Sex Cells: The Medical Market for Eggs and Sperm (18 page)

Read Sex Cells: The Medical Market for Eggs and Sperm Online

Authors: Rene Almeling

Tags: #Sociology, #Social Science, #Medical, #Economics, #Reproductive Medicine & Technology, #Marriage & Family, #General, #Business & Economics

Looking for jobs on [the website] Craigslist once a month, maybe twice a month, [the sperm bank] puts up an ad that says, “Making money never felt so good.”[

laughs

] It’s really corny. I kept seeing it, and I was really strapped for cash, so I looked into it. [After-school teaching] was only twelve hours a week, $8 an hour. Not enough to live on. I needed to do something else, so I started SAT tutoring. I just applied for a ton of stuff at the same time.

Later in the interview, he filled in a little more detail about what this “ton of stuff” entailed. “At the time, I was trying to get into medical studies. I really needed cash. I was willing to sell my body, anything, sperm, whatever. I was trying to get into a study for opiate addicts. If there was money involved, I would do it. It’s just my body. It’ll heal, whatever they do to it [

laughs

]. It’s a party body.”

About a third of the donors, including Dennis, took care to mention that their monetary interests were not so strong that they felt the need to whitewash their profiles, especially in terms of reporting their family’s health history. Heather, a college student, was worried that she would not be accepted as a donor because her “father died of a heart attack, and so did his parents. I was like, ‘Oh there’s a big negative sign there.’ But I put it down anyways, because if I lie about that sort of thing and then later on down the road this child develops something, I couldn’t lie about that. It’s important. So I would rather have them not pick me up than lie about that.”

For other donors, this impulse only went so far. One of the younger women agreed that it was important to be truthful in regard to family health history but not necessarily in other parts of the profile.

I tried to answer everything [on the profile]. Some of the things, you kind of tell little fibs. How often do you drink? It’s like, come on! [

laughs

] I really wanted a match, and so I said I drink less than I really do. I used to smoke. So I tried to be honest about that, because I thought maybe that would be a concern. [The donor manager] looked at my profile, and she said, “Can you quit? I don’t accept donors that smoke.” I was like, “Okay I’ll quit.” Just little things. Have you ever tried recreational drugs? Hello, who hasn’t?! [

laughs

] But as long as I’m not doing it while I’m in the cycle, then I think it should be okay. The part about my family [history], I had to force the information out of my parents, about when were [relatives] born, when did they die, how much did they weigh. [My parents said,] “Why are you asking all these questions?” [I told them,] “It’s for a project at school.” With all my aunts and uncles, I don’t really know all the diseases and stuff. I know that if somebody had something in my family, my parents would have told me, so with that, of course to the best of my knowledge, I tried to be as truthful as possible.

In another case, an egg donor, who is herself a woman of color, had encouraged several Asian American friends to donate, because she knew they were “in demand.” In response to a question about whether she gave her friends any advice about filling out the profile, she paused before explaining,

Some of my friends were complaining about how they didn’t get matches. I told them, “Just say you’re Chinese.” [

laughs

] Yeah, because I think Asian features, they’re all alike. A lot of couples want pure Chinese, so it kind of sucks. [My friends] want to get matched. They are Chinese, they’re like maybe half Chinese, but they’re still Chinese.

These kinds of reports were not common in the interviews, but the potential for this sort of subterfuge exists, because there is no way of independently verifying most of the information that donors provide on profiles.

“HELPING OTHERS”

About a fifth of the donors started out with a very different motivation: they were primarily interested in helping recipients have children. In comparison to donors who were “in it for the money,” these donors were at a different point in their lives, more likely to be married, to have children, and to be financially comfortable. All five sperm donors in this category were salaried professionals, and all started donating at older ages. The three egg donors were a little more heterogeneous in terms of employment; one was a music teacher, another was a housewife, and the third occasionally worked in part-time clerical positions.

