Reluctant Genius (2 page)

Authors: Charlotte Gray

Eliza Symonds Bell captured the closeness of her three sons (Alec is on the right) in an early watercolor

Eliza and Melville’s marriage was a happy and long-lasting union, although Eliza was ten years older than her husband and too deaf to hear much of his stirring renditions of passages from great authors. (Melville was said to read Charles Dickens better than Dickens himself. When the elders of his church rebuked him for promoting the “ungodly Mr. Dickens,” Melville stalked out of their presence, vowing that he would never darken the church’s door again. He kept to his word.) A year after their 1844 wedding, their eldest child, Melville, or “Melly,” arrived. Alexander was born two years later, and Edward, the youngest, the following year. Eliza Bell depicted her three sons as curly-haired angels in a watercolor she painted when the boys were still small: Melly is a scholarly young man, Edward is a delightful little boy in skirts, and Alexander is a lively youngster taking aim with an arrow at an invisible target. The boys may have been angelic to their mother, but to their neighbors they were rambunctious, noisy lads, always shouting and banging doors as they rushed in and out of the house. Alec asserted his independence early. Exasperated by being the third Alexander Bell in a row, he decided to add Graham to his own name, becoming “Alexander Graham Bell,” after he met a Canadian student of his father called Alexander Graham.

Alec was born in a flat in 16 South Charlotte Street, but soon after his birth his family moved first to a larger apartment, around the corner at 13 Hope Street, and then, when he was six, to 13 South Charlotte Street. This was a spacious four-story house that the Bells were able to purchase thanks to Melville’s success as a lecturer and teacher. Melville, Eliza, and their three sons occupied the ten rooms on the top two floors, and the lower two floors were rented to tenants. The house was just off Charlotte Square—an elegant Georgian square in the city’s New Town. By 1847, New Town was hardly new (its pale yellow-gray sandstone terraces had been planned nearly a century earlier and largely completed around 1820), but it was far more modern than the dark, cramped medieval buildings of the Old Town, clustered at the foot of Edinburgh Castle. When young Alec threaded his way through the Old Town’s twisting alleys and closes, he would see on each side decaying stone tenement buildings, often ten or twelve stories high, crammed with people from every walk of life—from supreme court judges to street vendors. Pigs and dogs ran freely, and sanitation was nonexistent. He had to sidestep the great clots of tubercular spittle flecked with blood that passersby casually spat onto the cobbles, and he had to keep a watchful eye on the windows above him. Edinburgh pedestrians all knew that the cry of “Gardy loo!” (a Scots approximation of the French “Prenez garde à l’eau”) meant that a chamber pot was about to be emptied on their heads from an overhead window. The odors of garbage, sewage, and coal fires had earned for the Scottish capital the nickname “Auld Reekie.”

Melville Bell was an early enthusiast of photography:Alec (on left) disliked sitting still for family portraits

In the more salubrious streets of New Town, half a mile from the castle, the Bell household was cheerful and busy, with regular visits from an extended network of relatives and friends. Eliza Bell supervised her children’s education, and when her sons were small, she played the piano for family sing-alongs, aided by a special ear trumpet attached to the instrument’s sounding board. By the time he was ten, Alec had taken over as the family’s pianist. He and his two brothers also excelled at entertaining guests, often with voice tricks. They crowed like cocks, clucked like hens, or performed as ventriloquists, making puppets recite nursery rhymes. Their cousin Mary Symonds recalled how Alec “used to chase an imaginary bee around the room, imitating the buzzing of the bee, and then the muffled sound when it seemed to be caught in the hand.”

But Alec was also a typical middle child, sandwiched between a brainy elder brother, who carried off several school prizes and on whom his father doted, and a sickly younger brother whose health dominated his mother’s attention. Despite his ready laugh, his face wore a quizzical expression in repose, and his deep-set black eyes were serious and intense. He could ham it up at parties, but he was not by nature gregarious: he often retreated into solitude, particularly when he was preoccupied with a project. “He was a thoughtful boy,” in the words of Mary Symonds, “always courteous and polite.” He was particularly sensitive to his mother’s hearing problems, which threatened to cut her off from everyday communication. In addition to communicating with her by speaking close to her forehead, he had mastered the English double-hand manual alphabet, so that he could silently spell out conversations to her. When relatives and friends gathered at the Bells’ dining-room table, all chattering at once and clattering their plates and forks, Alec would sit attentively at Eliza’s side, spelling out to her with his fingers what various people were saying so that she never felt left out. Thanks to his close relationship to his mother, Alec was untouched by the assumption, common at the time, that somehow deafness involved intellectual disability.

Alec’s relationship with his father was more complicated: throughout his life, he would be torn between a gnawing hunger for Melville’s approval and resentment of his domineering manner. Melville Bell was an authoritarian parent, convinced that he knew what was best for his children. When the boys were young, they tiptoed around the house while their father was present. Elocution lessons provided Melville’s bread and butter; a steady stream of stutterers and mumblers arrived at his door, looking for help. Professor Bell corrected their speech problems and prepared students for public recitals. In 1860, he outlined his theories in

The Standard Elocutionist,

which also included several literary passages arranged for public performance. The book is said to have run to 168 printings in Britain and to have sold a quarter of a million copies in the United States by 1892. The author frequently boasted of his success, before grumbling that he had never received from his publishers the royalties he was owed. However,

The Standard Elocutionist

did give him the credibility to become a regular lecturer at the University of Edinburgh.

