Send Me Safely Back Again

| Send Me Safely Back Again | |

| Napoleonic War [3] | |

| Adrian Goldsworthy | |

| W (2012) | |

| Rating: | ***** |

| Tags: | Historical, Fiction |

The third novel in the series sees new challenges for the men of the 106th Foot, as the British army attempts to recover from the disaster of Corunna and establish a foothold in the Peninsula.

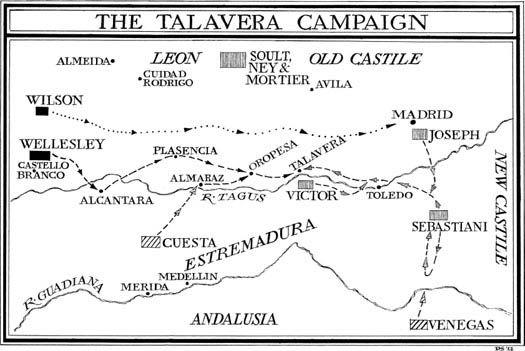

Featuring the battles of Medellin and Talavera, the 106th will have their mettle severely tested on the battlefield. But if Napoleon is to be ejected from Spain, war must also be waged in more covert ways. For Hanley, the former artist who is a more natural observer than fighter, the opportunity to become an 'exploring officer' leads him into even more dangerous territory, the murky world of politics and partisans. And while Ensign Williams seeks to uncover the identity of the mysterious 'Heroine of Saragossa', a conspiracy of revenge within the regiment itself threatens to destroy him before he's even faced a shot from the French.

For Siân

SEND ME SAFELY

BACK AGAIN

Adrian Goldsworthy

Contents

I’m lonesome since I crossed the hill

,

And o’er the moorland sedgy

Such heavy thoughts my heart do fill

,

Since parting with my Betsey

I seek for one as fair and gay

,

But find none to remind me

How sweet the hours I passed away

,

With the girl I left behind me

.

O ne’er shall I forget the night

,

the stars were bright above me

And gently lent their silv’ry light

when first she vowed to love me

But now I’m bound to Brighton camp

kind heaven then pray guide me

And send me safely back again

,

to the girl I left behind me

.

Her golden hair in ringlets fair

,

her eyes like diamonds shining

Her slender waist, her heavenly face

,

that leaves my heart still pining

Ye gods above oh hear my prayer

to my beauteous fair to find me

And send me safely back again

,

to the girl I left behind me

.

The bee shall honey taste no more

,

the dove become a ranger

The falling waters cease to roar

,

ere I shall seek to change her

The vows we made to heav’n above

shall ever cheer and bind me

In constancy to her I love

,

the girl I left behind me

.

‘The Girl I Left Behind Me’ was a common military song and march in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. It is quite possible that both the words and tune are considerably older.

L

ieutenant William Hanley of His Britannic Majesty’s 106th Regiment of Foot looked down at the great battle unfolding before him and knew that he was not wanted. Far more soldiers than he had ever seen in one place were stretched in a long crescent across the wide plain. There were Spanish regiments in white and brown and blue, and half a mile beyond them the darker masses of the French cavalry and foot. There were far more Spanish soldiers.

Hanley decided to draw. A tall man, he perched on the low stump of a shrivelled vine tree and crossed one leg over the other to rest his sketch pad. Soon his right hand was moving quickly across the page, caressing the paper as he shaded to give depth to the tiny lines of soldiers. The limits of his skill no longer frustrated him as once they had done. Hanley had lived in Madrid for years, studying art in the company of other passionate young men who believed themselves to be creative and despised those who were not. In those days his constant failure to capture on canvas the images in his mind enraged him. Now, he could sketch or paint for the sheer pleasure of the act, the old dream of artistic greatness long gone.

The death of Hanley’s father merely confirmed the end of that episode in his life, since his half-brothers had immediately cut the allowance paid to their bastard sibling. Hanley fled the French occupation of Madrid and returned to England with barely a penny to his name. Many years before, when he was just an infant, his father had bought him a commission in the army as a source of income, before such abuses were stamped out. Left

with no alternative, Hanley found that he had to become a real soldier. He still found it difficult to see himself as especially martial, and struggled to understand many of his duties, but at least he no longer tortured himself because he was not a great artist. Indeed, his new life made him surprisingly content.

A thought struck him, and he wrote, ‘The plains before Medellín, 28th March, 1809’ at the top of the page. The picture would be a true record, if nothing else.

A groom glanced at the Englishman and paused as he brushed down a horse with an ornate saddle and lavishly decorated saddlecloth. The man had the very dark skin of an Andalusian, and although he was still young his black hair was streaked with grey and currently covered with dust and loose hair from the white horse. He shook his head in bafflement at the eccentricity of the foreigner.

Hanley nodded amicably to the man and then turned to look behind him at the redcoat standing watching over their own three mules.

‘How is he, Dob?’

‘Sleeping like a baby, sir,’ replied Corporal Dobson, his battered face creased into a smile.

The loud snore that followed lacked any infant-like quality, but confirmed that Hanley’s friend and fellow officer, Ensign Williams, was indeed still asleep. Dobson had fixed his bayonet on to his musket and driven the point into the hard earth. Then he had stretched the shoulders of his greatcoat between its upturned butt and the branch of another stunted vine, giving some shade from the noon sun to the officer as he lay in a shallow hollow to rest. Williams’ wide-brimmed straw hat covered his face.