Read Sex Cells: The Medical Market for Eggs and Sperm Online

Authors: Rene Almeling

Tags: #Sociology, #Social Science, #Medical, #Economics, #Reproductive Medicine & Technology, #Marriage & Family, #General, #Business & Economics

Sex Cells: The Medical Market for Eggs and Sperm (25 page)

Susan, a twenty-four-year-old with a young son, had donated twice through Gametes Inc. She described the offspring from her donation

.

This is not my baby, because she [the recipient] nourishes this baby for nine months. There’s an egg and there’s a sperm, which create a child, but everything that goes into her body is put into this child’s body. She’s making everything to do with this child. This baby is not mine.

Olivia, a four-time donor at Creative Beginnings, was about the same age as Susan but had no children. She explained how her friends reacted to her decision to become a donor

.

My friends thought I was crazy. They were like, “What are you doing? Technically, if a baby is born, that’s your baby.” And I just thought, “No.” I mean, it might have my physical characteristics, or it might have my genetics, but I’m not the one bearing that child. I’m not the one going to the hospital every couple of weeks to make sure the pregnancy is going well. I’m not the one that’s going to be there when the child is born. I’m not the one taking care of the child once it is born.

Erica, a twenty-seven-year-old two-time donor at Gametes Inc., references her experience as a mother of two young children in explaining why she is not the mother to offspring from her donation

.

As a mother, I can’t imagine carrying a child and giving birth to it and holding it and then giving it to someone else. Even though the eggs obviously carry a ton of genetic information, it’s still just an egg. There’s no heart, no brain. It’s not like it’s anything you bonded with or chose not to bond with.

Megan, a twenty-two-year-old who plans to have children in the future, had recently donated for the first time through Creative Beginnings. She responded to a question about the difference between the offspring and the children she plans to have someday

.

The difference between me being a mother one day and realistically already having offspring in the world is going to be a big difference, because I will have no influence whatsoever on that offspring. That’s really a complicated question. From day one, I am responsible, me and my future husband, who doesn’t exist right now [

laughs

]. We will together be responsible for a child. I feel like my influence is what’s going to be the big part of making an offspring from my own body mine, whereas I can donate, and there could be an offspring of my genetic makeup out there, but it’s not mine, because I’ve had no part in its being raised or even in its conception. I mean the conception happened, and I wasn’t there for it [

laughs

], and that’s a big part of it. If I’m not there for any of the growth process, I feel like there’s no tie there. Whatever person this baby becomes, it’ll all depend on what its parents were like, not necessarily on genetic makeup. But my own child, I would be there for everything. I don’t have that sense of mine when it comes to the baby that they will be having. I don’t feel a connection.

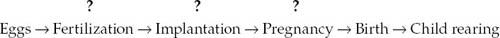

Not only do women point to more stages in reproduction, they are also more likely to refer to each stage as contingent, as possible but not

inevitable. Egg donors are more likely than sperm donors to specify their donation as eggs, which are mixed with sperm, which

might

result in the creation of embryos, which

might

implant in another woman’s uterus, which

might

result in a successful pregnancy, which

might

result in the birth of a child.

16

For egg donors, then, reproduction looks like this:

Men, who hear less about recipients, draw a more direct line from sperm to baby and assign much less uncertainty to the process. For sperm donors, reproduction looks like this:

Sperm → Baby

In part, these views, which are held by donors at different stages in life and living in different parts of the country, are shaped by donation program protocols. At egg agencies and sperm banks, staffers draw on cultural norms of maternal femininity and paternal masculinity to recruit and market donors, but they do not actually want donors to see themselves as mothers and fathers. (This could lead to complicated and messy battles over custody, which has occasionally occurred in the realm of surrogate motherhood.) But it remains a distinct possibility, given that women and men are providing genetic material in a society that defines biological ties as significant and familial.

17

So while the last thing most donors would want is to be responsible for offspring, staffers take precautions to ensure that this does not happen, from requiring donors to sign contracts giving up all parental rights to insisting that all parties to the donation remain relatively anonymous. For example, sperm banks require that offspring be at least eighteen before receiving identifying information about the donor. Egg agency staffers are less adamant about anonymity, but they spend a lot of time coaching women about how to conceptualize their relationship to offspring, insisting that women are “just” providing eggs, not becoming mothers. Beth, a six-time donor who now works at OvaCorp, called it a “main focus. [The agency] and the psychologist really want to make sure

you understand what happens afterwards, that you understand that this is not your child, that you know what you’re getting into, and that it won’t really bother you years later. It’s an egg, and you drop an egg every month with your menstrual cycle.”

In looking at the underlying causes of the donors’ views and the staffs’ protocols, it appears that both are referencing age-old beliefs about the role of men and women in procreation. From the time of the ancient Greeks, there has been a long tradition of identifying the male contribution as primary, a view of reproduction in which men provide the generative seed and women provide the nurturing soil.

18

Noting this distinction, anthropologist Carol Delaney makes the argument that maternity and paternity are not purely physical relationships. Instead, she believes they are “concepts” that cannot be abstracted from the cultural systems in which they are made meaningful. She writes that in the West,

Paternity is not the semantic equivalent of maternity. Traditionally, even the physiological contribution to the child was coded differently for men and women, and therefore their connexion to the child was imagined as different. Maternity has meant giving nurture and giving birth. Paternity has meant the primary, essential, and creative role.

