Radio Free Boston (27 page)

Authors: Carter Alan

The experimental attitude was, perhaps, best exemplified by the

WBCN

Rock 'n' Roll Rumble, an annual event in which the station sought to crown Boston's best up-and-coming band from a field of two dozen contenders. The local competition, spread out over nine nights, was the brainchild of Bieber, who launched a prototype of the contest in 1978 at the Inn-Square Men's Bar in Cambridge. “Eddie Gorodetsky and I came up with the original concept. We didn't want to call it a battle of the bands, and in one of our brainstorming sessions we arrived at the title, which was sort of linked [pun intended] to the Link Wray song [1958's instrumental âRumble'].” By 1979, the competition had shifted over to the Rat in Kenmore Square for its official first year. “The Boston music community was coming into its own,” Bieber continued. “We started out very primitively in 1978, but there was a natural growth and progression of Boston bands that advanced through '79 and '80. We started doing T-shirts, printing supplements [in the

Phoenix

], and putting together consequential prize packages that would be worthwhile to the bands: not just money, but recording time, makeovers, equipment, and advertising space.” Various sponsors also climbed on board over the years to offer significant prizes to the winners and also kick in the cash that allowed Bieber much greater clout in placing the station's local advertising for the competition. Ironically, one of those supporting sponsors was the new kid on the block that many people thought would kick

WBCN

into an early grave:

MTV

.

The 1979 Rumble awarded the best new talent prize to the popular rock trio the Neighborhoods, while 1980 would crown Pastiche in a battle

branded by the local media as a victory for new wave over heavy metal, as the hard-rocking France was defeated. The competition was not without its hiccups: one night a prankster set off a sulfur bomb in the women's bathroom, sending billowing clouds of acrid smoke into the dingy catacombs of the Rat. As bands and patrons alike fled in panic, running madly upstairs into the street, a somewhat-dazed Ken Shelton lingered on, nearly hidden in the smoke at the judges' table, holding his ballot and a couple of remaining free-drink tickets. “Is there a fire?” he asked torpidly, before being shooed out the door. When the Rumble had moved to its new home at Spit and Metro a couple years later, an incident involving a high-powered record label VP threatened to give

WBCN

a media black eye. The executive, serving as a judge, was caught by a local newspaper reporter out on Lansdowne Street trying his best pickup lines on a pretty lady while the bands toiled inside.

WBCN

publicly banished the indifferent and intoxicated exec from the competition, and then threw out his scores.

That the writers from such newspapers as the

Boston Globe

,

Herald

,

Phoenix

,

Sweet Potato

,

Boston Rock

, and enduring local rag the

Noise

would devote significant space to covering the Rumble, also serving regularly on the judges panel, ensured tremendous exposure for budding artists who starved for such attention. As the event gathered steam over succeeding years, the music industry sent streams of talent scouts into Boston to size up prospects from each new list of two dozen hopefuls. “For a Boston music fan, it's an opportunity to sample the sounds of the up-and-coming bands,” Jim Sullivan reported in the

Boston Globe

in May 1991 (when the Rumble fielded its thirteenth year of competition). “Win or lose, it's a chance to be seen by the record company honchos. That is, after all, the main idea from a band's point of view.”

“A lot of our bands went on to get record label deals. âTil Tuesday was a prime example of that,” Mark Parenteau pointed out about 1983's Rumble-winning contestant, which impressed the scouts sent to the competition from Epic Records. Within a year, the quartet, led by singer/songwriter/ bassist Aimee Mann, had signed a recording contract and in early 1985 released its debut album,

Voices Carry

, which eventually sold over five hundred thousand copies. After two more âTil Tuesday albums, Aimee Mann embarked on a solo career that she has sustained ever since. Albert O, who joined the

WBCN

air staff in July 1982, soon became involved in organizing the annual contest. “Some of the best bands didn't win, ones that

all went onto national fame,” he observed. “How about the Del Fuegos, Big Dipper, the Lemonheads?” The Del Fuegos, which signed to Slash Records and eventually Warner Brothers, became a much-beloved and influential alternative “roots” band in America for years to come, but in 1983, the group never even won its Rumble semifinal round.

