Radio Free Boston (24 page)

Authors: Carter Alan

Matt Siegel's departure from

WBCN

also signaled the beginning of a thirteen-year midday dynasty for his successor. As one of the big guns at

WCOZ

, Ken Shelton had inflicted major damage on his competition, but with the departure of Clark Smidt, his relationship with Blair Radio's starchy local managers wilted. Shelton had attempted to cross the street from '

COZ

to '

BCN

with Parenteau two years earlier, but the handshake deal with Klee Dobra fell through at the last minute. Then the jock got a call from Smidt at his new station,

WEEI-FM

, working a fresh format the program director had pioneered called “soft rock.” “The Eaglesâwithout the turkeys,” “Joniâwithout the baloney,” “Moody Bluesâwithout the blahs,” and “Ronstadtâwithout wondering what tune just blew by you” were all examples of

WEEI'S

clever ad campaign. Smidt not only offered

Shelton a good-paying shift but also made him the station's music director. “I thanked Tommy [Hadges] for everything and gave my two-week notice [at '

COZ

]. Meanwhile over at '

BCN

, they were ecstatic: Shelton's gone soft!' They wrote me off.” But while Tony Berardini could be happy that Shelton wouldn't be directly competing with '

BCN

anymore, he failed to anticipate

WEEI'S

rapid rise in the ratings, with not only the expected female audience but also an alarming number of men. By February 1980, the

Boston Globe

reported that in their eighteen- to thirty-four-year-old adult demographic target,

WBCN

and

WCOZ'S

ratings had “seesawed over the past 15 months, with

WEEI-FM

now in third place.”

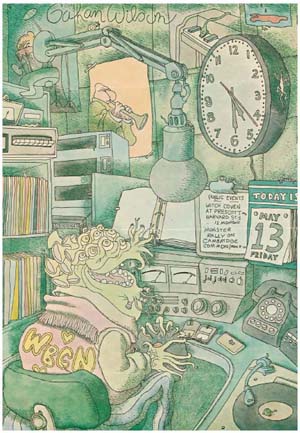

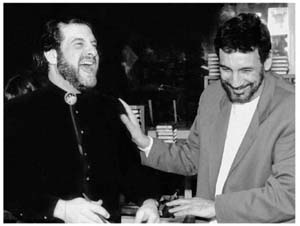

Ken Shelton, sharing a laugh with Charles Laquidara, arrives to do middays. Photo by Roger Gordy.

Ken Shelton was thrilled to be part of such an unexpected success, but his enthusiasm curdled after a year when it came time to sign a new contract. Despite substantial ratings gains, the salary windfall he expected was not put on the table by the

CBS

executives who ran

WEEI

. After negotiations failed to tweak the offer, the

DJ

opened up to friends and business associates, letting his disappointment become public. This is where fortune once again smiled on Ken Shelton. “I had an angel of good luck hanging

over me with all the timing. I got a call from David Bieber, who had been one of my first friends in Boston since 1969. I told him I was down in the dumps. He said, âNobody knows this, but Matt Siegel has given notice. I know what you went through with Charlie Kendall and Klee Dobra, but things have changed here.'” Within hours, Shelton sat at a table with Bieber, Tony Berardini, Mike Wiener, and Gerry Carrus, and this time the deal remained solid. “When I came over to '

BCN

, I knew a lot of the people there. I was a fan of them, so I stepped right in because I felt I was one of the family,” Shelton said. “That's part of the wonderfulness of

WBCN

: you felt like you were part of the family. And that's how everybody felt who listened to the stationâthey were all personal friends.” Now the workday juggernaut: Charles Laquidara, Ken Shelton, and Mark Parenteau were all firmly in place. Their presence, from six in the morning to six at night, would personify daytime radio in Boston for years to come.

That year, the radio station moved for the third time, out of the Prudential Tower and down Boylston Street to the Fenway area. Slightly more than a right-field foul from the home of the chronically pennant-less Red Sox, the rear of the one-story brick building emptied directly into an outdoor parking lot just across the street from Fenway Park. On game nights the roar of the crowds and their groans of disappointment could be heard easily at 1265 Boylston Street, where curious employees could even sneak a peek over the wall at the stats displayed on the park's jumbo screen. Mark Parenteau remembered the first time he saw the place: “Tony brought me in his Volkswagen bus to look at the property, and as we drove by, I said, âThis is perfect, Tony. We have the baseball stadium over there . . . and a gay bar across the street!'” Kidding aside, Parenteau added, “The move was an empowering thing for the station. It took '

BCN

out of that gilded tower in the clouds and put it on the street, in a neighborhood. And it became

the

entertainment neighborhood with the Red Sox right there and the Spit and Metro nightclubs [two blocks] over on Lansdowne Street.”

The new building provided plenty more space than the Prudential's submarine-like office space with its one hallway and was renovated in stages. “I was the first voice to broadcast out of the new building because they had the news department move over first,” Steve Strick mentioned. “They were still doing carpentry in there. It was comical: saws were going off while I was on the air.”

