Rogue Heroes: The History of the SAS, Britain's Secret Special Forces Unit That Sabotaged the Nazis and Changed the Nature of War (33 page)

Authors: Ben Macintyre

Tags: #World War II, #History, #True Crime, #Espionage, #Europe, #Military, #Great Britain

Teddy Schurch had been flown to Rome shortly before Stirling’s capture. When his new commanding officer, one Captain Morocco, told him that “a very important person had been captured,” none other than the leader of the SAS, Schurch seems to have felt a surge of something like professional pride: “At last he was going to meet the commanding officer of the men and officers with whom he had spent all his time obtaining information.” Morocco ordered Schurch to “obtain all possible information about Stirling and his organization,” and in particular the name of the officer who would succeed him as leader of the SAS.

Quite how much Stirling inadvertently divulged to the stool pigeon over the next two weeks has never been revealed. In a witness statement made at Schurch’s treason trial, Stirling claimed he had been warned by another officer that Captain Richards was working for the Italians, and that he had been on his guard from the start: “Such information as I passed was untrue and designed to deceive him…I cannot remember discussing the name of my successor in the SAS. In fact at that time I was unaware of my successor’s identity.” Schurch remembered their conversations differently. “As all the necessary information regarding the SAS had already been obtained, I was told only to obtain the name of Colonel Stirling’s successor. This I found out to be a Captain Paddy Mayne.” There was really only one person capable of taking over the regiment, and Stirling appears to have revealed as much to Schurch. This information was undoubtedly shared with Nazi intelligence. Bizarrely, the Germans knew he would be taking over the SAS before Mayne knew himself.

—

The desert war was drawing to an end, and with victory in sight in North Africa the role, the location, and the very nature of the SAS would change once again. It had already been altered beyond all recognition from the handful of soldiers dropped into the desert in Operation Squatter. Many of the “Originals,” as the first recruits described themselves, were gone. David Stirling was eventually transferred to Colditz, the notorious German POW camp, where he would be reunited with Georges Bergé and Augustin Jordan, the French SAS commanders captured earlier. Jim Almonds remained a prisoner. Fitzroy Maclean had been dispatched by Churchill to Yugoslavia, to link up with Tito’s partisans. Jock Lewes was dead, along with Germain Guerpillon, André Zirnheld, and many others. American-born Pat Riley, the Irishman Chris O’Dowd, Bill Fraser, Reg Seekings, and Johnny Cooper had all survived, and would play key roles in the second great chapter of the SAS story. Mike Sadler, having finally persuaded the Americans that he was not a spy, helped to guide the advancing Eighth Army across the desert for the final act of the war in North Africa, and then rejoined the SAS. The force, now composed of two regiments, would plunge into the war in Europe under the leadership of a fiery, inspiring, occasionally violent Northern Irishman. The SAS under Paddy Mayne would be a very different force.

Malcolm Pleydell took a new posting in 64 General Hospital in Cairo. The young doctor left the SAS with a hymn of love to the desert.

This was the end of our campaigning in Africa, and now we might bid farewell to the desert: the loneliness, the solace and the clean sterility. Here in these little cliffs and caves that had been our hiding places, we had left our mark. In a few weeks they would be erased by wind and sand. Here we had learned to navigate, to plot our course and mark our position; here we had grown wise, becoming self-reliant and tolerant of the humours of others; we had matured, we had known greater mental sufficiency, had discovered our fears and our reactions to danger, and had tried to overcome them. We had become familiar with hardship and with the submission of the body to rigid control. This was the bequest of the desert. Our time had not been wasted.

“The ship is without a rudder,” Malcolm Pleydell observed sadly as he took his leave of the SAS, two months after the capture of David Stirling. “There is no one with his flair.” Paddy Mayne was a fighting commander, beloved and respected for it, but bravery is only one aspect of leadership. However much he might be admired for his battlefield panache, he was unexploded ordnance, and his subordinates trod warily around him. He was baffled and bored by paperwork. He lacked Stirling’s polish and willingness to charm the top brass, many of whom felt that the SAS had “outlived its usefulness.” He was also in trouble, again. In March, Mayne learned that his father had died. He requested three days’ leave to return to Northern Ireland for the funeral; this was refused without explanation. Mayne smoldered with resentment, drank, and then went, as Seekings put it, “on the rampage.” In the course of a few hours in Cairo, it was said, he smashed up several restaurants, got into a punch-up with half a dozen military policemen, and was flung into a cell.

There was widespread expectation in the ranks that, with Mayne out of control and Stirling in a POW camp, the regiment would soon be disbanded. But Mayne somehow managed to get himself released and argued fiercely that the regiment should be preserved; eventually a compromise was reached, involving considerable restructuring. The original unit, 1SAS, would be split into two parts: the Special Boat Squadron (SBS), under George Jellicoe, to carry out amphibious operations, and the Special Raiding Squadron (SRS), under Mayne, to be used as assault troops in the coming invasion of Europe.

Jellicoe’s SBS, 250-strong, moved to Haifa and began training for operations in the Aegean. The 2SAS, meanwhile, the new sister regiment formed under David Stirling’s brother Bill, would continue training in northern Algeria before deployment in the Mediterranean and then in occupied Europe.

The story of the two SAS regiments would now evolve in parallel, sometimes in combination, and frequently in competition.

