Rats and Gargoyles (9 page)

Read Rats and Gargoyles Online

Authors: Mary Gentle

"Luck," Desaguliers said, relaxing, and with a

genuine regret in his tone. "We were lucky to come out of that. No one else who

was caught in the building survived."

No through-draught moved in the room under the

rafters. A fly skewed right-angles across the air, sounding distant in the heat,

although it was only a few feet above his head. Lucas bent over the paper,

imprinting neat cuneiform characters with an ink-stylus.

I like the University well enough, sister; you’d

like it, too. Tell our father that I will stay here for the three years. It will

please him.

Candover seems very far away now.

He put the stylus down on the table. His jacket

already lay over the back of his chair; now he unbuttoned his shirt and pulled

it out of his belt. Scratching in the dark curls of his chest, he wrote:

I consulted a philosopher (which is what they call

a seer here) earlier this morning, but she could tell me nothing. She says she

will draw a natal chart for one of the other students, but it will take her a

few hours. I’ve said I’ll go back at noon.

Footsteps crossed the courtyard below. Lucas leaped

from his chair and leaned over the window-sill.

Mistress Evelian waved a greeting, gestured that

she would speak but couldn’t: mouth full of clothes-pegs. Last remnants of mist

blurred the tiled roofs. A smell of boiled cabbage drifted in. On the street

side of the room, the noise of a street-player’s lazy horn wound up into the

late-morning air.

Hugging himself, sweaty, Lucas crossed back to the

table.

Gerima, perhaps I won’t come back to Candover at

all. I might not go to the university. I might just stay here in the city.

The skylight screeched, dropping rust-flakes into

his eyes as he wedged it further open. The air up on the slanting roof hit him

like warm water, and he drew his head back inside. A bird cried.

The seer is a woman who calls herself the White

Crow. I said I would call back for the birthstar chart myself, although the

person it concerns is no friend of mine. The White Crow

—

The slow horn milked heat from the day, drowsing

all the morning’s actions away into dreams.

He scratched at the hair of his chest, fingers

scrabbling down to the thin line of back-growing hair on his belly. Sweat

slicked his fingers. The narrow room (only bed, table and cast-iron basin in it)

stifled him. Dizzy, dazed, drunk on nothing at all, Lucas threw himself down on

his back on the bed and stared up through the open window at the sky.

Imaging in his mind how her hair, that strange dark

red, is streaked with a pure silver and white, flowing from her temples. How her

eyes, when they smile, seem physically to radiate warmth: an impossibility of

fiction, but striking home now to some raw new center inside him.

Gerima, so much of her life has gone past and I

don’t know what it is. I would like to go back and make it turn out right for

her. If she laughs at me, I’ll kill myself.

The slow heat stroked his body as he stripped,

lying back on the white linen. Imaging in his mind how sweat darkens her shirt

under the arms, and in half-moons under each breast, and the contrast between

her so-fine-textured skin and her rough cloth breeches. His fingers pushed

through the curly hair of his genitals, cupped his balls for a moment; and then

slid up to squeeze in slow strokes. His breathing quickened.

A faint breeze rose above the window-sill and blew

the unfinished letter on to the floor.

On the far side of the courtyard Clock-mill struck

eleven. An authoritative knocking came on the street-door. The White Crow swore,

threw down her celestial charts and padded barefoot down the narrow stairway to

the street.

"Yes?"

A man gazed nervously up and down the cobbled lane.

A dirty gray cloak swathed him from head to heels, the hood pulled far forward

to hide his face.

"Are you the White Crow?"

The White Crow leaned one elbow on the door-frame,

and her head on her hand. She looked across at the hooded face (standing on the

last step, she was just as tall as he) and raised an eyebrow.

"Aren’t you a little warm in that?"

The air over the cobbles shimmered with heat, now

that the early mist had burned away. The man pushed his hood far enough back for

her to see a fleshy sweat- reddened face.

"My name is Tannakin Spatchet," he announced.

"Mayor of the District’s East quarter. Lady, I was afraid you wouldn’t want to

be seen receiving such an unrespectable visitor."

The White Crow blinked.

"What do you want?"

"Talismans." He leaned forward, whispering. "Charms

that warn you when the Decans’ acolytes are coming."

"No such thing. Go away. That’s not possible."

His fleshy arm halted the door as she slammed it.

