Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World (4 page)

Read Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World Online

Authors: Jane McGonigal

Tags: #General, #Technology & Engineering, #Popular Culture, #Social Science, #Computers, #Games, #Video & Electronic, #Social aspects, #Essays, #Games - Social aspects, #Telecommunications

BOOK: Reality Is Broken: Why Games Make Us Better and How They Can Change the World

6.78Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Let the games begin.

PART ONE

Why Games Make Us Happy

One way or another, if human evolution is to go on, we shall have to learn to enjoy life more thoroughly.

CHAPTER ONE

What Exactly Is a Game?

A

lmost all of us are biased against games today—even gamers. We can’t help it. This bias is part of our culture, part of our language, and it’s even woven into the way we use the words “game” and “player” in everyday conversation.

lmost all of us are biased against games today—even gamers. We can’t help it. This bias is part of our culture, part of our language, and it’s even woven into the way we use the words “game” and “player” in everyday conversation.

Consider the popular expression “gaming the system.” If I say that you’re gaming the system, what I mean is that you’re exploiting it for your own personal gain. Sure, you’re technically following the rules, but you’re playing in ways you’re not meant to play. Generally speaking, we don’t admire this kind of behavior. Yet paradoxically, we often give people this advice: “You’d better start playing the game.” What we mean is, just do whatever it takes to get ahead. When we talk about “playing the game” in this way, we’re really talking about potentially abandoning our own morals and ethics in favor of someone else’s rules.

Meanwhile, we frequently use the term “player” to describe someone who manipulates others to get what they want. We don’t really trust players. We have to be on our guard around people who play games—and that’s why we might warn someone, “Don’t play games with me.” We don’t like to feel that someone is using strategy against us, or manipulating us for their personal amusement. We don’t like to be played with. And when we say, “This isn’t a game!,” what we mean is that someone is behaving recklessly or not taking a situation seriously. This admonishment implies that games encourage and train people to act in ways that aren’t appropriate for real life.

When you start to pay attention, you realize how collectively suspicious we are of games. Just by looking at the language we use, you can see we’re wary of how games encourage us to act and who we are liable to become if we play them.

But these metaphors don’t accurately reflect what it really means to play a well-designed game. They’re just a reflection of our worst fears about games. And it turns out that what we’re really afraid of isn’t games; we’re afraid of losing track of where the game ends and where reality begins.

If we’re going to fix reality with games, we have to overcome this fear. We need to focus on how real games actually work, and how we act and interact when we’re playing the same game

together

.

together

.

Let’s start with a really good definition of

game

.

The Four Defining Traits of a Gamegame

.

Games today come in more forms, platforms, and genres than at any other time in human history.

We have single-player, multiplayer, and massively multiplayer games. We have games you can play on your personal computer, your console, your handheld device, and your mobile phone—not to mention the games we still play on fields or on courts, with cards or on boards.

We can choose from among five-second minigames, ten-minute casual games, eight-hour action games, and role-playing games that go on endlessly twenty-four hours a day, three hundred sixty-five days a year. We can play story-based games, and games with no story. We can play games with and without scores. We can play games that challenge mostly our brains or mostly our bodies—and infinitely various combinations of the two.

And yet somehow, even with all these varieties, when we’re playing a game, we just know it. There’s something essentially unique about the way games structure experience.

When you strip away the genre differences and the technological complexities, all games share four defining traits: a

goal

,

rules

, a

feedback system

, and

voluntary participation

.

goal

,

rules

, a

feedback system

, and

voluntary participation

.

The

goal

is the specific outcome that players will work to achieve. It focuses their attention and continually orients their participation throughout the game. The goal provides players with

a sense of purpose

.

goal

is the specific outcome that players will work to achieve. It focuses their attention and continually orients their participation throughout the game. The goal provides players with

a sense of purpose

.

The

rules

place limitations on how players can achieve the goal. By removing or limiting the obvious ways of getting to the goal, the rules push players to explore previously uncharted possibility spaces. They

unleash creativity

and

foster strategic thinking

.

rules

place limitations on how players can achieve the goal. By removing or limiting the obvious ways of getting to the goal, the rules push players to explore previously uncharted possibility spaces. They

unleash creativity

and

foster strategic thinking

.