I remember stepping up on stage at Spit at the end of the night to announce the winner. After witnessing four bands, everyone in the audience was well lubed, bellowing out their encouragements and insults, most chanting the name “Del Fuegos!” . . . “Del Fuegos!” . . . Embarrassing emcee situation number 1: the microphone won't work. Well, it didn't, and after a couple of moments of just dying up there, I jumped down and ran through the rowdy crowd into the DJ booth to use that mike. Perched a few steps above the dance floor in a small cupola, the booth might have made it harder for people to see me, but it also provided a greater measure of protection. Good thing, because as soon as I yelled, “The winner is . . . Sex Execs!” the place erupted. Ice cubes were hurled in at the booth, a couple smacking me in the face. That had barely registered before I heard the sound of glass shattering on the wall. The club DJ yelled, “Down! On the floor!” He pulled the door shut and locked it. We huddled in our foxhole and didn't dare poke our heads over the lip until the lights had come on and the bouncers cleared the place out.

By the seventh annual Rumble in 1985, the finals were being held downtown at the Orpheum Theater, illustrating the exploding popularity of the Boston music scene by the middle of the decade. The competition reached a pinnacle of sorts the following year, when the stately old theater was nearly ripped open by the hardcore unit Gang Green. “They were a bunch of punk-surfing, drunken buffoons from Boston,” Mark Parenteau laughed, “But, hey, they won!” Front man Chris Doherty totaled a keyboard onstage with a sledgehammer and, for good measure, happily mooned the crowd as he walked off stage, picking up a unanimous triumph from the panel of five judges. David Bieber affirmed the decision: “I think of Gang Green up on that stage, shooting beers,” he chuckled, “that band could have been Green Day.” The happy and wanton amalgam of misfit toys bashed out their thunderous sonic victory over the more commercial country-rock flavor of Hearts on Fire, whose guitarist, Johnny A, well remembered the night: “It felt almost like Good vs. Evil, because they were such punks and abrasive guys, and we were musicians just trying to write good music. So,

we lost and, I guess, Evil triumphed!” he laughed. “But, it was a big deal to be playing the Orpheum Theater, and it was a great music scene back then. I miss that.” After the finalists had performed, and while the audience waited for the votes to be tallied, the Rumble tradition of presenting a surprise guest artist each year was fulfilled by Peter Wolf and also (the famously nonwinning) Del Fuegos.

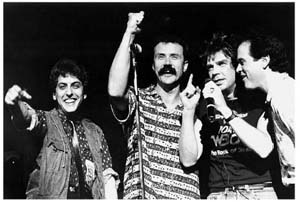

Announcing the 1986 Rumble winners from the Orpheum stage. (From left) Steve Strick, Dan McCloskey, Carter Alan, and Albert O. Photo by Leo Gozbekian.

As far as sheer attendance numbers went, this would be the high water mark for the Rumble, the finals remaining in the Orpheum for three years before moving back into the nightclub atmosphere of Metro and then the Paradise Theater, the Middle East in Cambridge, and Harper's Ferry in Allston. There would be noteworthy winners who went on to fame: Tribe, the Dresden Dolls, Heretix, and Seka (which changed its name to Strip Mind and featured Godsmack founder Sully Erna), but the central idea always remained the same: focus on the music, no matter what the style and no matter which venue it was presented in. The Rock 'n' Roll Rumble became one of

WBCN'S

most enduring traditions, surviving even beyond the station's

FM

radio sign-off. In 2011, local music maven and former '

BCN

jock Anngelle Wood resurrected the event after a one-year absence, holding the thirty-second contest at TT the Bears in Cambridge under the

auspices of classic rock sister station

WZLX-FM

and the surviving

HD

-radio and streaming versions of “Free Form '

BCN

.”

As the decade got into gear and

WBCN

assumed its new positioning identity as “The Rock of Boston,” there were a lot of new faces standing at the bar on those Rumble nights at Spit. Tracy Roach had decided to move on in 1980, and Lisa Karlin, drafted from crosstown '

COZ

to do evenings, would remain for two years. The “Duke of Madness” left as well, cut loose by the station after an altercation he had with Charles Laquidara early one morning as the “Big Mattress” crew sleepily arrived to set up the day's show. Neither DJ remembers too much about the argument, but Jerry Goodwin did recall, “There was a wonderful camaraderie amongst the people who worked there, [but] Charles and I were always at each other's throats. I'd rag him all the time about his nonprofessionalism.” For years, radio folklore held that the two jocks had a knock-down, drag-out fight in the air studio as the overnight host left and '

BCN'S

morning maniac took his place. The tale got taller as time went by: one of them choked the other against the studio wall, one flew through the air like that guy in every Western who's tossed through the saloon window in a shower of glass. “That wasn't it at all, man,” Goodwin corrected, stating that there were only words between the pair. “It's reasonable to say,” he smiled, “that there were professional egos in the way”âthat, and perhaps some controlled substances as well.