"It

is

possible! A girl saved six people’s lives yesterday with such a

warning. She’s dead now. For the safety of my quarter’s citizens, I want some

talisman or hieroglyph that will give us warning if it happens again!"

The White Crow gestured with spread palms, pushing

the air down, as if physically to lower the man’s voice. She frowned. Lines at

the corners of her eyes radiated faintly down on to her cheek-bones, visible in

the sunlight.

He said: "

Is

it possible?"

"Mmm . . . Bruno the Nolan incontrovertibly proves

how

magia

runs in a great chain from the smallest particle, the smallest

stone, up to microbes, bacteria; roses, beasts and men; daemonic and angelic

powers–and to those Thirty-Six Who create all in Their divinity. And how

magia

-power may be heard and used up and down the Great Chain of Being . . ."

The White Crow tapped her thumb against her teeth.

"I use the Celestial world. Yes . . . Master Mayor,

you realize talismans can be traced to the people who made them? People who make

them, here, they don’t live long. Who sent you to me?" she temporized.

"A friend, an old friend of mine. Mistress Evelian.

She mentioned a Hermetic philosopher lodging with her . . ."

The White Crow shoved a hand through her massy

hair, and leaned out to look up and down the street. "That woman is perilously

close to becoming a philosopher’s pimp. Oh, come in, come in. Mind the—Never

mind."

Tannakin Spatchet rubbed his forehead where the low

doorway caught him, and followed her up the dark stairs.

She led him through a room with an iron stove to

one side and a scarcely less rigid bed to the other, and through into an airy

room smelling of paper and leather bindings. She held out a hand for his cloak.

"Can you help, lady?"

The White Crow folded the cloak, studying the bulky

fair-haired man. He seemed in his fifties, too pallid for health. She dropped

the cloak randomly across a stack of black-letter pamphlets.

"Mayor of the Nineteenth District," she repeated.

"Of

its East quarter. I regret coming to you in this unceremonious manner. I brought

no clerks or recorders, thinking the whole matter best kept quiet." He cleared

his throat. "Yesterday . . ."

Tannakin Spatchet touched a finger to the cleared

chair, looked distastefully at the book-dust, and seated himself gingerly. Then

he met the White Crow’s gaze, his fussiness gone.

"Yesterday I saw Decans’ acolytes," the Mayor said,

"closer than I ever hope to see them again. Five of my people are missing–dead,

I should say. I need someone to advise me."

A beast yipped. The White Crow’s preoccupied gaze

snapped back into focus. She crossed the room and squatted down, picking up from

a padded box a young fox-cub and reaching for a glass bottle. As she seated

herself on the window-sill, the reddish lump of fur in her lap stinking of

vixen, and bent her head to feed it, she said: "At a Masons’ Hall, in the East

quarter."

"You know of it?"

"Evelian told me this morning. I think she knew

someone in the hall. I knew that

something

had been destroyed." She held

out a free hand, the bandages on the palm newly bloodstained. "We respond, some

of us, to such disturbances."

The warm wind blew in at the window, easing the

fox-stink.

"What I say must go no further."

She jerked her head at the room: the books, charts,

orreries and globes. "I am what I am, messire. If you want my help, tell me

why."

"I . . . know so little," Tannakin Spatchet

confessed. "We’re not admitted to the mysteries of the halls. I heard of the

meeting only at the last moment. I and my councilors thought fit to force an

entrance. Would to god we never . . . Master Falke spoke there. Of ways to free

us from those who rule the city."

Pain ached in her palm. The fox-cub whined, nipping

sleepily at her wrist.

"Stupid!

Stupid.

What were you going to fight

Decans with, messire–your bare hands?"

"Lady, I have no proof, but I believed Master Falke

to be a secret officer in the Society of the House of Salomon–they having their

secret officers infiltrated into almost every hall."

He glanced over his shoulder at the open window.

"The House of Salomon say that since we build stone

on stone to increase the Fane’s power, then we could raze stone

from

stone, so raze the Fane and the power of the Thirty-Six with it. Could that be

so, lady?"

"In all the greater and the lesser

magias,

patterns compel."

The White Crow rubbed her knuckles along the fox-

cub’s rough coat. It opened tiny amber eyes. She yipped under her breath, very

softly, and reached down to tap a heavily bound copy of Vitruvius’

The Ten

Books on Architecture

resting on the sill.

