild, who had been on the

Discovery

and the

Nimrod

expeditions and he was Shackleton's second in command on the

Endurance

Expedition.

- In 1894, at fifteen years of age, Wild entered the Royal Navy and his naval records show he was barely 5 ft tall at that time, and that he only grew another 3 inches. He started as a Boy 2nd Class in HMS

Boscawen

, a boys' training ship at Portland. He served with a number of ships, advancing to Able Seaman on 1 May 1898, still aged only eighteen. Like Joyce, Wild was stationed in South Africa in 1901 when Scott's HMS

Discovery

called at Simon's Town. In 1905 Wild was promoted to Petty Officer 1st Class.

29

His naval service record shows that he was awarded a Good Conduct badge in 1904, which was taken from him a year later, but restored in 1906. This process was repeated in 1909, then again in 1911, showing a character trait that personnel at the Naval Historical Branch have described as âWild by name, wild by nature'.

30

- Wild's diary entries vary considerably in length. At times he obviously felt predisposed to write and he pens paragraph after paragraph describing what had gone on over the previous few days, or weeks. At other times he would hardly make a diary entry for a month, apart from a very brief note with no more than a sentence or two to mention one feature of his day. He was the only man of the Mount Hope Party to write with any humour. Others mention occasional events that make them laugh or that they found amusing, but Wild seemed to have the ability to look at the lighter side of life when writing up his diary notes. This was even after struggling all day hauling a heavy sledge, lying in the tent eking out diminishing food rations, or when he had severe frostbite in his toes â even when he was in a life-threatening situation. Wild was very direct in what he wrote and was not afraid to say what he thought, particularly in

regard to Mackintosh's behaviour. He was a navy man of many years but Wild did not swear in his diary at all, the closest being when he would write âh__l' and âd___d' for âhell' and âdamned'.

- His nickname was âTubby', which had come about because he was short and looked heavy. He became the most popular man of the Mount Hope Party team, seen by Richards and the others as âan uncomplicated soul, always cheery and willing to help at all times'.

31

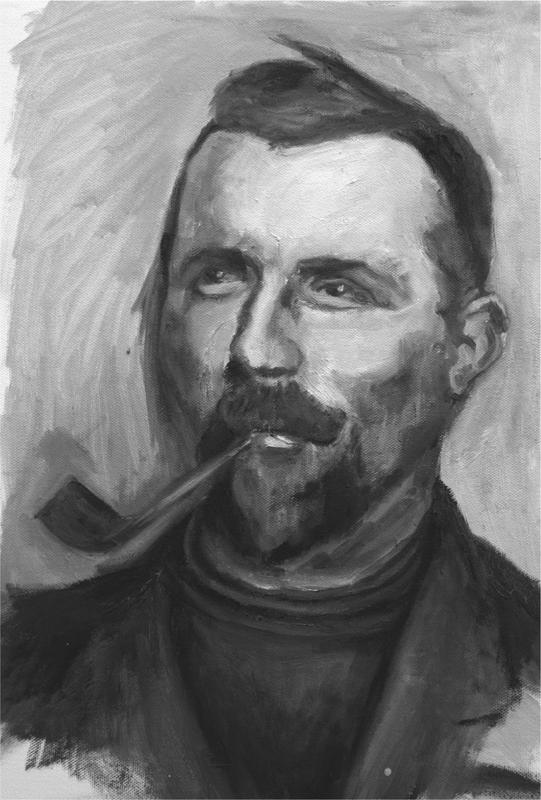

- The portrait of Wild is from a photo taken after his rescue, on the

Aurora

returning to New Zealand. Knowing through his diary how much Wild misses his âbacco' on the Mount Hope journey, one can almost feel the happiness and contentment emanating from his face as he smokes his pipe.

- Arnold Patrick (called A. P., âSmithy' or âPadre' by the other men) Spencer-Smith was born at Streatham, London on 17 March 1883. He was one of seven children.

32

When he was thirteen his father Charles applied for Arnold to be admitted to a boys' boarding school, Woodbridge Grammar School in Suffolk. Arnold studied classics at Woodbridge for six years, and the school magazine shows that he was also much involved in sport, excelling in cricket, football, fives and gymnastics. His later interest in travelling to Antarctica may have been kindled at an 1899 school lecture given by a W. W. Mumford on âArctic Travel and Adventure'. The lecture touched on the travels of explorers in the Arctic regions, some who

perished in their attempts to reach the North Pole and others who lost their lives searching for the North-West Passage. Spencer-Smith wrote a report of the lecture for his school magazine.

33

- He passed First Class London University Matriculation Examinations and then attended King's College, London and Queen's College, Cambridge where he read history. In 1907 Spencer-Smith was appointed Master at Merchiston Castle Preparatory School, Edinburgh, a boys' boarding school, where he taught French and mathematics. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Historical Society in 1913 and ordained as an Anglican priest five days before he left London for Antarctica.

34

- Spencer-Smith's character and occupation as a priest come out in his diary. He clearly enjoys friendly discussions and arguments, singing hymns at times of celebration (Mid-Winter's Day, for example) and reading. There are many Latin quotes, references to sermons and almost daily quotes from the Bible. He tells us of the hard graft of man-hauling, of running low on food and of his faltering health, but there is no trace of bitterness, no complaint and no person is blamed. He writes up his diary almost every day, often musing on his dreams or events of his past. When facing the possibility of dying, he remains positive and is confident that all will be well at the end â his strength appears to come from his faith in God. He writes a wonderfully eloquent diary.

- In all group photographs of the Mount Hope men Spencer-Smith stands out. He was the tallest man in the party; around 6 ft 4 in. in height, and, unlike the other men, he was of slim build. When he was a student at Queen's College in Cambridge, an article described him as âslight but bony'. Another article gives us a clearer picture of the man: âHis lithe and lengthy form, studious stoop, pallid brow, neatly-groomed head, mediaeval raiment, decadent pumps, and inevitable Woodbine,

*

are familiar in the courts (of the College). It has been said that he has charming manners.'

35

Other books

Three Little Words by Susan Mallery

The Dictator by Robert Harris

A Dangerous Deceit by Marjorie Eccles

Catalyst (A Grace Murphy Novella) by Hamlett, Nicole

Vampire in Chaos by Dale Mayer

Hidden Riches by Nora Roberts

Meant to Be by Jessica James

The Goblin Gate by Hilari Bell

Losing My Balance (Fenbrook Academy #1.5) by Helena Newbury

Heirs of the Blade by Adrian Tchaikovsky