Scent and Subversion (26 page)

Read Scent and Subversion Online

Authors: Barbara Herman

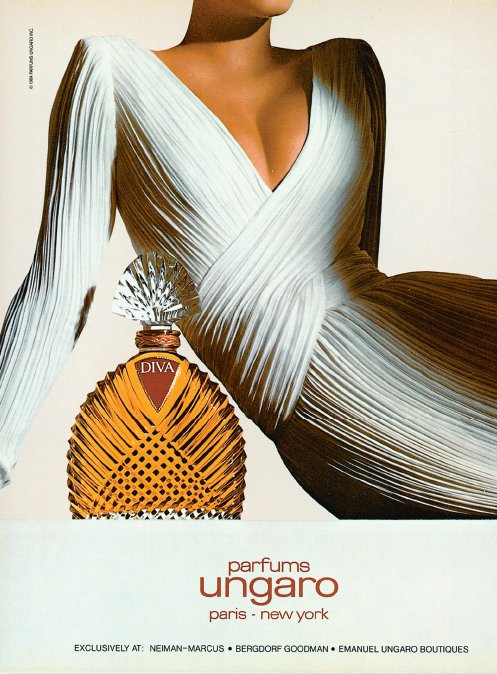

An iconic 1980s perfume, Diva, as its name announces, thinks big—big flashy bottle, big bold chypre, and, in this 1984 ad, a big bosom.

Paris, Poison, Paloma Picasso Mon Parfum (1980–1989)

I

t was the decade of

Dynasty, Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous,

and

Falcon Crest.

Yet for all its tacky excesses, the 1980s was also the last decade in perfumery of unselfconsciously grand perfumes. Chypres, mossy-fruity-animalics, and complex Oriental perfumes still gave perfumers’ imaginations—and its wearers’ noses—a workout. Perfumes got so strong and loud in the 1980s that New York restaurant owners were putting signs in their windows that said

PLEASE, NO WEARERS OF PASSION, GIORGIO, OR POISON

.

by Molyneux (1980)

Named after the intensely strong, powdery, and almost-perfumey brand of French cigarettes, Gauloises is a rosy, tobacco-y floral chypre with fresh-green top notes and a powdery base. Perhaps one of the last perfumes to pay homage to smoking culture, with a bottle that looks like an open pack of cigarettes and juice inside that—reminiscent of 1930s perfumes like Scandal—was probably made to harmonize with (cover up) the smell of cigarette smoke.

Top notes:

Bergamot, aldehyde, green note, coriander, hyacinth

Heart notes:

Jasmine, rose, orris, tuberose, lily of the valley

Base notes:

Musk, sandalwood, vetiver, oakmoss, amber, civet

by Pierre Balmain (1980)

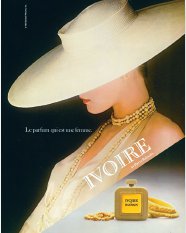

A 1981 ad for Pierre Balmain’s Ivoire

If you relied solely on random reviews of Ivoire on the Internet, you might believe that this early-1980s perfume merely screams “old lady” and “soapy” and call it a day. That would be a pity, because you’d miss out on a scent experience equivalent to going to a Sherwin-Williams paint shop and realizing, after an hour or so of comparing paint chips, that the shades in between stark white and cream can be staggering and infinitesimal.

Ivoire is an olfactory meditation on how a clean fragrance can have depth and texture, and how its individual notes can reverberate and resonate with one another to signify “clean” and “fresh” in a complex, even sensual, way. By evoking the tusk of an elephant or the keys of a piano, the name Ivoire asks us to think about the richness of white—its “off-whiteness” rather than its purity.

Upon first whiff, Ivoire gives us the whitest paint chip on the olfactory color wheel: fresh, bright, and citrusy top notes, further lifted by aldehydes. This first impression is a white of the blinding-flashbulb variety. This is only for a second, as the aldehydes die down and the piquancy of galbanum provides a wonderful first variation on clean—the resiny, piney, vegetal version, backed up by a hint of lemon and bergamot. Ivoire then moves subtly and almost seamlessly to its floral, spicy, and, yes, soapy heart.