"This House of Salomon seems to follow orthodox

teaching. Vitruvius writes that the measurements of a truly constructed building

mirror both the proportions of the human body and the shape of the universal

Order. Microcosm mirrors macrocosm; the Fane mirrors the Divine within.

Theoretically, break Their mirror and you remove Their channels of power. But we

speak of the Thirty-Six."

Tannakin Spatchet shivered. The White Crow

shrugged.

"It’s foolhardy. The Decans aren’t so easily

challenged." She spoke with the contempt of long knowledge. "They loosed the

least

of their servants on you, and—"

Tannakin Spatchet rose. "Do I look so much of a

fool? Falke called the meeting; I heard of it only by chance. Falke called in

Fellowcrafts from half the halls in the quarter;

Falke

brought in the

Rat-Lords, and a Kings’ Memory!"

"This is the Master of the Hall? And you couldn’t

stop it, Master Mayor?"

"A builder listen to any one of us! Very likely."

Deep sarcasm sounded in the Mayor’s voice. He looked down at the White Crow.

"Someone betrayed the meeting to those at the Fane. Falke’s dead. So are those

others who didn’t get out in time. If they knew who betrayed

them, I don’t."

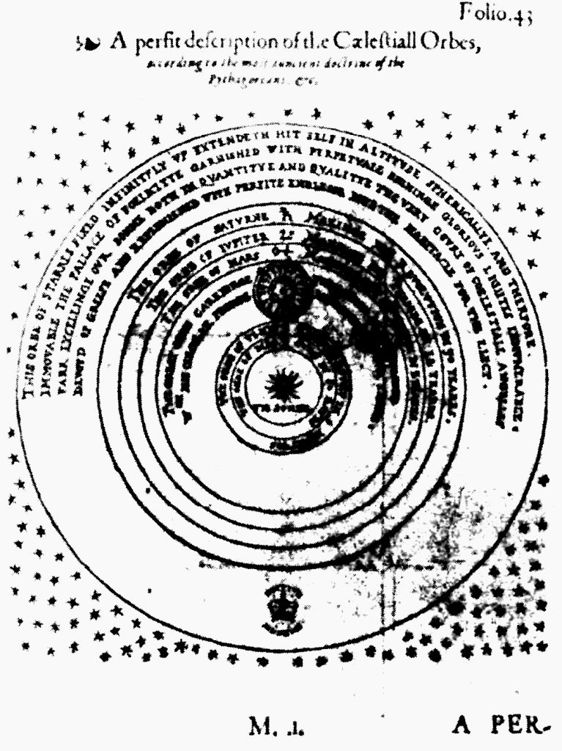

‘

In all the greater and the lesser magias,

patterns compel

’. From

A Perfit Description of the Caelestiall Orbes,

Thomas Digges, London, 1576

He wiped his forehead. "I’m sorry, lady. I’ve spent

the morning with widows and children. It isn’t easy explaining to them how I am

still alive and the others dead."

The White Crow put the fox-cub back into its box.

She brushed orange hairs from her shirt and knee-breeches, sniffed her fingers,

and wrinkled her nose. She raised her head and stared through the open window.

No dark in her vision, no taste in her mouth but sour wine.

"Decans. As if," she said, "you or I were to pour

boiling water into an ant’s nest. Does it matter if a few escape? With only a

little more effort they could cauterize the city itself, humans and Rats

together."

Tannakin Spatchet sat down slowly. He absently

began to straighten the edges of the stacked papers on the table. "What are we?

Their hands. Their

builders.

Of no more significance than a trowel, a

hod, a pair of compasses. The least we need is warning, when they exercise their

power. Lady, can you help me?"

"If I can, I will."

The determination in that seemed to surprise even

her. She stood and briskly began sorting through books on a low shelf.

"You tell me other halls were involved? And so

there’ll be more meetings . . . ?" The White Crow straightened, a hand in the

small of her back.

Tannakin Spatchet said: "Is a scrying spell

possible?"

She looked questioningly at him.

"To discover who betrayed them to the Decans," the

Mayor amplified. "And why."

"More difficult. I can try. Tell me, first, who was

there. Who was in the hall when it was destroyed."

The White Crow looked out into the courtyard, and

saw Mistress Evelian, golden hair shining in the sun, pegging out washing; and

holding a shouted conversation with the dark-haired student, Lucas, at his attic

window.