Mayne’s newly named section, the SRS, though it included many SAS veterans, was a far cry from the muscular, mobile force Stirling had dreamed of before his capture: reduced in strength to between 300 and 350 men, it was now under the overall command of HQ Raiding Forces, to be used in straightforward attacking operations. The SRS was no longer the independent, agile, self-sustaining SAS of the desert, but the pointed tip of a much larger army, a tactical force. In all but spirit, the 1SAS had ceased to exist. It would soon return to its original shape and purpose, but for the moment, in order to survive, the SAS had to fall into line. Uncharacteristically, Mayne acquiesced in this uncomfortable new arrangement without resigning, getting excessively drunk, or hitting anyone.

—

In the late spring of 1943, the SRS began a fresh round of intensive training in Azzib, Palestine: endurance marches around Lake Tiberias in broiling heat, cliff scaling, weapons use, bayonet practice, wire cutting, beach landings, and the use of explosives. A new mortar section came into being under Alex Muirhead, a young officer who knew little about mortars but possessed the sort of mathematical mind necessary for the precise and devastating art of dropping shells onto enemy positions. “Soon he could put 12 rounds into the air before the first one had hit the ground,” a contemporary noted admiringly.

For some of the veterans there was a sense of transition. Bill Fraser, now deprived of the company of his dog, Withers, seemed increasingly distant and elusive. Johnny Cooper had volunteered for officer training, leaving Reg Seekings without a restraining voice, and more prone to pick fights than ever. The Irishman Chris O’Dowd kept up a steady stream of jokes, but there was tension within the SRS: the old guard rubbed shoulders with a fresh batch of newcomers, not always comfortably. Men like Seekings considered themselves a battle-hardened, desert-baked elite and did not try to disguise it. No one had a clue what Mayne’s training program was leading up to (including Mayne himself), save that it must involve heat, cliffs, hand-to-hand fighting, and lobbing mortar shells.

On June 28, the SRS headed for the port of Suez, and climbed aboard the

Ulster Monarch,

a bulky former passenger ferry that had once operated in the Irish Sea, to be delivered to its first mission in Italy. Before the ship set sail, General Montgomery arrived for an inspection and made his standard exhortatory speech. As with all relations between the general and the SAS, the event assumed an awkward aspect. Monty had expected his address to be met with loud adulatory applause, the sound he liked most, but for some reason it had been decided to hold back on cheering until he returned to shore. His words were greeted with total silence. Monty may have wondered if the truculent spirit of David Stirling was somehow aboard the ship. Even so, he was impressed by the sight of the fit troops, lined up in their beige berets. “Very smart,” he muttered as he descended the gangplank and the cheers finally erupted. “I like their hats.”

As the

Ulster Monarch

steamed out of Suez and headed north, the shape of what lay ahead began to emerge, not least in the form of the secret password with which the troops would identify one another on the forthcoming operation: the phrase “Desert Rats” would be met with the response “Kill the Italians.”

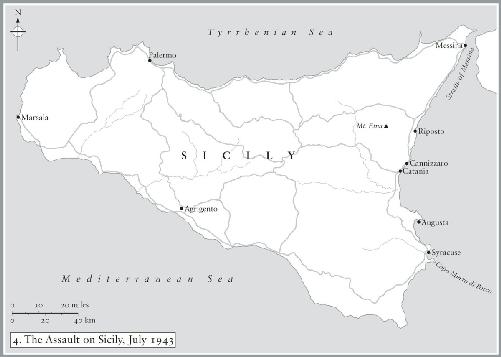

The largest amphibious assault force ever assembled was already gathering for the invasion of Sicily: more than three thousand ships carrying 160,000 soldiers, the combined forces of Montgomery’s Eighth Army and the US Seventh Army under General George Patton. D-Day in Sicily was set for the early hours of July 10, 1943. The task of the SRS was to knock out the artillery defenses at a key point on the Sicilian coast: Capo Murro di Porco—Cape of the Pig’s Snout—a distinctly nasal promontory stretching into the sea south of Syracuse on the island’s eastern side. The cape was a “veritable fortress,” according to intelligence reports, perched atop a steep rock cliff and equipped with searchlights, a range of heavy guns, and Italian defenders who would outnumber the assault team “by 50 to one.” If the SRS failed to knock out the Italian guns, the invasion fleet aiming for this section of the coast could be blasted to shreds long before they reached the shore.

At 1:00 on the morning of the invasion, 287 men of the Special Raiding Squadron, led by Mayne and including Seekings, Fraser, and many other desert veterans, climbed into landing craft and were lowered from the

Ulster Monarch

into a bucking sea. The wind had risen to the point where any kind of seaborne operation seemed barely possible, let alone a full-scale invasion. As the landing craft plowed through the rising chop, many of the men were sick into cardboard buckets, which promptly fell apart. No one spoke. Less than a mile from shore, the wind abruptly dropped and voices could be heard drifting across the waves. Shapes bobbed on the surface through the gloom, accompanied by urgent cries for help, in English. Up ahead, dozens of Allied paratroopers were drowning. Dispatched in gliders to land in the Sicilian interior and wreak mayhem ahead of the main force, many had been blown off course by the high wind and crash-landed in the sea. One group perched on a downed glider was picked up by an SAS launch, but most were left behind. The landing craft plowed ahead. “The poor devils were shouting for help but we didn’t stop,” remembered Reg Seekings. For some of the SAS men, the decision to press on brought back memories of the moment, so many months earlier, when the men injured during Operation Squatter had been left to perish in the desert. As ever, Seekings expressed the reality of war in the bleakest terms: “We shouted to them to hang on, but we couldn’t stop to pick them up…We’d got a job to do. We couldn’t stop and mess that up.”