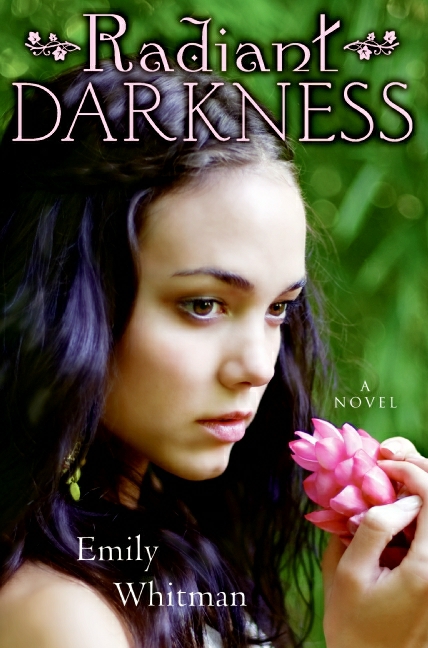

Radiant Darkness

Authors: Emily Whitman

Tags: #Juvenile Fiction, #Girls & Women, #Legends; Myths; Fables, #Greek & Roman, #Love & Romance

Table of Contents

Prologue

"PERSEPHONE.

Daughter of

DEMETER,

the harvest god

dess. Kidnapped and forced to—"

Daughter of

DEMETER,

the harvest god

dess. Kidnapped and forced to—"

Wrong! In every book of myths, the same; in every book, wrong!

Oh, I know it all got complicated because of the choices I made. I'm not trying to pretend I'm blameless.

Still, after thousands of years, I wish people knew what really happened when I walked in my mother's flowering vale and the black horses landed, crushing flowers and filling the air with heady perfume.

Just once I'd like to set the record straight.

PART ONE

Above

I hate eternity.

The Problem with Immortality

"S

tay here, Persephone," says my mother. "I have some work to do."

tay here, Persephone," says my mother. "I have some work to do."

As if I could go anywhere.

She's all dressed up in her goddess clothes—the chiton dyed purple with rare sea snails; the golden girdle embossed with waving wheat; the emeralds dripping like green leaves from her neck, her arms, her golden hair. She looks about twenty feet tall.

Off to rescue the world, probably. Mrs. Black-soilsprings-from-my-footsteps. Mrs. Even-the-grain-greets-mewith-lowered-head.

Is that what she wants me to do, bow down and worship her? That's for mortals, not me.

"I'll be back tomorrow afternoon," she says. "You'll be safe here in our beautiful vale."

Our

vale? It's

hers

. This place has nothing to do with me. It's all about

her

flowers,

her

waters,

her

rich earth.

"While I'm gone, make sure you thread the loom. And watch your yarn choice this time." She reaches up and fingers the fabric near my shoulder. "Pale colors are so unattractive with your black hair."

She's always giving me advice.

It's not like it used to be when I was little. Back when she still smiled at me. When she didn't always pinch her mouth like she's trying to keep her temper trapped inside. I remember sitting by her knee, watching her nimble fingers turn fleece into long, silky threads. "Coax fine cloth from fresh wool," she used to say in her flowery way.

But these days her advice isn't about teaching me things. It's about tamping me down, squashing me into the right shape, like a potter slaps clay around until it's his idea of a beautiful vase.

I could take it for a day, or a week, or a month. But we're immortal.

Here's the problem with immortality. Every day is exactly the same. I'm stuck forever with my mother telling me to comb my hair, put my clothes away, stand up straight. I always sleep in the same bed. I always walk by the same olive trees down to the same lake, its pebbles worn smooth by an eternity of lapping water.

My mother bends to fix her sandal strap and catches sight of my legs. She comes up with a disapproving expression. "That dress is too revealing, dear. Go change."

"But—"

She doesn't wait to listen. Turning to leave, she calls over her shoulder, "And remember not to step on the thyme: it's blooming."

As if I hadn't noticed.

Why should she care if my dress is too revealing? She's created a world devoid of men. The only men I see are painted on vases. The only men I hear about are in the stories my friends tell.