Where Ivoire gets interesting for me is in the drydown. Its woody-incense finish is followed by ambery musk, like the burn you get when lighting incense is followed by its mellow diffusion. A whisper of the warmth from these notes moves you subtly from that white paint chip to the cream one. Or you could say they move your eye from the smoothness of the ivory tusk to a nick filled in with dirt that creates an interesting texture on the pristine surface. Like a Mark Rothko painting meditating on white, Ivoire’s notes hum and vibrate in unison.

Top notes:

Green accord, galbanum, bergamot, lemon, aldehydes

Heart notes:

Lily of the valley, rose, hyacinth, jasmine, carnation, orris, orchid, geranium

Base notes:

Cedar, musk, oakmoss, amber, raspberry, sandalwood

by Rochas (1980)

Perfumers:

Nicolas Mamounas and Roger Pellegrino

Macassar Ebony is a kind of wood with dinstinctive, contrasting streaks that was particularly popular with furniture makers during the Art Deco period. In an ad for Macassar perfume by Rochas, the image of a handsome man in a tux sits atop the pattern from Macassar Ebony wood, and his right cheek bears the mark of its unusual pattern.

Little known outside of the small circle of ex-lovers still mourning its loss, Macassar by Rochas is a stunning leather/woody chypre that balances aromatic herbs, fruit, spice, and florals with moss and leather. Its rich amber and spice notes could easily move it over into the Oriental category.

Bitter artemisia, fruit, and green notes launch Macassar, and it evolves into smooth, sweetish cedar warmed by a mossy animalic base. Hours into it, a camphory bitterness predominates, as its aromatic, mossy base reminds the fruit and florals who is boss.

Top notes:

Bergamot, artemisia, green note, pine needle, fruit note

Heart notes:

Jasmine, carnation, patchouli, vetiver, geranium, cedar

Base notes:

Leather, oakmoss, castoreum, amber, olibanum, musk

by Shiseido (1980)

Murasaki, which means “purple” in Japanese, is a green floral that starts off with a galbanum pucker of brightness soon softened by fresh florals and a subtle chypre base. (Rose and lily’s quiet duet can be heard most prominently.) Perfectly balanced and secure enough to not have to shout, Murasaki is poised somewhere between a 1970s green chypre and a 1990s clean scent. An hour into it, musk and amber turn Murasaki into a gorgeous, clean skin scent.

Top notes:

Galbanum, bergamot, gardenia, peach, hyacinth

Heart notes:

Orris, rose, lily of the valley, jasmine, lily

Base notes:

Sandalwood, oakmoss, vetiver, leather, musk, amber

by Chanel (1981)

Perfumer:

Jacques Polge

A soft cloud of cedar, coriander, and olibanum (with its cinnamon facets) hangs over the kingdom of Antaeus, named after the son of Gaia and Poseidon, Greek mythological deities of the earth and sea. Antaeus is a perfect balance of citrus, floral, spice, herbs,

leather, and amber, and projects a dreamy and gentle Eros rather than a raunchy one, in spite of a base with a roster of the usual (animalic) suspects. Unlike some men’s fragrances from the 1980s that haven’t aged well, Antaeus could be a new release from a niche house, and easily considered unisex. Gorgeous.

Top notes:

Bergamot, lemon, lime, fruit note, coriander, cedarleaf

Heart notes:

Orris, thyme, basil, rose, jasmine

Base notes:

Patchouli, leather, amber, olibanum, musk, castoreum, moss

by Giorgio of Beverly Hills (1981)

You know it. You may love it. But once you put it on, you won’t be able to get away from it, and those around you may hate you forever. That’s right—I’m talking about Giorgio. Giorgio of Beverly Hills.