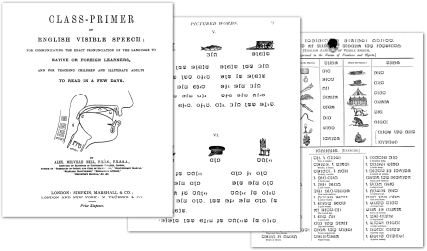

Elocution lessons, however, were not Melville Bell’s abiding interest. He was particularly fascinated by phonetics—the way the human voice actually produces sounds. When young Alec stood outside his father’s study, he often heard the oddest grunts and hisses emanating from it. When he opened the door, he would find bushy-bearded Melville, his stern brow knit in concentration, staring at his reflection in the mirror as he contorted his tongue, jaw, and lips into strange expressions, uttered a sound, then made a rapid sketch of his mouth. Melville’s pride and joy was “Visible Speech,” a series of symbols he had developed to denote different sounds. The basic symbol for each consonant was a horseshoe curve, and that of a vowel a vertical line. How Melville wrote these symbols depended in each case on the particular action of the tongue, the breath, and the lips—so as he wrote, he would constantly emit different sounds and check his reflection. There were modifying symbols, such as hooks and crossbars, to signify particular vocal positions, and additional symbols for actions like suction and trilling. Melville Bell spent years cataloging every sound a human mouth could make and devising a way to put them on paper. The culmination of his work would be

Visible Speech: The Science of Universal Alphabetics,

which he would publish in 1867. Anyone who mastered his Visible Speech symbols, he claimed, could reproduce any sound exactly, even if he or she had never heard it before and had no clue what it meant.

Melville Bell’s Visible Speech system made it possible to transcribe, and reproduce any sound a person could make.

Melville Bell’s efforts to systemize speech, while seemingly abstruse, were typical of the intellectual fervor of the mid-nineteenth century—a time when human knowledge seemed to be expanding exponentially as the world was shrinking. Steam power, which had launched the Industrial Revolution, had speeded up travel within and between continents. Trains traveled five times faster than the fastest stagecoach, and steamships had cut the average duration of a transatlantic crossing from forty to twelve days. Melville Bell was not the only Victorian eager to chart the unknown. Intrepid missionaries and explorers spread out to every corner of the globe, intent on mapping the vast areas still left blank in their atlases and on making contact with the heathens

(always

heathens, in the Victorian view) who inhabited them.

In southern Africa, David Livingstone slogged north from Cape Town, preaching the Gospel despite being maimed by a lion and felled by swamp fever. In northern Africa, Richard Burton rode off into the desert, determined to find the source of the Nile. These explorers met a bewildering array of hitherto unknown peoples and tribes, speaking different languages. But they could rarely communicate with them, as these languages were unknown and in some cases lacked their own alphabets. For nearly a century, voice experts had tried to construct a written phonetic system that could be used to transcribe any language from anywhere in the world. Now, Melville Bell announced proudly, he had achieved a workable system. He was convinced that his book would bring him both fame and fortune.

While his father was perfecting his elaborate system of curves and hooks, Alec attended Edinburgh’s Royal High School, the most important school in Scotland. When it was built in 1829, everything Greek was in fashion, and the school was modeled on the Temple of Theseus in Athens. The city could boast as graduates several stars of the Scottish Enlightenment, including philosopher David Hume, political economist Adam Smith, and writers Robert Burns and Sir Walter Scott. This intellectual explosion prompted Edinburgh to style itself “the Athens of the North.” But Alec wasn’t particularly interested in Athens, and despite Scotland’s impressive record of inventors and engineers (the Glaswegian instrument-maker James Watt commercialized the steam engine in the 1770s), the Royal High School neglected the sciences, Alec’s favorite subjects. So, to his father’s dismay, Alec’s school record was unimpressive. Chronically untidy and late for class, Alec often skipped school altogether to go bird-watching on Arthur’s Seat, the rise of land just beyond Edinburgh Castle. Instead of learning Greek, he preferred to collect plants, shells, small skeletons, and birds’ eggs. For Alec, as for many boys, high school was just a distraction from more exciting pursuits. Years later he wrote rather apologetically, “I passed through the whole curriculum of the Royal High School, from the lowest to the highest class, and graduated, but by no means with honours, when I was about fourteen years of age.”

Outside the classroom, however, he demonstrated the ingenuity and single-mindedness that would shape his later career. While still a youngster, he invented not only the speaking machine but also, for a local mill-owner whose son was one of his friends, a machine for removing the husks from grain. He installed his collection of birds’ eggs, dried grasses, and fossils in one of the rooms at the top of the Charlotte Street house and announced that this was his “laboratory.” His brothers and friends were enrolled in what he grandly termed “The Society for the Promotion of Fine Arts among Boys.” Each youthful member was dignified with the title “professor” and invited to give a lecture. Alec adopted the title “professor of anatomy” and took great delight in dissecting the corpses of small creatures, including rabbits and mice, for his fellow professors’ benefit. He lost his audience, however, when he thrust a knife into the belly of a dead piglet and the foul gas trapped in its intestines was released with an eerie groan. A posse of young professors scuttled down the stairs of the tall house and out into the street.