Rogue Heroes: The History of the SAS, Britain's Secret Special Forces Unit That Sabotaged the Nazis and Changed the Nature of War (36 page)

Authors: Ben Macintyre

Tags: #World War II, #History, #True Crime, #Espionage, #Europe, #Military, #Great Britain

The fate of another group of 2SAS men was very different. Sergeant Bill Foster and Corporal James Shortall landed safely and set out to attack a section of railway between Genoa and La Spezia. They never reached it. On September 25, they were captured by German troops and taken to the nearest infantry headquarters and interrogated. Both refused to reveal the name of their unit or the purpose of their mission. They were then locked in the local Italian police station. Three days later, the German military police brought the two prisoners back to headquarters, where a firing squad of ten was assembled “to shoot two men…Englishmen who had landed by parachute.” The prisoners were driven to a disused pottery factory and marched to a rise above an old loading track, where stood a lone tree. A statement was read out proclaiming that the two men had been condemned to death for sabotage, “by order of the Führer.”

Foster was tied to the tree. He refused to be blindfolded, but asked for a priest. “We have no time for that,” he was told. With Shortall standing just a few feet away, the execution squad aimed and fired. One of the German witnesses recalled Shortall’s “impassive attitude” as Foster’s body was dragged away. Shortall was shot without his uttering another word. As he lay on the ground, a German officer administered a final bullet to the head with his revolver. The men were buried in an unmarked grave in the factory grounds. Two days later, two more men from 2SAS were executed, just twenty-four hours after being captured.

Hitler’s revenge on the SAS had begun in earnest.

On June 1, 1944, five days before D-Day, John Tonkin was summoned to a briefing at General Dwight Eisenhower’s headquarters in London. Eight months earlier the SAS officer had escaped from German captivity after his bizarrely civilized chicken dinner with a senior German general. Now promoted to captain, Tonkin was told that he and his squadron from 1SAS would be parachuting into the west of France on D-Day on an operation code-named Bulbasket. Once the invasion was under way, German troops stationed in the south would undoubtedly begin heading north toward Normandy to repel the Allied invaders. Tonkin’s task was to delay those reinforcements in any way he could.

The previous six months, leading up to the great invasion of Europe, had seen many changes to the SAS: the regiment had regained a name, lost its distinctive beret and a commanding officer, and attracted a huge influx of new recruits. The Special Raiding Squadron reverted to its original name, 1SAS. Along with 2SAS, two French SAS regiments, a Belgian contingent, and a signals squadron, the total strength of the new SAS Brigade swelled to a mighty 2,500 men. The brigade came under the command of a regular gunner, Brigadier Roderick McLeod, considered by some to be “out of his depth with SAS officers and men.”

The Special Boat Squadron, under Jellicoe, had meanwhile achieved mixed success harassing Axis forces on the islands of the Mediterranean. The first SBS operation on German-held Crete in June 1943 had landed a force of thirty soldiers by submarine, which then marched sixty miles over rugged terrain and successfully destroyed fuel dumps and aircraft. But another SBS operation on Sardinia a week later ended in disaster when the raiders were betrayed to the Italians by their interpreter.

There were many familiar faces in the ranks of 1SAS: Bill Fraser, recovered from his wound at Termoli, commanded a squadron; Seekings was reunited with Cooper, now a newly minted lieutenant; Mike Sadler, the skilled desert navigator, rejoined 1SAS as an intelligence officer, but not before touring the United States as a military poster boy to raise money for war bonds. 1SAS also recruited its first military chaplain, the Rev. Fraser McLuskey.

As part of the 21st Army Group—the British formation assigned to Operation Overlord, the Allied invasion of Europe in the west—SAS soldiers were required from 1944 onward to wear the conventional red beret of airborne troops. Paddy Mayne ignored this constraint and continued to sport the beige one.