The

feedback system

tells players how close they are to achieving the goal. It can take the form of points, levels, a score, or a progress bar. Or, in its most basic form, the feedback system can be as simple as the players’ knowledge of an objective outcome: “The game is over when . . .” Real-time feedback serves as a

promise

to the players that the goal is definitely achievable, and it provides

motivation

to keep playing.

feedback system

tells players how close they are to achieving the goal. It can take the form of points, levels, a score, or a progress bar. Or, in its most basic form, the feedback system can be as simple as the players’ knowledge of an objective outcome: “The game is over when . . .” Real-time feedback serves as a

promise

to the players that the goal is definitely achievable, and it provides

motivation

to keep playing.

Finally,

voluntary participation

requires that everyone who is playing the game knowingly and willingly accepts the goal, the rules, and the feedback. Knowingness

establishes common ground

for multiple people to play together. And the freedom to enter or leave a game at will ensures that intentionally stressful and challenging work is experienced as

safe

and

pleasurable

activity.

voluntary participation

requires that everyone who is playing the game knowingly and willingly accepts the goal, the rules, and the feedback. Knowingness

establishes common ground

for multiple people to play together. And the freedom to enter or leave a game at will ensures that intentionally stressful and challenging work is experienced as

safe

and

pleasurable

activity.

This definition may surprise you for what it lacks: interactivity, graphics, narrative, rewards, competition, virtual environments, or the idea of “winning”—all traits we often think of when it comes to games today. True, these are common features of many games, but they are not

defining

features. What defines a game are the goal, the rules, the feedback system, and voluntary participation. Everything else is an effort to reinforce and enhance these four core elements. A compelling story makes the goal more enticing. Complex scoring metrics make the feedback systems more motivating. Achievements and levels multiply the opportunities for experiencing success. Multiplayer and massively multiplayer experiences can make the prolonged play more unpredictable or more pleasurable. Immersive graphics, sounds, and 3D environments increase our ability to pay sustained attention to the work we’re doing in the game. And algorithms that increase the game’s difficulty as you play are just ways of redefining the goal and introducing more challenging rules.

defining

features. What defines a game are the goal, the rules, the feedback system, and voluntary participation. Everything else is an effort to reinforce and enhance these four core elements. A compelling story makes the goal more enticing. Complex scoring metrics make the feedback systems more motivating. Achievements and levels multiply the opportunities for experiencing success. Multiplayer and massively multiplayer experiences can make the prolonged play more unpredictable or more pleasurable. Immersive graphics, sounds, and 3D environments increase our ability to pay sustained attention to the work we’re doing in the game. And algorithms that increase the game’s difficulty as you play are just ways of redefining the goal and introducing more challenging rules.

Bernard Suits, the late, great philosopher, sums it all up in what I consider the single most convincing and useful definition of a game ever devised:

Playing a game is the voluntary attempt to overcome unnecessary obstacles.

1

1

That definition, in a nutshell, explains everything that is motivating and rewarding and fun about playing games. And it brings us to our first fix for reality:

FIX # 1 : UNNECESSARY OBSTACLES

Compared with games, reality is too easy. Games challenge us with voluntary obstacles and help us put our personal strengths to better use.

To see how these four traits are essential to every game, let’s put them to a quick test. Can these four criteria effectively describe what’s so compelling about games as diverse as, say, golf, Scrabble, and

Tetris

?

Tetris

?

Let’s take golf to start. As a golfer, you have a clear goal: to get a ball in a series of very small holes, with fewer tries than anyone else. If you weren’t playing a game, you’d achieve this goal the most efficient way possible: you’d walk right up to each hole and drop the ball in with your hand. What makes golf a game is that you willingly agree to stand really far away from each hole and swing at the ball with a club. Golf is engaging exactly because you, along with all the other players, have agreed to make the work more challenging than it has any reasonable right to be.