In the late 1970s, Gale and Fred Hayman decided they needed an exclusive fragrance for their clothing boutique on Rodeo Drive. This exclusive fragrance, ironically (or, more likely, intentionally), ended up scenting every magazine, mall, big-haired salad eater, and Gucci bag–carrying Texas debutante in the 1980s like the “airborne toxic event” that threatens the characters in Don DeLillo’s surreal fantasia on consumerism and suburbia,

White Noise.

This

airborne toxic event starts off with a bright hit of green, followed by a massive synthetic-smelling accord of fruit notes plus orange blossom plus every cloyingly sweet facet that could be wrenched from Giorgio’s florals. There’s something kind of pleasant about the powdery and slightly rich drydown, but you can’t really experience it because the tuberose-gardenia-fruit monster stuns your nose into submission.

Giorgio doesn’t really develop so much as Enter the Building and stage a sit-in, demanding to be noticed: inert, bright, soapy, floral, and in-your-face sweet. It’s sunny and pretty in the way an immaculately made-up face Photoshopped within an inch of its life in a magazine is pretty, but there is no movement, multidimensionality, or life inside.

Giorgio is always described as a “big” scent, like many 1980s scent bombs, but it’s not Giorgio’s bigness or boldness that bothers me. I like the perverse Poison by Christian Dior, in small doses, and what some say is Giorgio’s reference scent, Robert Piguet’s Fracas, is as alive as a carnivorous plant. It’s Giorgio’s inorganic obtrusiveness that offends.

I may just be unable to objectively assess Giorgio’s aesthetic merits because there was a time growing up in Texas that I simply could not get away from it. It arrived with every fashion magazine that came in the mail in scent-strip form. (It was, in fact, the very first perfume that advertised itself not only through an image and a tagline, but also by actually smelling up the room.) You couldn’t go to the mall without being

inadvertently sprayed with it. And on top of everything, its celebration of “exclusivity” (it’s from Rodeo Drive!) was a bit ridiculous. (If you’ve ever watched soap operas, it’s as if Giorgio is being positioned as the “exotic” European dude who stirs up trouble for the townsfolk in Port Charles.)

Giorgio set the volume way up. Among other loud scents of the decade: Obsession, Poison, Amarige, and so many others. It actually makes sense that by the 1990s, our exhausted noses were proffered androgynous office scents that had wiped off all their fuchsia lipstick and purple eye shadow and retired their sequined evening gowns. Improbably, Giorgio is still available, but to me, it smells as dated as Robin Leach’s sign-off sounds: “Champagne wishes and caviar dreams!”

Top notes:

Green note, bergamot, fruit note, orange blossom, aldehyde

Heart notes:

Tuberose, gardenia, ylang-ylang, orchid

Base notes:

Sandalwood, cedarwood, musk, amber, moss, vanilla

by Krizia (1981)

Perfumer:

Maurice Roucel

Created for designer Mariuccia Mandelli for Krizia, a brand known for designs with bold shoulders, animal imagery, and intricate pleating, K by Krizia is a grand floral chypre that screams ’80s in the best possible way. Like Arpège or Crescendo, K is a creamy floral whose hint of velvety peach adds ripe fruitiness to this already lush perfume.

Top notes:

Aldehydes, peach, hyacinth, bergamot, neroli

Heart notes:

Jasmine, narcissus, tuberose, rose, lily of the valley, orris, orchid, carnation, orange blossom

Base notes:

Sandalwood, vetiver, musk, amber, moss, civet, vanilla, styrax, leather

by Yves Saint Laurent (1981)

Perfumer:

Pierre Bourdon

Anyone who has ever had her nose directly in the armpit of a man who is sweating and not wearing deodorant knows that the sharp, ammonia-like sting can either be pleasurable (say, you like the man) or unpleasurable (you don’t know this man from Adam and he’s raised his arm in front of your face on public transit).