1SAS had returned to Britain early in the new year of 1944. Each of the men was given a month’s leave, a travel voucher, and £100. Some rushed off to see wives and sweethearts. Some returned to their families. Some rushed to the nearest pub. Paddy Mayne disappeared. Again, no one was quite sure where he had gone. By February, the men were encamped in two disused lace mills at Darvel, a village in East Ayrshire, undergoing a new round of grueling training in the damp surrounding hills. The mood was convivial, agitated, and anticipatory. The invasion of Fortress Europe was at hand, and everyone knew it. Mayne led a new recruitment drive. The Ulsterman exhibited no nerves whatever during military action, but addressing an audience reduced him to squeaky-voiced terror. Even so, his descriptions of SAS life prompted dozens of volunteers. At least 130 new men were drawn from the British Resistance Organization’s Auxiliaries, a unit originally intended to resist the Nazi invasion of Britain that never materialized. Now they would be helping to invade Nazi-occupied Europe. While the troops continued training in Ayrshire—in explosives, parachuting, firearms, and unarmed combat—back in London the battle over how best to deploy the SAS erupted once more, and claimed a prominent casualty. When Bill Stirling discovered that the high command intended to drop SAS units thirty-six hours ahead of the main invasion, to act as a barrier of shock troops between the fighting front and the German reserves, he hit the roof: the SAS would be placed in maximum danger for minimal strategic advantage. Most SAS officers agreed, believing that the regiment should operate deep behind the front lines, not on them.

Bill Stirling penned a blistering letter to Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), explaining exactly how stupid this idea was (among the traits shared by the Stirling brothers was a talent for extreme epistolary rudeness). Refusing to retract his criticisms, he resigned, to be replaced as commander of 2SAS by his deputy, Major Brian Franks. David Stirling believed that his brother had saved the SAS: “He lost his battle, but the regiment won theirs.” It had been a brave act, supported by many of the men, but it signaled the end of the Stirling brothers’ leadership of the SAS.

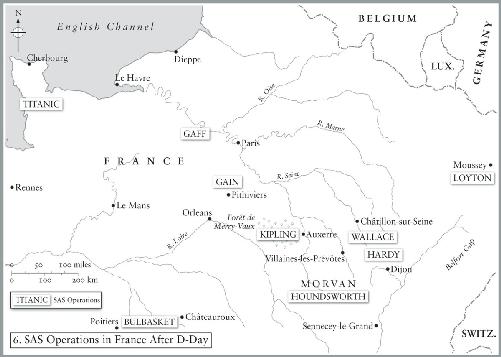

Like many dramatic gestures, Bill Stirling’s resignation proved premature, since his concerns were eventually given due consideration: the plan for deployment of the SAS was amended to something far closer to the role envisaged by the Stirling brothers. Only five three-man teams would be dropped immediately beyond the Normandy beaches on the eve of D-Day, to sow confusion by imitating a much larger paratroop force—an operation code-named Titanic. A large French force would be deployed in Brittany, again to confuse the Germans about Allied intentions. But the bulk of the SAS fighting units would be dropped far behind the lines after D-Day, to destroy communications, impede the movement of reinforcements, train up local resistance fighters, spot targets for Allied bombers, and generally foment havoc.

Two squadrons of 1SAS would be sent deep into France on D-Day itself: one, under Bill Fraser, would parachute in near Dijon; the other, commanded by John Tonkin, would land farther west, near Poitiers. The two missions were code-named Houndsworth and Bulbasket, ideally meaningless names, although the latter may have derived from Tonkin’s nickname “Bullshit Basket,” bestowed on account of his penchant for amusing tall stories. Operation Overlord, the invasion of France, depended on establishing a secure foothold in Normandy, swiftly and with as little warning as possible. If the Germans were able to deploy reinforcements with sufficient speed and efficiency, the invaders might, as Hitler demanded, be hurled “back into the sea.” Both Houndsworth and Bulbasket would aim to sabotage rail links, ambush convoys, and above all slow down the northward progress of the formidable 2nd SS Panzer Division—known as Das Reich, a brutally battle-hardened unit comprising twenty thousand men and ninety-nine heavy and sixty-four lighter tanks—as it rumbled toward the Normandy beachheads.