“That entire place was built by the engineering department through the

miracle of cocaine,” Mark Parenteau laughed. “You'd go over there and their eyes would be open with toothpicks, all wide-eyed and crazy, and they had been there for, like ten days straight.” As soon as the air studio had reached a sufficient state of completion, the jocks moved over during a clever live broadcast that originated in the Prudential, and then transferred to Boylston Street via Sam Kopper's Starfleet mobile studio, which was driven to '

BCN'S

new digs as Mark Parenteau handed over his shift to Tracy Roach. Kopper recalled, “We stayed on-air all the way out of the fiftieth floor, down the elevator, out the front of the Pru, and into the bus. We were literally and symbolically coming down from our perch fifty floors above Boston, back to the streets. We fired up the bus and drove slowly up Boylston Street, parade style, blowing the air horn, Bostonians cheering from the sidewalks.” Bob Demuth, an engineer who worked with Kopper, maneuvered the big Starfleet rig over to the new location, parking it out in front while scores of cars that had tailed the bus searched for similar spaces.

“Then they came into 1265,” Tom Couch remembered, “and we played a tape of my voice with the big

MGM

fanfare behind it: âTracy Roach, this is your new studio!' And she said, âIt's so nice . . . it's so big!'” It

was

big, the largest studio anyone had ever worked in, encompassing enough space to house the control board, record library, a band performance area, and a couch for guests to watch from (and fool around on). The rest of the entire station surrounded this central hub, an axis of amazing activity, and home to

WBCN

for the next twenty-five years.

One of the most significant moments at

WBCN'S

new Fenway location occurred the same year as the move. Of 8 December 1980, Oedipus recalled, “I was on the air the night John Lennon was shot and I had to read the teletype [bulletin] on the air. It was devastating. Then, I was supposed to go to a commercial. I just couldn't do it, commerce seemed so . . . meaningless. I just started playing music, and friends of mine, musicians, began calling. I told them to come on over, and they started picking records out and playing their favorite Beatles songs.” Tony Berardini was watching the Monday night football game between Miami and New England when Howard Cosell made his unforgettable announcement on

ABC-TV

. “I called Oedipus immediately and agreed with him, âDo nothing but play Beatles music; take all the commercials off the air.'”

“That's the great thing about radio; it's so immediate,” Oedipus added. “It's where people can gravitate and be together, share and hear voices,

cry and laugh.” Jerry Goodwin followed Oedipus onto the air that terrible night. As a

DJ

in Detroit in 1964, he had actually emceed for the Beatles at Olympia Stadium and sat backstage with John and Yoko at a benefit for incarcerated activist John Sinclair in 1971. “David Bieber came in, and Bill Kates, my producer, who was a musicologist in his own right, was there. The listeners called in and told me about Lennon's influence [on them], then we hustled to go find out if we had the songs they wanted. It was an amazing four-hour tribute I will never forget.”

If rock and roll could be visualized as a burning spirit, then the fire at 1265 Boylston Street was the best place to huddle for warmth and comfort. Listeners wrestled with their emotions live on the radio while '

BCN'S

employees worked through the same grief. Everyone might not have spent time with John Lennon as had Jerry Goodwin, or interviewed the man as did Mark Parenteau, but all had grown up with him. “I saw the Beatles on Ed Sullivan and I was hooked for life,” producer and future music director Marc Miller commented. Miller joined nearly all the members of the

WBCN

air staff, who hung around the station on 9 December, not knowing really what else to do. Tony Berardini said, “The whole day, we put listeners on the air, played Beatles music, and dropped all of the advertising.” Everyone pitched in to construct a broadcast tribute to John Lennon, locating documentary sound clips and recording segments for the special, including a stirring editorial from Danny Schechter, which wasn't completed until seconds before it ran on the air.

“We'd been there all day, and at some point I went to the front of the building and looked out the window,” Miller said. “There were all these people out there with candles, all singing.”

“There must have been five hundred people, who had been at a candlelight vigil on the Boston Common, who walked over,” Tony Berardini remembered. “There were so many standing in front of the station that they blocked Boylston Street. We had been talking about our Lennon retrospective tribute all day; they wanted to hear it, but we had no speakers outside on the building.”

“So Tony and I went out there,” Miller continued, “and we sort of said [to the crowd], âWe know, we feel it too . . .'”

“The two of us grabbed a couple of boom boxes and stood on the steps of the radio station holding them up in the air so people could hear the special.”

WBCN

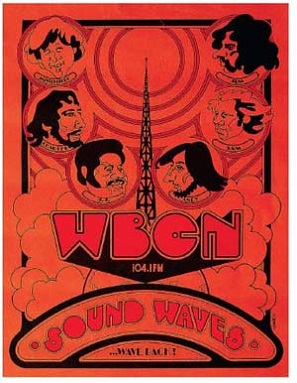

“Soundwaves” poster from 1970 featuring caricatures of “Mississippi Harold Wilson” (Joe Rogers), Charles Laquidara, JJ Jackson, Andy Beaubien, Sam Kopper, and Jim Parry. Poster art by Paul Bernath, photo of poster by Don Sanford.

WBCN

“Stereo Rock” bumper sticker from 1971. Photo by Dan Beach.