Add to that challenge a reliable feedback system—you have both the objective measurement of whether or not the ball makes it into the hole, plus the tally of how many strokes you’ve made—and you have a system that not only allows you to know when and if you’ve achieved the goal, but also holds out the hope of potentially achieving the goal in increasingly satisfying ways: in fewer strokes, or against more players.

Golf is, in fact, Bernard Suits’ favorite, quintessential example of a game—it really is an elegant explanation of exactly how and why we get so thoroughly engaged when we play. But what about a game where the unnecessary obstacles are more subtle?

In Scrabble, your goal is to spell out long and interesting words with lettered tiles. You have a lot of freedom: you can spell any word found in the dictionary. In normal life, we have a name for this kind of activity: it’s called typing. Scrabble turns typing into a game by restricting your freedom in several important ways. To start, you have only seven letters to work with at a time. You don’t get to choose which keys, or letters, you can use. You also have to base your words on the words that other players have already created. And there’s a finite number of times each letter can be used. Without these arbitrary limitations, I think we can all agree that spelling words with lettered tiles wouldn’t be much of a game. Freedom to work in the most logical and efficient way possible is the very

opposite

of gameplay. But add a set of obstacles and a feedback system—in this case, points—that shows you exactly how well you’re spelling long and complicated words in the face of these obstacles? You get a system of completely unnecessary work that has enthralled more than 150 million people in 121 countries over the past seventy years.

opposite

of gameplay. But add a set of obstacles and a feedback system—in this case, points—that shows you exactly how well you’re spelling long and complicated words in the face of these obstacles? You get a system of completely unnecessary work that has enthralled more than 150 million people in 121 countries over the past seventy years.

Both golf and Scrabble have a clear win condition, but the ability to win is not a necessary defining trait of games.

Tetris

, often dubbed “the greatest computer game of all time,” is a perfect example of a game you cannot win.

2

Tetris

, often dubbed “the greatest computer game of all time,” is a perfect example of a game you cannot win.

2

When you play a traditional 2D game of

Tetris

, your goal is to stack falling puzzle pieces, leaving as few gaps as possible in between them. The pieces fall faster and faster, and the game simply gets harder and harder. It never ends. Instead, it simply waits for you to fail. If you play

Tetris

, you are

guaranteed

to lose.

3

Tetris

, your goal is to stack falling puzzle pieces, leaving as few gaps as possible in between them. The pieces fall faster and faster, and the game simply gets harder and harder. It never ends. Instead, it simply waits for you to fail. If you play

Tetris

, you are

guaranteed

to lose.

3

On the face of it, this doesn’t sound very fun. What’s so compelling about working harder and harder until you lose? But in fact,

Tetris

is one of the most beloved computer games ever created—and the term “addictive” has probably been applied to

Tetris

more than to any single-player game ever designed. What makes

Tetris

so addictive, despite the impossibility of winning, is the intensity of the feedback it provides.

Tetris

is one of the most beloved computer games ever created—and the term “addictive” has probably been applied to

Tetris

more than to any single-player game ever designed. What makes

Tetris

so addictive, despite the impossibility of winning, is the intensity of the feedback it provides.

As you successfully lock in

Tetris

puzzle pieces, you get three kinds of feedback:

visual—

you can see row after row of pieces disappearing with a satisfying poof;

quantitative

—a prominently displayed score constantly ticks upward; and

qualitative

—you experience a steady increase in how challenging the game feels.

Tetris

puzzle pieces, you get three kinds of feedback:

visual—

you can see row after row of pieces disappearing with a satisfying poof;

quantitative

—a prominently displayed score constantly ticks upward; and

qualitative

—you experience a steady increase in how challenging the game feels.

This variety and intensity of feedback is the most important difference between digital and nondigital games. In computer and video games, the interactive loop is satisfyingly tight. There seems to be no gap between your actions and the game’s responses. You can literally see in the animations and count on the scoreboard your impact on the game world. You can also feel how extraordinarily attentive the game system is to your performance. It only gets harder when you’re playing well, creating a perfect balance between hard challenge and achievability.

In other words, in a good computer or video game you’re always playing on the very edge of your skill level, always on the brink of falling off. When you do fall off, you feel the urge to climb back on. That’s because there is virtually nothing as engaging as this state of working at the very limits of your ability—or what both game designers and psychologists call “flow.”

