Rome: An Empire's Story (24 page)

Most impressive of all was Pompey. After the long campaigns in Spain against Sertorius, Pompey returned to Italy just in time to join Marcus Crassus in the war against Spartacus, and to steal some of his thunder. By 70

BC

, Pompey and Crassus were consuls together, in an uneasy alliance. This was the year Cicero drove Verres into exile, with a little help from Pompey, in fact. But it was a great command against the pirates, obtained with the help of Gabinius, that enabled Pompey to finally pull ahead of his competitors. His rapid success led to another bill, supported by Cicero among others, by which the war against Mithridates was transferred from Lucullus to Pompey. Pompey rapidly repelled Mithridates, who fled to the Crimea and committed suicide, dismantled his kingdom, and pursued his allies. He then remained in the east, in effect conducting a global reorganization of Roman territories and alliances along the Parthian frontier.

During Pompey’s absence Rome was gripped once more by civil conflict. Cicero was consul in 63 and had to deal with a conspiracy that drew on a poisonous cocktail of social discontent and frustrated aristocratic ambition. Its leader, Catiline, enjoyed some real support and sympathy, including that of both Crassus and Caesar who shared his

popularis

politics. Cicero was given a free hand to arrest and execute the conspirators largely because the majority of senators, remembering Sulla’s terrifying return from the east in 84, feared the kind of solution Pompey that might impose if it were left up to him. The same year Caesar managed to bribe his way to election as the most senior priest, the

pontifex maximus

.

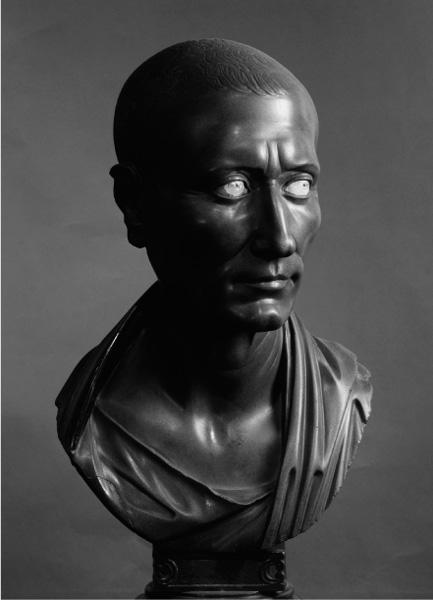

Fig 10.

Bust of Julius Caesar

Pompey finally returned in 62

BC

and surprised many by stepping down from his command and dismissing his troops. But when the Senate would not ratify his eastern settlements or help find land for his soldiers, he formed a new alliance with Crassus and Julius Caesar. Historians today know this as

the First Triumvirate, but it had no formal legal standing. Backed by the threat of Pompey’s veterans, combined with Pompey and Crassus’ financial muscle, and the influence that Crassus and Caesar had over the people, the three effectively ran Rome for nearly a decade, picking the magistrates, allocating provinces and armies (mostly to themselves), and making debate in the Senate or the assemblies pointless. Their control was precarious and frequently challenged, and their opponents repeatedly tried to pull them apart. At times they sponsored different gangs in the city. For much of the 50s, Rome was a scene of mob warfare and appalling violence. Yet mutual interest kept them together.

What they themselves wanted most were super-commands of the kind Pompey had already enjoyed. After holding the consulship in 59 Caesar took the province of Cisalpine Gaul, the area that stretched across the Po Valley and up to the Alps. He was assigned a grand army and team of senatorial deputies, termed legates. The province of Transalpine Gaul was soon added to the command. It seems Caesar had first expected to be marching north-east into the Balkans following rumours of war, but news that the Helvetii were planning to leave their Alpine territory and pass through southern Gaul diverted him west of the Alps. That war began eight years of campaigns that resulted in the conquest of Gaul and invasions of Britain and Germany. The first books of his

Commentaries

go to great lengths to explain why each campaign was justified. It is difficult to believe Roman interests were really threatened, even by the Helvetian migration, but memories of the Cimbri and Teutones were recent, and he was careful to make the connection. An element of mission creep is clear. Caesar’s later books spent less time justifying particular conflicts, and instead emphasized the unprecedented extensions of the power of the Roman people he had brought about.