Kouros’s extreme evocation of body odor arrives simultaneously with the scent of men’s cleaning products: fougère aftershave, the Pinaud powder that someone sprinkled on a man’s neck after a haircut, and, for those who despise Kouros, the oft-cited smell

of a urinal cake in the men’s bathroom of the club where he ended up. It’s an olfactory deconstruction of the ’80s man, from the moment he “smells,” to the shower he takes, to the aftershave he throws on, to his putting on a leather belt and shoes.

This olfactory slap in the face—bitter, sour, nose-clearingly spicy, and animalic—has to be smelled to be believed. It’s as if Bourdon took Robert Piguet’s Bandit’s training wheels off and decided to ride down the stink highway screaming, “Look, Ma—no hands!” The artemisia in Kouros is some of the bitterest, thorniest, and sharpest I’ve ever encountered in perfume, in spite of friendlier notes of honey, geranium, and bergamot.

Kouros belongs in that rarefied “love it or hate it” Difficult-Smelling Perfumes drawing room where Poison, Angel, and Bandit are smoking cigarettes, drinking scotch, and trading war stories. For those who love Kouros, its incense and woods are wrapped in the Eros implied by the name, which is the Greek word for the white statues of nubile young men that dot Greek islands. And for the others? The following sentiment from a commenter on a perfume forum says it all: “I would rather burn money than buy this fragrance.”

Top notes:

Aldehydes, artemisia, bergamot, coriander, clary sage

Heart notes:

Geranium, iris, jasmine, carnation, patchouli, vetiver, cinnamon

Base notes:

Oakmoss, honey, leather, musk, tonka, civet

(1981)

Perfumer:

Jean-Jacques Diener

In the same way that certain chic people are able to mix stripes with crazy prints, Must de Cartier combines fresh notes with a decadent gourmand base in a daring way that reads as beautiful for some people. For me, it bypassed rational analysis and went straight to my limbic system’s Decider, who nodded her head and said, “Yes, please. More.”

Must’s backstory, as recounted by Michael Edwards in

Perfume Legends,

is interesting. When Cartier was sending around perfume briefs to perfumers that described their ideal first fragrance, they had in mind two perfumes: a fresh perfume for daytime, and a more-seductive perfume for nighttime, probably in the Oriental family.

They were most interested in the young Givaudan perfumer Jean-Jacques Diener’s brief, so he decided, essentially, to put two fragrances together. Diener said he was inspired by Shalimar’s animalic-vanilla base, but wanted to change the top note from bergamot to galbanum, as he loved the way Aliage’s top notes were constructed. (Aliage is a green “sport scent,” remember!) He also gave it a civet overdose to make it even more animalic than Shalimar. Must’s “cool/warm accord,” according to Edwards, inspired Obsession, Roma by Laura Biagiotti, and Dune, among others.

The early Must eau de toilette was not constructed by Diener. It was supposed to be the “fresh” Cartier fragrance they had originally envisioned, which (rightly) confused the Must-lovers audience, who just expected a less-concentrated version. Cartier scrapped it in 1993 and replaced it with Must de Cartier II. (So if you want to try this odd perfume for yourself, either go to Sephora and spray it on, or get the vintage parfum. The vintage eau de toilette was not a favorite of mine.)

Must’s beguiling rush of galbanum and brightness at the beginning soon evolves into the lush floral, vanillic Oriental that is its true character. It goes from galbanum-pineapple to vanilla-amber-civet in a roller-coaster lurch that might make your stomach feel funny but Must’s intoxicating, animalic/gourmand drydown is 1980s excess at its unapologetic best.

Top notes:

Bergamot, aldehyde, lemon, rosewood, green notes, peach

Heart notes:

Jasmine, orris, carnation, orchid, ylang-ylang, leather, lily

Base notes:

Vanilla, amber, benzoin siam, opopanax, oakmoss, sandalwood, vetiver, musk, civet