19

Sperm donors who draw a short line from sperm to baby and sperm banks that institutionalize identity-release programs are referencing just this view of paternity, pointing to the man’s contribution as crucial in shaping who the child becomes. Likewise, egg donors and egg agencies mobilize this view of maternity, de-emphasizing the importance of the egg in favor of highlighting the gestational or caregiving components and pointing to the recipient as the “real” mother, the one who nurtures.

One corollary to the view that fathers are creators and mothers are nurturers is that men who do not nurture are still fathers, yet women who do not nurture are censured as bad mothers. Emotionally distant fathers, absent fathers, and other “deadbeat dads” may not be held in the highest regard, but they are still fathers. In contrast, there is enormous cultural pressure on women to practice what Sharon Hays calls “intensive mothering.” Those women who do not nurture their children, and

particularly those who are distant or absent, violate the cultural expectation of maternal instinct and are considered nothing less than unnatural.

20

For this reason, egg agencies and egg donors both have a powerful incentive to define egg donors as not-mothers. If egg donors were categorized as mothers, then, culturally speaking, they would be the worst kind of mothers. Not only are they not nurturing their children, they are selling them for $5,000 and never looking back.

CONCLUSION

It turns out that the former president of ASRM quoted at the beginning of this chapter was right: egg and sperm donors have very different understandings of their relationship to offspring but not quite in the way he expected. Men do “give a hoot,” considering the provision of sperm to be essential in defining who is a father. Women, who do not show any signs of slavishly responding to some internal maternal instinct, believe that there are too many intervening stages between the eggs they provide and the babies that result to consider themselves mothers.

These conceptualizations are buttressed by organizational practices. The gift rhetoric in egg agencies serves to highlight the importance of what the egg donor is doing for the

recipient

, making it possible for

her

to have a child and become a mother. In contrast, the identity-release programs in sperm banks work to underscore the significance of the

donor’s

genetic contribution, making it difficult for men to

not

think of themselves as integral in the lives of offspring.

Egg and sperm donors’ orientations to offspring are also profoundly shaped by cultural depictions of motherhood and fatherhood in twenty- first-century America, depictions with deep roots in Western philosophical and medical traditions that are given a modern spin in the realm of assisted reproduction. The elements of maternity are separable, which makes it possible to associate (or not associate) genetics, gestation, and caregiving with motherhood. In contrast, the elements of paternity are not so easily partitioned; the sperm provider is still a father of some sort.

Indeed, this study reveals that the distinction between biological and social parenthood is gendered. Women and men must rely on gender-specific versions of this distinction, and, as a result, egg and sperm donors can construct different definitions of their connection to offspring. Men cannot help but see themselves as fathers, because they are providing sperm in a culture that equates male genetics with parenthood. Women can define themselves as not-mothers, because they are providing eggs in a culture in which it is possible to separate female genetics from parenthood. This is more than just a possibility for egg donors, though; it is a necessity given the censure of “bad mothers.”

People who donate eggs and sperm say that one of the questions they hear most often is “What does it feel like to have kids running around out there?” The fact is women and men will answer this question in different ways. It is not that egg donors feel no connection whatsoever. Like sperm donors, they are willing to meet with offspring in the future and are even curious to see who they become. But for women, the defining connection is with recipients, not offspring. The opposite is true of sperm donors, who feel little connection to recipients but experience a defining connection to offspring.

Conclusion

As the technologies of artificial insemination and

in vitro

fertilization rendered eggs and sperm transferable from donor to recipient, markets developed for these bodily goods. In the earliest sperm donation programs, physicians organized donation as a quick task to be performed in exchange for cash, yet those running the first egg donation programs constructed the exchange as a gift from caring donor to grateful recipient. For most of the twentieth century, physicians retained control over the process of selecting donors, but in the late 1980s, they began to cede this task to commercial agencies. In sperm donation, this was a result of logistical difficulties associated with the transition to frozen sperm in the wake of the AIDS epidemic. In egg donation, physicians could not keep up with the rising demand as IVF with donor eggs became increasingly popular. However, even as the market expanded, the gendered

understandings of donation originally mobilized by these physicians continued to appear in new and different organizational contexts: donation programs located in different parts of the country and driven by different missions, including feminist nonprofits, university clinics, and commercial agencies.

Venturing inside these contemporary programs, talking with staff, and hearing from donors reveals the myriad ways in which framing donation as a gift or a job influences day-to-day practices. At every stage of the donation process, egg agencies emphasize the connection between donor and recipient. Eggs cannot yet be frozen (unlike sperm), so an egg donor will cycle with “her” recipient, which lends a sense of camaraderie even if they never meet. In contrast, sperm bank staffers rarely mention recipients, and men produce samples that are stored for six months before being shipped all over the world. Donation programs pay women more than men because of the different levels of risk associated with IVF and masturbation, but this confluence of biology and technology does not explain why women receive a negotiated sum regardless of bodily performance and men receive standardized payments doled out every two weeks.