The days leading up to the jump were spent attending tutorials given by the Special Operations Executive (SOE), the secret unit formed by Churchill to “set Europe ablaze” by conducting sabotage, espionage, and resistance in countries under Nazi occupation. Tonkin and Fraser would be liaising on the ground with SOE agents, and the complex constellation of local partisan groups, collectively known as the “maquis” (derived from the dense shrubland of the Mediterranean, which was considered ideal for guerrilla fighting). One veteran agent warned Tonkin not to put too much faith in the French resistance, and to remember “the mutual ambition and jealousy that dog them.” Tonkin spent the evening before D-Day doing jigsaw puzzles with Violette Szabo, the SOE agent whose subsequent actions would mark a high point of wartime heroism. The young agent knew what the stakes were: Hitler’s infamous Commando Order, requiring the summary execution of any soldier found behind the lines whether in or out of uniform, meant that the “winning” part of the SAS motto now required an even greater degree of “daring.” One French briefing officer was particularly blunt about the consequences: “Most German commanders would obey this order. And as to the SS, it didn’t matter as they would have shot you even before Hitler’s order…Don’t get captured and if you’re cornered, go down fighting.”

Accompanied by Lieutenant Richard Crisp, Tonkin jumped out of a Halifax bomber shortly after 1:00 a.m. on June 6, 1944, floated gently down through bright moonlight, and made a perfect landing in the Brenne Marshes, between Poitiers and Châteauroux. “I doubt if I’d have broken an egg if I’d landed on it,” wrote Tonkin, having lost much of his kit but none of his sense of humor. He attached a message to the foot of the homing pigeon he had carried to France in a rucksack—still one of the most reliable forms of communication in war—and then launched the bird “with more force than skill, for it circled twice and made straight for the nearest big tree, fifty yards away. I believe it may still be there.”

Tonkin’s task was to hide out in the woods, gather his force of around forty men, make contact with the SOE spy network and the local maquis, and then set about impeding the passage of German troops moving north, by any and every means possible—a mission far more challenging than it sounds. Some in SOE considered the SAS troops a liability, conspicuous in their uniforms and apt to “draw danger not only on themselves but on all the maquis in the region.” Tonkin’s force was not small enough to be easily concealed from local eyes, but not big enough to mount any serious and long-term impediment to the German advance. Roadblocks and small arms would not stop the mighty Das Reich tanks. “It was ridiculous to think that scattered parties of parachutists could do anything much to delay the arrival of panzer divisions,” said one gloomy officer. Ridiculously difficult, perhaps—but not impossible.

Soon after dawn, a young maquisard arrived at the drop zone, carrying a Sten gun, the submachine gun much favored by resistance groups. A stilted exchange of passwords took place.

“Is there a house in the woods?” asked Tonkin, in wobbly French.

“Yes, but it is not very good,” said Agent “Samuel,” whose fantastical real name was Major René Amédée Louis Pierre Maingard de la Ville-ès-Offrans, an aristocratic twenty-five-year-old Mauritian and one of the pillars of SOE’s French section.

Over the ensuing days, as Tonkin waited for the rest of his force to be dropped into the Vienne, in west-central France, the young French spy painstakingly explained the state of the local resistance. The region contained more than seven thousand maquis. These were enthusiastic and brave, but most were woefully underequipped and largely untrained. The situation was further complicated by the bitter antipathy between the communist and the Gaullist groups, who had violently clashing political agendas. The Vienne also contained its share of Nazi collaborators. Tonkin decided to put his trust in the maquis and rely on them to provide protection and support, and to keep a lookout for German forces: a risky strategy, but the only one available. Tonkin sent back an “enthusiastic message re relations with populace.”

Having first set up camp in a wood near Pouillac, Tonkin’s squadron settled down to await the airdrop of supplies, including four jeeps—to be mounted with Vickers guns in the approved desert manner.