Rome: An Empire's Story (27 page)

Cicero did not see things quite this way. In his orations—both in the courts and in the Senate—he repeatedly focused on the personal deficiencies (or merits) of the individuals involved. The interests of the Roman people would be best served if men like Verres were punished as they

deserved, and men like Pompey were given the power they needed to use their exceptional talent in the public interest. Cicero saw no necessary conflict between the interests of the Roman people and those of their subjects. One passage of his treatise

On Duties

claimed that before Sulla, Roman rule over her allies had been more like

patrocinium

(patronage or protection) than

imperium

(imperial rule):

8

there was no reason why that change could not be reversed. An open letter to his brother Quintus, ostensibly offering advice on his governorship of Asia, admitted the tensions that might arise between subjects and tax farmers, but recommended simply that all parties be urged to behave well.

9

The idea that some people were natural rulers and others naturally subjects was as old as Aristotle’s notorious justification of slavery. Besides, in

On Duties

, Cicero argued that the ethical course was always in fact the most expedient one. The problems of the Republican empire derived from moral deficiencies, not fundamental conflicts of interest or systemic failures. They demanded (no more than) a moral solution.

We might make two kinds of objection to this. First, there is a striking lack of analysis of structural problems. Was it not obvious that contracting out the collection of state revenues would lead to short-termism and abuse? Was it not clear that raising very large armies without any provision for their ultimate demobilization would cause problems? The answer to both questions must be yes, if only because these problems were not long after conceived and solved in exactly these terms. Under the Principate the duty of raising tribute was largely devolved to local authorities: they were perhaps no less rapacious, but did have a long-term interest in the stability of their own regions. From Augustus, soldiers were recruited for fixed terms, were discharged individually rather than by detachment, and a military treasury was established to fund their demobilization. It is impossible to know whether Cicero

could

not see these problems, or simply would not.

Second, Cicero’s concern for the subjects of empire falls a long way short of an imperial vocation for another reason. It seems clear that Romans of Cicero’s day had very little concept of empire in a modern sense.

10

One corollary was that subjects and foreigners were treated in much the same way. Both groups, for example, might send embassies, both might be subject to commands, neither had a recognized stake in the Roman state, or a claim to be consulted by it. Romans ruled well because they owed it to their nature to do so, not in respect of the rights of others. The term

imperium

was not used in a territorial sense until Augustus’ reign: until then it meant command and the power to do so.

Cicero is not our only witness to Republican imperialism, even if he is our best one. If we compare him to other writers of the period it is possible to see how conventional his views were. Sallust, writing history in the 40s, also saw the rise of Rome as accompanied by a collapse in morality, and attributed both war in the periphery and conflict in the centre to the moral deficiencies of Rome’s rulers.

11

Livy, writing a little later, seems to have told a similar story. Cicero perfectly expresses the ideological stance of the Roman elite, one that was determined not to see a clash between their own desires and the interests of the state, or between Roman interests and global justice. This did not mean they could not entertain the idea that Roman rule was brigandage on a large scale. Sallust fictionalized a wonderful letter sent by Mithridates to the Parthian emperor, condemning Roman imperialism.

Do you not know that the Romans have turned their arms in this direction only after Ocean put a limit to their western advance? From the beginning of time they have possessed nothing they have not stolen, their home, their wives, their lands, their empire. Once a group of wanderers without kin or homeland, their city has been founded as a plague for the entire world. No law, human or divine, can prevent them attacking allies and friends, neighbouring peoples and distant races alike, poor and rich without distinction. Everything that is not subject to their command they treat as enemies, and kings most of all.

12

The deft inversion of Rome’s own myths of origin—Romulus’ asylum, the Sabine women, and the Trojan settlement of Italy—and verbal allusions to Varro and others, reveal this as a pastiche aimed at Roman readers. It seems they enjoyed these travesties of empire, since Tacitus and imperial satirists also produced anti-Romes of this kind. Yet a belief in the essential justness of Roman rule was essential to maintain the divine mandate. What emerge from all these texts are the first signs of a universalizing ideology. The idea that Rome was patron of the entire world is one example, the comparisons with Alexander and the use of geographical imagery to sum up the empire are another.

13

For Cicero and his peers this universalism was not simply a matter of politics. It also formed part of an impulse to shape not just a Roman, but also a universalizing, view of classical culture.

Greek Intellectual Life in Rome

Cicero’s generation did not create either Latin literature or the idea of a distinctive Roman educational canon, but they fixed both in what would

become their classical forms. Like most peoples of the ancient Mediterranean, Romans had lived for centuries in a world where culture meant Greek culture. The first works written in Latin were intended for performance—the plays of Plautus, the hymn of Livius, the speeches of Cato.

14

From the beginning of the second century

BC

, a few historical and antiquarian works were produced in Latin: Cato led here as well. Yet many Roman authors continued to write in Greek, and philosophy and rhetoric, geography, medicine, and science were accessible only to Greek readers. We have little idea how many Romans were even interested in any of these subjects apart from philosophy before the middle of the second century

BC

. The creation of a comprehensive and self-sufficient Latin literary culture began in the 60s

BC

.

15

The issue was not access to Greek knowledge. There had been Greek cities in central Italy since the archaic age, and the influence of the imports, images, and ideas they brought was in some senses ubiquitous. The ancient cities of the Aegean were also easy to reach. Pictor travelled to Delphi and Cato must have had access to many Greek books when writing his account of Italian

Origins

. The first Latin epic poets were well aware not only of Homer, but also of the many later Greek critical and philosophical commentaries on his work. During Polybius’ long exile in Rome and his subsequent voluntary residence there, he had used the library of the kings of Macedon, brought back as plunder by Aemilius Paullus after the battle of Pydna. The fact that Paullus brought the library home suggests an interest in Greek scholarship as early as the early second century. Probably this interest was not new.