The donors who signed on to help others were also more likely to be close with someone who had experienced infertility. Lisa, a twenty-six-year-old mother of two young children, decided to become a donor when she learned that her mother was using IVF to start a new family. “I have a tubal ligation, and I don’t want any more kids. I figure I’m young, and I’m making good eggs. I might as well give them to somebody who could use them. I’m just kind of a philanthropic person anyway. I like to donate money or clothes or what have you to different organizations. This is just kind of like the ultimate gift you can give to somebody.”

Two donors had experienced infertility in their own marriages. After having three children with her husband, Rosa had a tubal ligation in her early twenties. However, when he died in a car accident, she remarried and went through almost two years of medical procedures to have a child with her new husband. Rosa described flipping through a magazine while waiting for an optometrist’s appointment with her children when an ad “popped up” at her, asking, “Do you want to help a family that can’t have children?” She called the egg agency, and over the course of the next several years, she twice donated eggs and once served as a surrogate mother.

Evincing a similar empathy, Ryan, a forty-year-old engineer whose wife had difficulty conceiving their daughter, decided to switch from being a regular blood donor to being a regular sperm donor.

We knew that [my wife] had some previous problems and maybe couldn’t get pregnant. She did actually get pregnant shortly after we got married, but it was a miscarriage. We tried later and had a little girl. I just started thinking about it, the joy, the loss of our child, and not being able to have a child. I understand what some of these couples might be going through, but I also understood when a miracle does happen. That’s kind of why I decided to do [sperm donation], just to kind of help others. To be honest, the money from the little donation does help out, and we decided we’d use it toward my daughter’s [education fund]. So every check we get, we deposit it into that account.

Being interested in helping recipients does not preclude appreciating the income from donation. Ryan was a well-paid engineer not in need of

the extra cash, but in referring to how he “helps others” while the money “helps out” his family, he suggests a mutualism to donation.

Three of the men are single professionals without children who referenced a slightly different version of “helping”: they wished to make their genes available to recipients as an act of charity. Travis, a thirty-year-old engineer, pointed out that he had a large family filled with relatives who lived long, healthy lives. So he considered giving “amazing genes” to “people who are trying to have kids” as just one of his many philanthropic endeavors alongside blood donation and community service projects. Ben, a twenty-six-year-old software engineer, invokes not only health and longevity, but also intelligence and athleticism.

Ben: I think I have something to contribute. I feel like I’m a very intelligent individual. I come from a family of very bright people, and we’re all athletic. We live very long lives, very healthy. We don’t have any really serious issues until we’re in our eighties and nineties. I thought that I’m just a prime candidate for donating sperm, and I’d like to be charitable. I give a lot of my money to charitable organizations. I really don’t like donating blood. I like to keep that part to myself. Anybody can really do a lot of these things, but not very many people can donate sperm. So I thought that I’d really be adding something to the community if I did that. So that’s really [it]. Because I’m independently wealthy, I’m not interested in the money. I don’t even accept the money that they give. I give it to my brother who’s a postdoc with a wife and kids.

Rene: So, all the way back in high school, what made you respond positively [to the idea of sperm donation]? Was it just you’re smart and you felt like you could contribute this?

Ben: Absolutely. I thought that if there were more people like me in the world, the world would be a little better, not by that much, a tiny, little, hardly significant amount, but I’d have contributed positively. There’s not very many things as an individual to contribute positively, and this was one of them.

Later in the interview, I asked Ben, “Of all the charitable things you could do, why is this important for you?” He replied, “Because I believe

very strongly that our genes are a large part of who we are, and I think I’ve been blessed with a very strong, very good genetic heritage, and I feel like other people should be blessed.”