3

Roman armies had crossed both the Ocean and the Rhine for the first time, and city after city had fallen to his armies. News of his victories was greeted with public rejoicing in Rome. The campaigns were certainly lucrative, allowing Caesar to pay off the debts accumulated in successive election campaigns, and to begin several monumental building projects in Rome. The same years saw the complete disappearance of the gold and silver coinages of Gaul.

Caesar’s successes only inflamed the ambitions of his allies. By agreement among the three of them, Pompey and Crassus took the consulship for 55

BC

. Both then claimed their own great provinces. Pompey was given Spain with the unprecedented permission to govern

in absentia

through legates of

his own choosing. Crassus was assigned the province of Syria and a command against the Parthian Empire, with an army to match. The Roman and Parthian empires shared a small border and a much greater zone over which each tried to exercise influence. There is no sign that the Parthians wanted war with Rome; indeed they had declined to support Mithridates. All the same they looked a tempting target, and in late 55

BC

Crassus headed east with an army based on seven legions. He spent the next year in Syria building up his forces. But not long after crossing the Euphrates in 53

BC

, Crassus was defeated at Carrhae. His army was slaughtered and their standards were captured. Crassus himself was soon tracked down and killed. Avenging Crassus was allegedly one of Caesar’s future plans when he was assassinated. Two decades later Mark Antony did mount an invasion, one that was unsuccessful, if not as disastrous as that of Crassus. Parthia took advantage of Roman civil wars to raid the east, but seemed content enough to cease hostilities when Augustus offered peace. Every indication shows that Crassus’ campaign was as unnecessary as it was disastrous.

Up until the death of Crassus, the three-headed beast that ruled Rome seemed to be going from strength to strength. Together Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus commanded huge armies. Cicero and his friends were outraged, but the generals’ exploits made them popular with the people. Only those senators who did not enjoy their patronage were left out of the loop, and it was easy to see the sour grapes behind the high-minded talk of senatorial libery.

The Governance of the Empire

Rivalry between individuals was traditional in Roman politics. Roman writers even idealized it, seeing a competition to outdo each other in virtue as one of the driving forces of Roman success. A fragment of a speech of Gracchus warns the people of Rome that all those who address them are motivated by self-interest but his own self-interest is in providing them with the best possible advice. That was a rhetorical flourish but it reflected an ideology as well. Yet the negative side of competition was all too evident. Civil war was bad enough. But there was also an incoherence built into any system that worked by delegating the power to make major decisions to individuals without imposing on them any discipline beyond the fear of the law courts on their return. During the 50s even that sanction had disappeared. But perhaps one reason the activities of Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus

did not arouse more opposition outside the senatorial elite was that the system they had overthrown was clearly badly broken already.

In

Chapter 7

I told the story of how, in the generation following Rome’s final defeat of Macedon, the Mediterranean world was gripped by successive crises. I explained those crises as a result of the inconsistent treatment given former allies such as Jugurtha and Mithridates, combined with an erratic alternation of long periods of neglect of the provinces and terrifying interventions like the sack of Corinth. Where tax collection had been handed over to public contractors with no interest in justice or the long-term viability of imperial government, all the conditions were ready for rebellion. These problems were structural. The Senate’s ‘policy’ was little more than the sum of the individual opinions of its members. There are signs that some

popularis

politicians thought that the behaviour of governors and generals could be controlled through subjecting them to more independent courts and more detailed legislation. One of Gaius Gracchus’ most unpopular acts had been to give control of the corruption courts to the equestrians. His enemies were outraged. Why should they be subject to trial by their social inferiors? And anyway, it meant more people who would have to be paid off. Similar ideas lay behind the great law on the provinces that required Roman pro-magistrates to work together, and alongside allies including the kings of Cyrene, Cyprus, and Egypt. But the failure of

popularis

politics after Sulla—and the absence of institutions able to enforce such laws—meant that that provincial government in the last century

BC

was no better than it had been in the second.