“It was verbal; no one hit each other,” confirmed Bill Kates, Goodwin's producer. “Frankly, it was really a kind of âtempest in a teacup' as far as I could see.”

“Charles said, âFuck this!' and walked out one side [of the studio] through one door, and I walked out the other,” Goodwin continued. “I lived in Back Bay, so I walked home and went to bed as usual. Then I got that phone call about one o'clock in the afternoon from Oedipus: âGet to the station right now!' Only then did I realize that Charles had kept walking too and he had not gone on the air. Poor Bill Kates had to take over the show. There were two doors in that studio; we both went out each one, and ânever the twain shall meet.'” Since no licensed operator remained on the station premises, an

FCC

regulation had been breached, and Goodwin, still signed in on the transmitter log when he abandoned ship, took the fall. Goodwin's departure meant that I finally got a full-time position, as I replaced him in the weeknight 2:00 a.m. slot. Six months later, Oedipus would move me into the 6:00 to 10:00 p.m. shift, which I'd occupy for nearly four years.

A young and boisterous crowd of “weekend warriors,” who would take important supporting roles in the subsequent decade, appeared: Dave Wohlman, Carla Raczwyk (known as “Raz on the Radio”), Albert O, Carla Nolin, Carmelita, and Lisa Traxler. New jocks were given their own silver satin

WBCN

jackets with their name embroidered on the front. “As gaudy as it was,” Dave Wohlman remembered, “that was a symbol that you made it; that you were there! What a point of pride: a manifestation that it wasn't a pipe dream, you were actually a part of the staff.” The satin would disappear later in the eighties, but not the pride, as Oedipus ordered a new set of custom leather jackets to replace the silvery velvetiness of the seventies model. After four failed audition tapes Brad Huckins finally got his leather prize and was redubbed “Bradley Jay” on the air, a talent destined to be the final DJ on

WBCN

many years later. One other notable weekend warrior of the time was longtime Boston radio veteran John Garabedian, who joked in 1983 that he was “a semi-legend.” But that statement actually rang true: as a star of 1960s

AM

radio in Worcester at

WORC

and Boston on

WMEX

. Garabedian's up-tempo, listener-proactive style would soon endear him to viewers of his own local video channel, V66, and later the hugely successful syndicated Top 40 show

Open House Party

.

Oedipus credited '

BCN'S

victory over

WCOZ

to “great announcers, plus great production. We did fun and creative things; production was always an important part of that.” From the tone and imagination going into the taping of commercials, radio station

IDS

, and promos to the “Mighty Lunch Hour” song remakes,

WBCN'S

production department underwent a major generational change as Tom Couch and Eddie Gorodetsky transitioned out after being discovered by Don Novello and relocating to Toronto to write comedy sketches for SCTV. Despite losing this gifted pair, the department didn't skip a beat, owing to the talents that took over. First on the job (some of the time) was Billy West, who would go on to become one of America's great voice talents, following in Mel Blanc's

Looney Tunes

footsteps as Bugs Bunny and Elmer Fudd; originating and starring in

Ren and Stimpy

; acting as a principle voice in

Futurama

; and, heck, he was the red M&M! But Billy West's story was one burdened by incredible personal struggles and years of pain, and to everyone around him at

WBCN

, each day seemed like it could easily be his last. West, who's been sober for decades, said, “I was just a real bad boy, cross-addicted on cocaine and alcohol . . . high voltage. Once somebody like me started drinking, there was not enough

booze on the street . . . or in the city.” But West's hours at

WBCN

resulted in some of the most memorable comedy bits that the station ever broadcast: “Y-Tel Records presents

The Three Stooges Meet the Beatles!

” and “

Popeye Meets the Beach Boys!

”; “Falk-in' Athol” (the impersonated actor touring the Massachusetts town); “Kangaroo Balls”; “Merry Christmas Boston” (a remake of the Beach Boys holiday classic); “The Rare Elvis Drug Song”; and the fictional, multihour “Fools Parade,” allegedly taking place out on Boylston Street during April Fool's Day.