I've spent my whole life here. I'm sick of it.

The Meadow

I

wake to a new smell in the air, not the everyday overripeness of summer, but something bright and fresh, like the first spring bud bursting open. The scent is so strong, I look to see if my mother has placed a vase of flowers by my bed, but the top of my trunk holds only the usual bronze mirror and the same old red clay foxes, and the house is silent. Then I remember: my mother, leave me a gift? Not likely. She's gone to bless the fields. I decide to follow the scent and see what flower is calling to me with such a loud voice.

wake to a new smell in the air, not the everyday overripeness of summer, but something bright and fresh, like the first spring bud bursting open. The scent is so strong, I look to see if my mother has placed a vase of flowers by my bed, but the top of my trunk holds only the usual bronze mirror and the same old red clay foxes, and the house is silent. Then I remember: my mother, leave me a gift? Not likely. She's gone to bless the fields. I decide to follow the scent and see what flower is calling to me with such a loud voice.

On the trail down to the lake, I stop and sniff, trying to decide which way to turn. The well-worn path is already toasty under my soles. Dust rises in the heat and the early-morning sun soaks into my skin as if it were midday. A tortoise plods along beside the path, one heavy foot in front of the next. He stops to nibble some rosemary leaves, releasing a burst of their sharp smell. A rustle behind me makes me turn. It's only a deer. She stares at me with huge, knowing eyes.

I can smell the leaves and flowers pulling in light from the sun, releasing their own perfume in return—roses, sage— the familiar smells of home trying to take over and distract me from their new rival. Then, suddenly, a faint branching appears in the trail. There, to my left, is a small path I've never noticed. As soon as I see it, the fresh scent grows stronger, winning the battle for my attention again, and I head up the slope in a new direction. Why have I never come this way before?

The dusty path gives way to soft grass under my feet. The trail is only the faintest line now, a whisper of deer hooves, as I walk into the shade of linden and poplar trees, and the deep green of olive leaves on gnarled branches. The perfume is stronger with every step, and I feel like I'm being reeled in on a string. My breath grows shorter and faster. It must be the steep trail making my heart beat so hard.

Now plum trees, thick with ripening fruit, block my view. I lift a heavy branch from the trail and the air lightens, as if a hand were lifting a veil from my eyes. A meadow spreads out before me, but I barely look at it—I only have eyes for the flower beckoning a few steps away. A gentle white head bobs on a slender stalk, sweet and unassuming, like a daffodil's little sister. But her perfume blares out so insistently, I almost feel drugged, like I'm in a different world. In a trance, I reach toward the stalk, and the wind blows my hair back.

Wind? There's no wind today.

I lift my head, and my mouth gapes open. Four gigantic black horses are treading air above the meadow, pushing great gusts with feathered wings. Their heads toss atop massive, muscular necks. Behind them, a golden chariot blazes in the morning sun. A hand holds the reins. A strong, wide hand. A man's hand.

Who is he? What is he doing here?

I freeze, except for my heart: it's crashing around in my chest loud enough for the whole world to hear. What if that man hears and sees me staring at him? A shiver of fear runs down my spine.

He must have pulled on his reins because the horses are landing, their mighty hooves touching down as lightly as a sigh, black wings folding gently over strong, broad backs.

I pull my eyes away and stare at the ground as if it could swallow me up and make me invisible: the long, heavy grasses; a small frog hiding under a leaf, its chest rising and falling almost as quickly as mine.

Suddenly, two birds burst into raucous song, shattering my trance, and I remember I'm capable of moving. I edge back under the trees. Once I'm hidden again, I start running, quietly at first, then faster and faster, until I'm shoving branches out of my way and trampling right over poppies, scattering their blood-red petals across the path. A pounding, like drums, sounds an alarm in my ears.

When I reach the fork in the trail, I screech to a stop, panting and clutching my sides. And listening. But I don't hear anything, except my heart trying to break out of my ribs.

My mother is going to kill him! She's going to kill me!