The enemy of consistency was ambition. Many senators never won more than a single magistracy in their lives. For the rest a provincial command would come once, or maybe twice in a lifetime. With competition at home becoming more intense and more expensive, many governors clearly felt they had to make their year of service pay. The infamous Verres, whose prosecution in 70

BC

established Cicero’s reputation, allegedly quipped that a governor needed to raise three fortunes in his provinces, the first to pay back the debts he had incurred in getting elected, the second for himself, and the third to bribe the jurors on his return. Then there were the many other groups with vested interests in the provinces, Roman landowners and traders, those who lent money to provincials, and most of all those with public contracts, like the tax farmers. These were well connected, and an ambitious politician dared not offend, in his one year in office, a constituency who could help or hinder him for the rest of his career. Even Cicero,

who tried very hard to govern justly during his single period as a governor in Cilicia in 51–50, found it hard to resist demands from back home. One man wanted help recovering sums he had lent provincials at ruinous rates, another wanted Cicero to find some panthers he could display in Rome, and even Cicero wondered if the risk of suppressing some banditry would be worth it if he could return to celebrate an

ovatio

, a sort of lesser triumph. Others had fewer scruples. Pro-magistrates exercised the power of life and death in their provinces, gave justice to cities and kings, and when far enough away from Rome they could behave like little autocrats. Many did. Verres allegedly crucified his enemies in sight of Italy. Another governor, when drunk, ordered an enemy envoy to be executed on the spot, to please his lover who complained that by accompanying him on campaign he was missing the games in Rome. Not all governors were wicked, but none wished to be regulated.

To the other structural deficiencies of the Republican hegemony, then, we can add an inability to operate effectively on any scale larger than could be handled by one man with a moderate-sized army and an oversized ego; and a system of government that more or less promoted corruption. Extortion, whether by governors themselves or conducted by tax farmers and other

publicani

with the governor turning a blind eye, increased the support that provincials gave figures like Mithridates. The reluctance of governors to work together made it difficult to tackle very large-scale problems. There had always been stories of failures of cooperation between consuls, both at home and on the battlefield. But as the empire grew, the problems became more acute.

Piracy is a case in point.

4

The enemy was highly mobile, not confined to one particular sphere of command, and indeed could move rapidly between them. Pro-magistrates commanding in Macedonia and Asia, the free cities of the Aegean, and the kings of western Asia could not work together effectively. The first Roman attempt to deal with piracy was probably the campaign waged by Marcus Antonius (Mark Antony’s grandfather) in 102

BC

. It seems a Roman fleet was moved into the Aegean, based first in the allied city of Athens, then campaigned off the southern coast of Asia Minor, supported by other allies including two Greek cities with small fleets, Rhodes and Byzantium. After victories in Cilicia, Antonius was awarded a triumph. But whatever solution he achieved was merely temporary. The

popularis

law on provincial government was passed just a year or two later, and piracy clearly remained a major priority. A new pro-magistrate is now mentioned

in Cilicia, notorious as the ‘bad lands’ of Asia Minor. Yet the problem persisted. Some pirate bands cooperated with Mithridates against Rome in the 80s. Pirates were able to kidnap a young Julius Caesar in the mid-70s. Kidnapping for ransom was a nuisance but the real risk came from the pirates’ capacity to interrupt the supply of grain to the city of Rome. The conquest of Crete in 69 was largely motivated by the desire to shut down other pirate bases. Yet pirates were mobile and had many bases. Food shortages and rising prices in Rome pushed piracy to the top of the political agenda. With hindsight we can see the problem was systemic, the product of the absence of any permanent security system in the region. The great Greek kingdoms could no longer maintain fleets, and naval powers like Rhodes had been humiliated. No permanent fleets or naval patrols were created until the reign of Augustus.