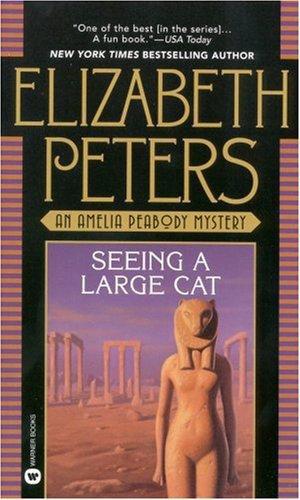

Seeing a Large Cat

Read Seeing a Large Cat Online

Authors: Elizabeth Peters

Tags: #Suspense, #Mystery, #Detective, #Fiction, #General, #Mystery & Detective, #Historical, #Large Type Books, #Mystery & Detective - Women Sleuths, #Fiction - Mystery, #Women Sleuths, #Mystery & Detective - General, #Detective and mystery stories, #Women archaeologists, #Women detectives, #Egypt, #Peabody, #Amelia (Fictitious character), #Historical - General

SEEING A

LARGE CAT

Elizabeth Peters

Book 9

FOREWORD

The Editor is pleased to announce to the world of literary scholarship that there has recently come to light a new collection of Emerson Papers. Unlike Mrs. Emerson's journals, they do not present a connected narrative, but are a motley lot, including letters, fragments of journal entries by persons as yet unidentified, and bits and pieces of manuscript ditto.

It is hoped (by some) that a further search of the mouldering old mansion from which this collection derived may yield additional material, including the missing volumes of Mrs. Emerson's journals. Be that as it may, the present Editor expects to be fully occupied for years to come in sorting, collating, attributing, and producing the definitive commentary on these intriguing fragments. The relevance of many to Mrs. Emerson's journals is at present questionable; it will require intensive textual analysis and travel to faraway places to determine their chronological place in the saga. However, certain sections of what the Editor has designated "Manuscript H" seem to fit into the sequence of the present volume. She is pleased to offer them here.

Chapter One

Husbands do not care to be contradicted. Indeed, I do not know anyone who does.

Really," I said, "Cairo is becoming overrun with tourists these days-and many of them no better than they should be! I am sorry to see so fine a hotel as Shepheard's allowing those male persons to hang about the entrance making eyes at the lady guests. Their behavior is absolutely scandalous."

My husband removed his pipe from his mouth. "The behavior of the dragomen or that of the lady guests? After all, Amelia, this is the twentieth century, and I have often heard you disparage the rigid code of morality insisted upon by Her late Majesty."

"The century is only three years old, Emerson. I have always been a firm believer in equal rights of all kinds, but some of them are of the sort that should only be pursued in private."

We were having tea on the famous terrace of Shepheard's Hotel. The bright November sunlight was only slightly dimmed by the clouds of dust thrown up by the wheels of vehicles and the hooves of donkeys and camels passing along Shari'a Kamel. A pair of giant Montenegrin doormen uniformed in scarlet and white, with pistols thrust through their sashes, were only moderately successful in protecting approaching guests from the importunities of the sellers of fly-whisks, fake scarabs, postal cards, flowers, and figs-and from the dragomen.

Independent tourists often hired one of these individuals to make their travel arrangements and supervise their servants. All of them spoke one or more European languages-after a fashion-and they took great pride in their appearance. Elegant galabeeyahs and intricately wound turbans, or becoming head-cloths of the sort worn by the Beduin, gave them a romantic look that could not but appeal to foreign visitors-especially, from what I had heard, female visitors.

I watched a couple descend from their carriage and approach the stairs. They could only be English; the gentleman sported a monocle and a gold-headed cane, with which he swiped irritably at the ragged merchants crowding around him. The lady's lips were pursed and her nose was high in the air, but as she passed one of the dragomen she gave him a quick glance from under the brim of her flower-trimmed hat and nodded emphatically. He raised his fingers to his bearded lips and smiled at her. It was clear to me, if not to the lady's oblivious husband, that an assignation had been made or confirmed.

"One can hardly blame the ladies for preferring a muscular, well-set-up chap like that one to your average English husband," said Emerson, who had also observed this exchange. "That fellow has all the animation of a walking obelisk. Imagine what he is like in-"

"Emerson!" I exclaimed.

Emerson gave me a broad, unrepentant grin and a look that reminded me-if any reminder had been required-that he is not an average English husband in that or in any other way. Emerson excels in his chosen profession of Egyptology as in his role of devoted spouse. To my fond eyes he looked exactly as he had looked on that long past day when I encountered him in a tomb at Amarna-thick dark hair, blazing blue eyes, a frame as muscular and imposing as that of the dragoman- except for the beard he had eschewed at my request. Its removal had revealed Emerson's strong chin and the dimple or cleft in that chin: a feature that gives his handsome countenance additional distinction. His smile and his intense azure gaze softened me as they always do; but the subject was not one I wished him to pursue in the presence of our adopted daughter (even if I had introduced it myself).