But I ran, didn't I? Like she would tell me to. I barely glanced at him. So I must be imagining that bold, straight nose. The black beard framing strong cheeks. And those eyes. I'm probably making them up, those black eyes burning like coals in the hottest part of the fire.

The deer pokes her head out from behind a branch, then turns and ambles down the path as if nothing happened. I follow, but I'm seeing the texture rippling in his hair, the travel cloak draped over one bare shoulder, a hand pulling easily on the reins.

Maybe he came to visit my mother.

Ha! Seeing him must have addled my brain. My mother, welcome a man?

I lift my eyes from the trail. There's the lake, as blue and placid as ever. Ringing the lake are meadows stuffed with flowers and trees bowing heavy with fruit. And surrounding it all—I look up and there they are—cliffs, towering pink in the morning light. They're the prettiest prison walls you ever saw.

And my mother did it all for me.

When I was born, she always says, she still had festivals and harvests, and I would have been in her way. So she created this all-female sanctuary, calling to nymphs—flowers and trees, breezes and streams—and they came gladly, filling the vale with music and perfume. At first some of them were my nurses; now others are my friends.

Without any men around, my mother figures I'm safe and she can ignore me. She dons her harvest goddess clothes and heads off to her temples. Or she just wanders oblivious, drunk on germination, among grapevines and lemon trees.

I bet she thinks if I'm not around men, I'll never have to grow up.

I look down at my hands. I'm not voluptuous and golden like my mother, with her blue eyes and small, perfect features. I'm thin and strong. My hair is a wild black mane, and my mouth is, in my mother's disapproving words, "a bit too generous."

I shiver. Clouds are starting to cover the sun and the last trace of pink disappears from the cliffs. I could climb the highest tree in the vale and still not see over to the other side.

His tunic was banded in purple. Sea-snail purple. That means he's someone important. His skin was golden brown.

She'd know who he is.

I kick a pebble and it arcs downward, like the curve of my mother's lips. It buries itself in the bushes crowding the sides of the path.

As I round the last bend, I can feel the ground pulsing with my mother's green energy. She's back already. I look down the path and there she is, by the rosemary bush, stroking a leaf with that faraway look on her face. She's changed back into the white chiton she always wears at home, and she's barefoot, feeling the earth with her feet. She's taken off all her necklaces and bracelets so they're not in the way as she plucks a grape from the vine and pops it in her mouth. Even from here I can see her smile, wiggling her toes in the grass and lifting her face to the sky with her eyes closed. She turns her hands upward, like a plant soaking up sun.

And I know I can't tell her. She'd go all tight and tense. She'd make me start a weaving marathon. Shackle me to my loom. Sit by my side all day. Looking at me.

I don't need to know who he is.

Who he was.

He won't be back, anyway.

The Sacrifice

M

y wooden doll. I wove her scarlet dress myself when I first learned to spin wool and thread it on the loom. I was new to the shuttle's dance, so the fabric is rough.

y wooden doll. I wove her scarlet dress myself when I first learned to spin wool and thread it on the loom. I was new to the shuttle's dance, so the fabric is rough.

My red clay foxes, small enough to fit in my hand.

My old spinning top.

I gather them all in a basket, carry it to my mother, and say, "I'm ready."

"Ready?" She pauses in her weaving, the shuttle frozen in midair.

"I'm ready to sacrifice my toys."

Other books

Madrigal for Charlie Muffin by Brian Freemantle

B.u.g. Big Ugly Guy (9781101593523) by Yolen, Jane; Stemple, Adam

Kindertransport by Olga Levy Drucker

Seven Wonders by Ben Mezrich

Violet (Flower Trilogy) by Lauren Royal

Spies: The Rise and Fall of the KGB in America by Harvey Klehr;John Earl Haynes;Alexander Vassiliev

Surrender the Stars by Wright, Cynthia

Shatter by Dyken, Rachel van

Daughter of the Gods by Stephanie Thornton

Havoc (Storm MC #8) by Nina Levine