4

When you are in a state of flow, you want to stay there: both quitting

and

winning are equally unsatisfying outcomes.

4

When you are in a state of flow, you want to stay there: both quitting

and

winning are equally unsatisfying outcomes.

The popularity of an unwinnable game like

Tetris

completely upends the stereotype that gamers are highly competitive people who care more about winning than anything else. Competition and winning are

not

defining traits of games—nor are they defining interests of the people who love to play them. Many gamers would rather keep playing than win—thereby ending the game. In high-feedback games, the state of being intensely engaged may ultimately be more pleasurable than even the satisfaction of winning.

Tetris

completely upends the stereotype that gamers are highly competitive people who care more about winning than anything else. Competition and winning are

not

defining traits of games—nor are they defining interests of the people who love to play them. Many gamers would rather keep playing than win—thereby ending the game. In high-feedback games, the state of being intensely engaged may ultimately be more pleasurable than even the satisfaction of winning.

The philosopher James P. Carse once wrote that there are two kinds of games:

finite games

, which we play to win, and

infinite games

, which we play in order to keep playing as long as possible.

5

In the world of computer and video games,

Tetris

is an excellent example of an infinite game. We play

Tetris

for the simple purpose of continuing to play a good game.

finite games

, which we play to win, and

infinite games

, which we play in order to keep playing as long as possible.

5

In the world of computer and video games,

Tetris

is an excellent example of an infinite game. We play

Tetris

for the simple purpose of continuing to play a good game.

LET’S TEST OUR

proposed definition for a game with one final example, a significantly more complex video game: the single-player action/puzzle game

Portal

.

proposed definition for a game with one final example, a significantly more complex video game: the single-player action/puzzle game

Portal

.

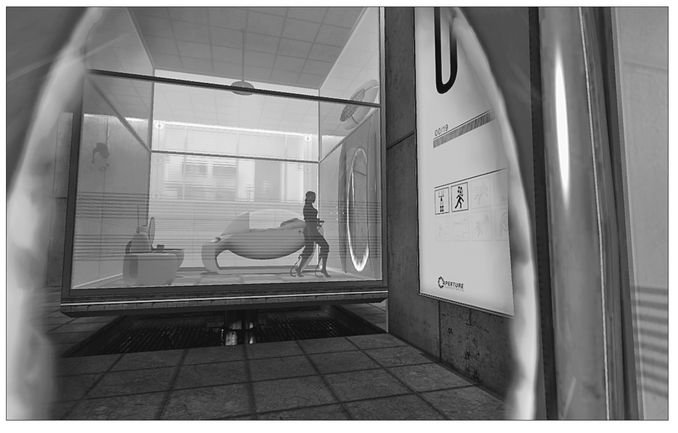

When

Portal

begins, you find yourself in a small, clinical-looking room with no obvious way out. There is very little in this 3D environment to interact with: a radio, a desk, and what appears to be a sleeping pod. You can shuffle around the tiny room and peer out the glass windows, but that’s about it. There’s nothing obvious to do: no enemies to fight, no treasure to pick up, no falling objects to avoid.

Portal

begins, you find yourself in a small, clinical-looking room with no obvious way out. There is very little in this 3D environment to interact with: a radio, a desk, and what appears to be a sleeping pod. You can shuffle around the tiny room and peer out the glass windows, but that’s about it. There’s nothing obvious to do: no enemies to fight, no treasure to pick up, no falling objects to avoid.

Other books

Sanctuary Line by Jane Urquhart

Only You by Bonnie Pega

Short-Straw Bride by Karen Witemeyer

The Tomorrow-Tamer by Margaret Laurence

Translation of Love by Montalvo-Tribue, Alice

The Whale Has Wings Vol 2 - Taranto to Singapore by David Row

Apocalypse in the Homeland: The Adventures of John Harris by Anthony Newman

The Thursday Night Club by Steven Manchester

Those in Peril by Margaret Mayhew

Alexander Hamilton by Ron Chernow