Secrets of Your Cells: Discovering Your Body's Inner Intelligence (7 page)

Read Secrets of Your Cells: Discovering Your Body's Inner Intelligence Online

Authors: Sondra Barrett

Tags: #Non-Fiction

EXPLORATION

Attune to Your Cellular Sanctuary

Discover the cell’s skills as operating instructions for your own life:

Learn to be in a state of self-creation.

Transform what needs to change.

Grow yourself.

Be fluid and flexible.

Aspire to the sacred within and around you.

Build an altar.

Find sacred space.

You have now begun to get acquainted with the workings of your cells; see how you perform the same actions in everyday living and understand the many levels of sanctuary that can be inspired by reflecting on the cell as a sacred vessel for life. As you continue through this book, each chapter will introduce a new lesson and another architectural feature of your cells. Take your time on this journey and allow your understanding to deepen as you travel. You are a sacred vessel.

Chapter 2

I AM–Recognize

It is an incredible journey from cell to self.

— CHRISTOPHER VAUGHAN

How Life Begins

N

ow that we’ve become acquainted with our cellular sanctuary, in this chapter we explore how our cells “name” themselves. Here we meet many aspects of self: our cellular identification marks, the ways we may personally identify ourselves, how we identify others—even how we can participate in our own self-creation.

It is the job of our psyches to recognize ourselves and others as well as define our boundaries, while our cells do the same physically. Who would have thought our cells could hold such a crucial position? The family of immune cells takes on this essential task, and it is that family we will spend some time getting to know here.

Both cell and self say, “I AM,” and when we fully recognize our cellular and soul connection to the sacred, we may say to ourselves, “I AM THAT I AM.” Many religious traditions, starting with the Jewish people, have written that the name of God is “I AM.” When we fully embrace who we are, when we say, “I AM,” do we resonate with all that is? With all that is holy?

Who Am I? The Way In

When I first started teaching the mysteries of our cells, I asked my students to complete the following statements:

I am . . .

I want . . .

I have . . .

How would you complete the statements

I am . . . I want . . . I have . . . ?

All of these lead to questions people have posed for generations and that we, too, ask ourselves at various times during our lives: “Who am I?” and “Why am I here?” To begin exploring the subject of this chapter, recognizing self as distinct from others, take a few moments to reflect on the many ways you know and define yourself.

You have multiple “markers” of your identity. You have a name, a gender, distinguishing facial features, and a family tree. You have numbers that tag you: A birth date and a social security number link your identity to your “money self,” to banks and other financial institutions and to your employment. These entities have probably assigned you at least one more number—you are employee B7834 or account holder 5483-14-070001. As technology has advanced, you have become further identified by an ever-growing list of numbers and passwords that allow you to gain admittance to the virtual world of the Internet as “you.”

You have your profession or calling, your role in a family, your religious and spiritual inclinations and practices. And if they fit into your belief system, you have an astrological sun sign, a tarot symbol, and perhaps a lucky number. All of these are, or can be, parts of your identity, as are your beliefs and actions.

How

do

you recognize yourself? Is it by what you do in the world? By how people know and react to you? Is your sense of self externally or internally motivated? These are questions to contemplate as you begin to examine the parallels between your own sense of self and the self-identity of the cell. Knowing the self is like cultivating a garden: you

have to be willing to explore the invisible and slow down to nurture your awareness. You need to be willing to work deeper than the surface. For your cells, however, the surface is the key to identity.

“Who am I?” is a question that can be answered by both our cells and our psyches, which together engage in an ongoing conversation to keep us safe. Body and mind share a common responsibility in self-identity, safeguarding us from danger and knowing what to trust. Both detect and protect our boundaries; the body’s immune system, a scientific focus of this chapter on recognizing self and other, determines cellular boundaries and identities, while the nervous system navigates psychological ones.

DEFINITION

Immune,

from the Latin

immunis:

Exempt from public service or charge. Protected. Resistant to a particular infection or toxin owing to the presence of specific antibodies or sensitized white blood cells or relating to the creation of resistance to disease.

The basic job of our immune cells is to recognize “self” and “other” while collaborating with brain, gut, thoughts, beliefs, and hormones. The immune cells are sometimes referred to as a second sensory system, one that sniffs out danger. It is essential to add here that while our genes provide the information for crafting the physical and chemical aspects of our unique identity, our cells reveal those characteristics and our immune cells act on them.

Before we explore the specific activities of immune cells in some depth, let’s take a closer look at cell identity (see

figures 2.1

and

2.2

).

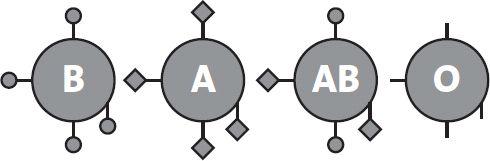

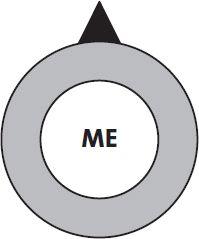

How Our Cells Say, “I AM”

In the architectural design of our cells, the wonderful, fluid exterior membrane that we encountered in the last chapter reveals the cell’s identity. Just as you and I can tell a friend from a stranger by observing a person’s external facial features, our cells do the same; each cell’s “face,” on its outer surface membrane, reveals uniquely identifiable features. Our cellular container is embedded with markings that enable cells to discern one from another. Blips and bumps on the surface are identification codes or passwords that mark “me” or self. These protein “signatures” on the cell membrane, akin to distinctive bar codes, reveal the cell’s identity. These “me” markers also identify the cells as coming from you, a unique individual.

Figure 2.1

Cell as self, “me”

Figure 2.2

Cell as other, “not me”

Like us, each cell has several layers of identity. In addition to “self” markings on the outer edges, cells carry “postmarks” or “zip codes” indicating where the cell originated and what it does: heart cells pump blood; white blood cells protect against intruders; red blood cells carry oxygen to all the tissues, and so on.

Recognizing Self and Other

When cells touch, their identification markings enable them to distinguish “self” from “other.” A reading of “other,” or

not self,

can signal either safety or danger: a threat that must be defended against. In the

bigger picture of survival, “other” may be a threat if it is a pathogenic microorganism. Though it is well established that physical markings, shape, and touch are essential in enabling cells to recognize other cells and molecules, some scientists are now theorizing that molecular vibrations also play a part in recognition.

The way cells recognize differences is often explained with the analogy of a lock-and-key mechanism. The ID signatures on one cell are detected by decoding receptor sites on another cell’s surface; the patterns or shapes of the two cells’ markers fit together like a lock and key. The nature of the fit tells the cell whether what it has brushed up against is safe or not. Immunologists and biochemists have devised analytical methods to distinguish the many surface ID markings on cells, and this has proved highly useful in medicine.

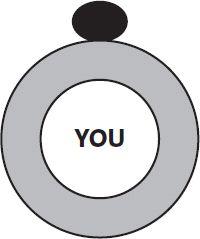

The Medical Uses of Cell Identity

The original clinical use of cell ID markers was for red blood cell typing to ensure safe blood transfusions. Surface molecules on our red blood cells characterize them as either type A, B, AB, or O (see

figure 2.3

), and only like blood types can be safely shared from one body to another. (The exception to this is blood type O, called the universal donor type, since other blood types usually do not detect it as “other.”)