4

For most men, the sperm bank was nearby, on the way to work or school, so donating did not involve going more than five or ten minutes out of the way. But three of the men who signed on to help others made much longer trips. Scott drove ten miles from work to the bank, saying, “I can round-trip it in forty-five minutes, so it works for a lunch break.” Ryan drove twenty-five miles each way, and Ben commuted an hour each way. Scott and Ryan are also among the longest-serving donors, at thirty and thirty-three months, respectively. This suggests that their commitment to helping people is strong enough to survive not only these lengthy commutes, but also the need to regulate their sexual activities for such a long period of time.

EARNING AND SPENDING

Given that so many donors are motivated by the money, it is important to look closely at what women and men actually earn from paid donation. As noted in

Chapter 2

, commercial egg agencies often pay different rates to different donors, with first-timers receiving around $5,000 per cycle, a number that will generally increase for additional cycles or for women with particularly sought-after characteristics. University-based programs usually pay less, sometimes as little as $2,000 per cycle.

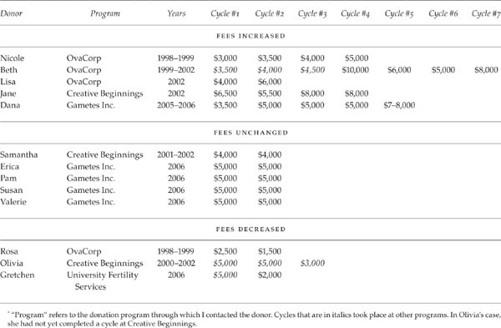

Egg donors reported fees for forty-one cycles that occurred between 1998 and 2006. The fees ranged from $2,000 to $10,000 per cycle with an average payment of $4,297. Of the thirteen women who had donated more than once, five were paid more for additional cycles, five were paid the same, and three were paid less (see

Table 3

).

5

Women in metropolitan areas occasionally donated through multiple programs, which explains some of the variation in compensation (cycles at programs other than those where I did research are italicized in the table).

In each of the commercial agencies, there was at least one woman whose fee increased, though it was less common at Gametes Inc., where staff does not routinely offer higher fees. In Samantha’s case, Creative Beginnings does generally pay more, but she donated a second time to a couple who did not become pregnant the first time, so this may have prevented staff from asking for a higher fee. Of those whose fees declined, Rosa’s second cycle was cancelled before the egg retrieval, so she was only given a partial fee. Olivia donated through two commercial agencies before signing on with a university program, which paid less per cycle. Gretchen donated to a friend before signing up with University Fertility Services, where she was paid $3,000 less, a difference she thought was “logical,” because “if you know somebody, of course they’re going to pay you more.” She was “disappointed” that the university paid so much less.

6

Table 3

Compensation per Cycle for Women Donating Multiple Times*

In most cases, program staffers determine the fee, and egg donors are not always aware of the reasoning involved. For example, Lisa, a twenty-six-year-old, was told by OvaCorp’s donor manager that the “first time around, they usually pay 3,000 [dollars].” So she was surprised when the higher “price” of $4,000 appeared on her first contract in 2002. “For some reason, [the donor manager] asked for more money for me from this first couple. I think it was because I had already had two children and my age. She said I was desirable.” When I asked Lisa what that meant, she responded with a laugh, “Good eggs, I don’t know, good genes.” Likewise, Kim, another OvaCorp donor who was a twenty-three-year-old college graduate, did not know why she was being paid $5,000 for her first cycle but joked, “I’m not going to complain.”

In two cases, the request for a higher fee came from the donor, and it is worth noting that Jane and Dana ended up with some of the highest fees in the sample. Dana did not make this request until her fifth cycle, when she and the Gametes Inc. donor manager decided to ask for $8,000 from the recipients, who countered with $7,000. The negotiation was ongoing at the time of our interview. Like other egg donors, Dana expressed ambivalence about focusing on the money. “I’ve really felt bad about asking for that much. I didn’t want to feel greedy, but at the same time, as much as you have to go through, not only physically but mentally, and the time you have to take away from your job and your family, you really need to be compensated for it.”

7