16

By the middle of the second century some Greeks seem to have realized the Roman elite was especially interested in philosophy. Athens sent an embassy to the Senate in 155 comprising the heads of the Stoic, Epicurean, and Peripatetic philosophical schools. Paullus’ son, Scipio Aemilianus, was the patron of not only Polybius but also of the Stoic Panaetius of Rhodes. Both scholars spent time with him in Rome, and accompanied him on his travels. But the total number of Greek scholars actually resident in Rome remained few until the Mithridatic Wars. Perhaps the same was true of the number of Romans who were genuinely interested in what they had to offer.

Things began to change in the late second century. One sign of a new interest in things Greek is a new interest in the Bay of Naples, where the cities of Cumae and Naples were the closest Greek cities to Rome.

17

Rome had created a cluster of colonies in Campania in the 190s. Anecdotes show some members of the Scipio family already had homes there in the early second century. Yet the first villas described as really spectacular date to the start of the last century

BC

: Marius’ Campanian retreat, built in the 90s

BC

, is one of the first certain examples. By the 60s and 50s the coastline was covered in those extraordinary pleasure complexes, images of which survive in Pompeian wall paintings and which have left flamboyant archaeological traces. The Emperor Augustus spent what were in effect vacations in the area, reserving for it Greek games, entertainments, and dress, in contrast to the rather sterner Roman traditionalism he displayed at home. Tiberius’ island retreat on Capri—perhaps because access was so difficult—attracted various stories of tyrannical cruelty and depravity. The Bay of Naples became imperial Rome’s Greek alter ego.

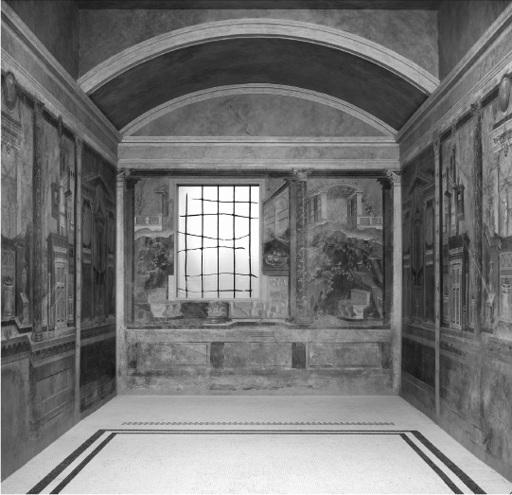

Fig 12.

One of the fresco wall paintings in the

cubiculum

(bedroom) from the Villa of P. Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale

Young aristocrats were now regularly sent to be educated in the ancient cities of the Aegean world. Athens was the key destination but there were also many visitors to Rhodes, which had become a major centre for education in rhetoric and philosophy. Both cities already drew young men from other Greek states. Now young Romans began to join them. Cicero and his brother were both in Athens in 79

BC

listening to the lectures of the great Academic philosopher Antiochus of Ascalon, a client of Lucullus. They were both in their mid-twenties. They then went on to visit Rhodes and Smyrna. Julius Caesar studied on Rhodes a few years later. Some of these visits seem timed to avoid difficult political situations at home, and some probably also served to remove wealthy young men from the temptations of the city. But they left a lasting impression. Cicero’s reminiscences of his youthful discovery of Greece evoke something of the Grand Tour of classical and Renaissance sites in Italy undertaken between the late seventeenth and the early nineteenth centuries by wealthy Europeans as a final stage in their cultural education.

Summers in Campania and educational trips to Greece cast Rome in a new light. Roman writers of Cicero’s age were acutely aware that when they entered a library almost all the books were in Greek. Most of the best libraries in Rome had once belonged to Hellenistic kings. Cicero and many others used the library set up by Lucullus in his retreat in the hill town of Tusculum.

18

Greek scholars as well as Roman ones made use of his collections. Mudslides from the eruption of Vesuvius in

AD

69 buried one elegant Herculaneum mansion, now known as the Villa of the Papyri after a great collection of philosophical works recovered there. The villa probably belonged to Calpurnius Piso, Caesar’s father-in-law, who was consul in 58 with Gabinius as a colleague. The long lines of its ornamental ponds flanked by bronzes, and its lavish marble architecture, were reproduced by J. Paul Getty in Malibu in the 1970s, and have now been recreated again with loving digital reconstruction.

19

Its library of philosophical works was a relic of the long residence there of the Greek polymath Philodemus of Gadara, who wrote on aesthetics and literary criticism as well as Epicureanism.

20

Vitruvius’ manual

On Architecture

confirms what the Vesuvian villas suggest, that the Roman rich deliberately incorporated in their residences spaces designed to evoke Greek culture and these were often designated by Greek names: the

oecus

was a Greek dining room, the

peristylum

a Greek garden, the

bibliotheke

the regular term for library. Many of these rooms and terms did not correspond very closely to what archaeology shows actually

existed in contemporary eastern Mediterranean cities such as Athens and Ephesus. Romans were not trying to recreate a contemporary Greek world in Italy. Cicero’s retreat in Tusculum included two areas he called

gymnasia

, adapting the terms from a characteristic Greek institution dedicated to exercise and the education of elite males. One he named the

Lyceum

after Aristotle’s school, the other the

Academy

after Plato’s. A series of letters survives in which he asks his friend Atticus to try and obtain suitable Greek statuary to decorate these spaces.

21

No doubt his villa near Puteoli had many Greek spaces too. But there was also the sternly Roman

domus

on the Palatine, and probably the Tusculan villa had more Roman spaces for other aspects of his life. He and his peers were not trying to become Greek so much as to incorporate a carefully selected portion of Greek culture into their own lives.

22