"She has good taste, Aunt Amelia," Nefret said. "He is the best looking of the lot, don't you think?"

When I looked at her I found myself in some sympathy with the horrid Muslim custom of swathing females from head to toe in black veils. She was a remarkably beautiful girl, with red-gold hair and eyes the color of forget-me-nots. I could have dealt with the inevitable consequences of her looks if she had been a properly brought up young English girl, but she had spent the first thirteen years of her life in a remote oasis in the Nubian desert, where she had, not surprisingly, acquired some peculiar notions. We had rescued her and restored her to her inheritance,* and she was dear to us as any daughter. I would not have objected to her peculiar notions quite so much if she had not expressed them so publicly!

"Yes," she went on musingly, "one can understand the appeal of those fellows, so dashing and romantic in their robes and turbans-especially to proper, well-behaved ladies who have led proper, boring lives."

Emerson seldom listens to anything unconnected with Egyptology, his profession and his major passion. However, certain experiences of the past few years had taught him he had better take notice of what Nefret said.

"Romantic be damned," he grunted, taking the pipe from his mouth. "They are only interested in the money and-er other favors given them by those fool females. You have better sense than to be interested in such people, Nefret. I trust you have not found your life proper and boring?"

"With you and Aunt Amelia?" She laughed, throwing up her arms and lifting her face to the sun in a burst of exuberance. "It has been wonderful! Excavating in Egypt every winter, learning new things, always in the company of those dearest to me-you and Aunt Amelia, Ramses and David, and the cat Bastet and-"

"Where the devil is he?" Emerson took out his watch and examined it, scowling. "He ought to have been here two hours ago."

He was referring, not to the cat Bastet, but to our son, Ramses, whom we had not seen for six months. At the end of the previous year's excavation season, I had finally yielded to the entreaties of our friend Sheikh Mohammed. "Let him come to me," the innocent old man had insisted. "I will teach him to ride and shoot and become a leader of men."

The agenda struck me as somewhat unusual, and in the case of Ramses, alarming. Ramses would reach his sixteenth birthday that summer and was, by Muslim standards, a grown man. Those standards, I hardly need say, were not mine. Raising Ramses had converted me to a belief in guardian angels; only supernatural intervention could explain how he had got to his present age without killing himself or being murdered by one of the innumerable people he had offended. In my opinion what he required was to be civilized, not encouraged to develop uncivilized skills at which he was already only too adept. As for the idea of Ramses leading others to follow in his footsteps ... My mind reeled.

However, my objections were overruled by Ramses and his father. My only consolation was that Ramses's friend David was to accompany him. I hoped that this Egyptian lad, who had been virtually adopted by Emerson's younger brother and his wife, would be able to prevent Ramses from killing himself or wrecking the camp.

The most surprising thing of all was that I rather missed the little chap. At first I enjoyed the peace and quiet, but after a while it became boring. No muffled explosions from Ramses's room, no screams from new housemaids who had happened upon one of his mummified mice, no visits from enraged neighbors complaining that Ramses had ruined their hunting by making off with the fox, no arguments with Nefret....

Two men pushed through the crowd and approached the terrace. They were both tall and broad-shouldered, but there the resemblance ended. One was a nice-looking young gentleman wearing a well-cut tweed suit and carrying a walking stick. He had obviously been in Egypt for some tune, since his face was tanned to a handsome walnut brown. His companion wore robes of snowy white and a Beduin headdress that shadowed features of typical Arab form-heavy dark brows, a prominent hawklike nose, and thin lips framed by a rakish black mustache.

One of the giant guards stepped forward as if to question them. A gesture from the Arab made him step back, staring, and the two men proceeded to mount the stairs.

"Well!" I exclaimed. "I don't know what Shepheard's is coming to. They ought not let the dragomen-"

But my sentence was never completed. With a scream of delight Nefret jumped up from her chair and ran, her hat flying from her head, to throw herself at the Beduin. For a few moments the only visible part of her was her red-gold head, as his flowing sleeves wrapped round her slim body.

Emerson, close on Nefret's heels, pulled her away from the Beduin and began vigorously wringing the latter's hand. Nefret turned to the other young man. He held out his hand. Laughing, she pushed it away and hugged him as she had done Ramses.

Ramses? Little chap? Ramses had never been a normal little boy, but there had been times (usually when he was asleep) when he had appeared normal. The sleeping cherub with his mop of sable curls and his little bare feet protruding innocently from under the hem of his white nightgown had become this-this male person with a mustache! I supposed the transformation could not have occurred overnight. In fact, now that I thought about it, I recalled that he had been growing taller year by year, in the usual way. He was almost as tall as his father now, a good six feet in height. I could have dealt with that. But the mustache ...

Trusting that my paralysis would be taken for dignified reticence, I remained in my chair. Emerson had so forgot his usual British reserve as to put an arm round his son's shoulders in order to lead him to me. Ramses's naturally swarthy complexion had been darkened by sun and wind to a shade even browner than that of his young Egyptian friend, and his countenance was as unexpressive as it always was. He bent over me and gave me a dutiful kiss on the cheek.

"Good afternoon, Mother. You are looking well."

"I can't say the same for you," I replied. "That mustache-"

"Not now, Peabody," Emerson interrupted. "Good Gad, this is supposed to be a celebration. The important thing is that they are both back, safe and sound."

"And cursed late," said Nefret, settling herself in the chair David held for her. One of the waiters handed her her hat; she clapped it carelessly onto her head and went on, "Did you miss the early train?"

"No, not at all," David replied. His English was now almost as pure as my own; only when he was excited did a trace of his native Arabic creep in. "The Professor and Aunt Amelia may be getting complaints from some of the passengers, though; the tribe gave us a proper send-off, galloping alongside the train shooting off their rifles. The other people in our compartment fell cowering to the floor and one lady went into hysterics."

Nefret's eyes shone with laughter. "I wish I could have been there. It is so damned-excuse me, Aunt Amelia-it is so unfair! If I had been a boy I could have gone with you. I sup pose I wouldn't have enjoyed spending six months as a Beduin female, though."

"You would not have found it as confining as you may think," David said. "I was surprised at how much freedom the women of the tribe are allowed; in their own camp they do not veil themselves, and they express their opinions with a candor that Aunt Amelia would approve. Though she might not approve of the way in which young unmarried girls express their interest in-" He broke off abruptly, with a sheepish glance at Ramses. The latter's countenance was as imperturbable as ever, but it was not difficult to deduce that he had signaled David-perhaps by kicking him under the table-to refrain from finishing the sentence.

"Well, well," said Emerson. "So why were you so late?"

"We stopped at Meyer and Company, on the Muski," Ramses explained. "David wanted a new suit."

David smiled self-consciously. "Honestly, Aunt Amelia, neither of us has a respectable garment left to our names. I didn't want to embarrass you by appearing improperly dressed."

"Hmph," I said, looking at my son, who looked blandly back at me.

"As if any of us would care!" Nefret exclaimed. "To keep us waiting, fidgeting and worrying for hours, over something so silly!"

"Were you?" Ramses asked.

"Fidgeting and worrying? Not I! It was the Professor and Aunt Amelia. . . ." But her scowl metamorphosed into a dazzling smile; with the graceful, impulsive friendliness that was so integral a part of her nature she held out her hands, one to each lad. "If you must know, I have missed you desperately. And now I see I will have to play chaperone; you are both grown so tall and handsome all the little girls will be making eyes at you."

Ramses, who had enclosed her hand in his, dropped it as if it had become red-hot. "Little girls?"

How often, dear Reader, is a small, seemingly insignificant incident the start of a train of events that builds inexorably to a tragic climax! If Ramses had not chosen to appear in that dashing costume; if Nefret's impulsive welcome had not drawn all eyes to them; if Ramses had not raised his voice in indignant baritone outcry .. . The consequences would draw us into one of the most baffling and bizarre criminal cases we had ever investigated.

On the other hand, it is possible that the same thing would have happened anyhow.

Ramses got himself under control and Nefret wisely refrained from further provocation. She and Ramses were really the best of chums-when they were not squabbling like spoiled infants-and a request from her soothed his temper.

"Can you persuade M. Maspero to let me examine some of the mummies in the museum?" she demanded. "He has been putting me off for days. One would think I had proposed something illegal or shocking."

"He probably was shocked," said David, smiling. "You can't blame him, Nefret; he thinks of ladies as delicate and squeamish."

"I will blame him if I like. He lets Aunt Amelia do anything she wants."

"He's used to her," said Ramses. "We will go there together, you and I and David. He can't resist all three of us. What particular mummies have you in mind?"

"Most particularly, the one we found in Tetisheri's tomb three years ago."

"Good heavens," David said, appearing a trifle shocked himself. "I can see why Maspero . . . Er, that is, you must admit, Nefret, it was a particularly disgusting mummy. Unwrapped, unnamed, bound hand and foot-"

"Buried alive," Nefret finished. She planted both elbows on the table and leaned forward. A lock of gold-red hair had escaped from her upswept coiffure and curled distractingly across her temple; her cheeks were flushed with excitement and her blue eyes shone. An observer might have supposed she was discussing fashions or flirtations. "Or so we assumed. I want to have another look. You see, while you were gadding about in the desert, I was improving my education. I took a course in anatomy last summer."