QI: The Book of General Ignorance - the Noticeably Stouter Edition (17 page)

Read QI: The Book of General Ignorance - the Noticeably Stouter Edition Online

Authors: John Lloyd,John Mitchinson

Tags: #Humor, #General

616.

For 2,000 years, 666 has been the symbol of the dreaded Anti-Christ, who will come to rule the world before the Last Judgement. For many, it’s an unlucky number: even the European Parliament leaves seat no. 666 vacant.

The number is from Revelation, the last and strangest book in the Bible: ‘Let him that hath understanding count the number of the beast: for it is the number of a man; and his number is Six hundred threescore

and six

.’

But it’s a wrong number. In 2005, a new translation of the earliest known copy of the Book of Revelation clearly shows it to be 616 not 666. The 1,700-year-old papyrus was recovered from the rubbish dumps of the city of Oxyrhynchus in Egypt and deciphered by a palaeographical research team from the University of Birmingham led by Professor David Parker.

If the new number is correct, it will not amuse those who have just spent a small fortune avoiding the old one. In 2003, US Highway 666 – known as ‘The Highway of the Beast’– was renamed Highway 491. The Moscow Transport Department will be even less amused. In 1999, they picked a new number for the jinxed 666 bus route. It was 616.

The controversy has been around since the second century

AD.

A version of the Bible citing the Number of the Beast as 616 was castigated by St Iranaeus of Lyon (

c

.130–200) as ‘erroneous and spurious’. Karl Marx’s friend Friedrich Engels analysed the Bible in his book

On Religion

(1883). He too calculated the number as 616, not 666.

Revelation was the first book of the New Testament to be written and it is full of number puzzles. Each of the twenty-two letters of the Hebrew alphabet has a corresponding number, so that any number can also be read as a word.

Both Parker and Engels argue that the Book of Revelation

is a political, anti-Roman tract, numerologically coded to disguise its message. The Number of the Beast (whatever that may be) refers to either Caligula or Nero, the hated oppressors of the early Christians, not to some imaginary bogey-man.

The fear of the number 666 is known as

Hexakosioihexekontahexaphobia.

The fear of the number 616 (you read it here first) is

Hexakosioidekahexaphobia.

The numbers on a roulette wheel added together come to 666.

Not from hashish.

The earliest authority for the medieval sect called the Assassins taking hashish in order to witness the pleasures awaiting them after death is the notoriously unreliable Marco Polo. Most Islamic scholars now favour the more convincing etymology of

assassiyun

, meaning people who are faithful to the

assass

, the ‘foundation’ of the faith. They were, literally, ‘fundamentalists’.

This makes sense when you look at their core activities. The Al-Hashashin, or Nizaris as they called themselves, were active for 200 years. They were Shi’ite muslims, dedicated to the overthrow of the Sunni Caliph (a kind of Islamic king). The Assassins considered the Baghdad regime decadent and little more than a puppet regime of the Turks. Sound familiar?

The sect was founded by Hassan-i Sabbah in 1090, a mystic philosopher, fond of poetry and science. They made their base at Alamut, an unassailable fortress in the mountains south of the Caspian Sea. It housed an important library and beautiful gardens but it was Hassan’s political strategy that

made the sect famous. He decided they could wield huge influence by using a simple weapon: terror.

Dressed as merchants and holy men they selected and murdered their victims

in

public, usually at Friday prayers, in the mosque. They weren’t explicitly ‘suicide’ missions, but the assassins were almost always killed in the course of their work.

They were incredibly successful, systematically wiping out all the major leaders of the Muslim world and effectively destroying any chance of a unified Islamic defence against the Western crusaders.

What finally defeated them was, ironically, exactly what defeated their opponents. In 1256 Hulagu Khan assembled the largest Mongol army ever known. They marched westward destroying the assassins’ power base in Alamut, before sacking Baghdad in 1258.

Baghdad was then the world’s most beautiful and civilised city. A million citizens perished and so many books were thrown into the river Tigris it ran black with ink. The city remained a ruin for hundreds of years afterwards.

Hulagu destroyed the caliphs and the assassins. He drove Islam into Egypt and then returned home only to perish, in true Mongol style, in a civil war.

Murder.

In the early nineteenth century, there was a big increase in the number of students of anatomy. The law in Britain specified that the only corpses that could be legally used for dissection were those of recently executed criminals. This was quite an advance on the anatomy lessons in Alexandria in the

third century

BC

, where criminals were dissected while still alive.

The number of executions was inadequate to supply the demand and a brisk trade grew up in illicit grave robbing. Its practitioners were known as ‘resurrection men’.

Burke and Hare were more proactive; they just murdered people and sold the bodies to an anatomist named Knox on an ‘ask no questions’ basis. In all, they killed sixteen people.

When suspicion fell on them, Burke and his wife Helen tried to get their story straight before they were separated to be interviewed by the police. They agreed to say that a missing woman had left their house at seven o’clock. Unfortunately, Mrs Burke said 7 p.m. and Mr Burke 7 a.m.

In return for his own immunity, Hare gave evidence against the Burkes. Burke was executed in 1829 but Helen got off ‘not proven’ and promptly vanished. Mr and Mrs Hare also disappeared, and Knox escaped prosecution altogether.

The father of systematic dissection was a sixteenth-century Belgian anatomist called Andreas Vesalius. He published his findings in the classic seven-volume text

On the Fabric of the Human Body.

In those days, dissection was forbidden by the Catholic Church, so Vesalius had to work in secret. At the University of Padua, he built an ingenious table in case of unexpected visitors. It could be quickly flipped upside down, dumping the human body underneath and revealing a splayed-open dog.

Over the last twenty years, dissection has fallen out of favour in medical schools – the victim of overly packed curriculums, a shortage of teachers and a general sense that it’s an antiquated chore in a high-tech world.

It’s now possible to qualify as a doctor without ever having dissected a body at all. To save time and mess, students study ‘prosections’ – bodies that have already been professionally dissected – or computer simulations that do away with cadavers entirely.

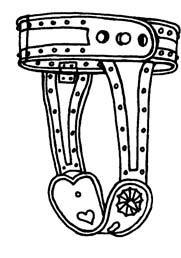

The idea of a crusader clapping his wife in a chastity belt and galloping off to war with the key round his neck is a nineteenth-century fantasy designed to titillate readers.

There is very little evidence for the use of chastity belts in the Middle Ages at all. The first known drawing of one occurs in the fifteenth century. Konrad Kyeser’s

Bellifortis

was a book on contemporary military equipment written long after the crusades had finished. It includes an illustration of the ‘hard iron breeches’ worn by Florentine women.

In the diagram, the key is clearly visible – which suggests that it was the lady and not the knight who controlled access to the device, to protect herself against the unwanted attentions of Florentine bucks.

In museum collections, most ‘medieval’ chastity belts have now been shown to be of dubious authenticity and removed from display. As with ‘medieval’ torture equipment, it appears that most of it was manufactured in Germany in the nineteenth century to satisfy the curiosity of ‘specialist’ collectors.

The nineteenth century also witnessed an upturn in sales of new chastity belts – but these were not for women.

Victorian medical theory was of the opinion that masturbation was harmful to health. Boys who could not be trusted to keep their hands to themselves were forced to wear these improving steel underpants.

But the real boom in sales has come in the last fifty years, as ‘adult’ shops take advantage of the thriving bondage market.

There are more chastity belts around today than there ever were in the Middle Ages. Paradoxically, they exist to stimulate sex, not to prevent it.

There wasn’t one. It was made up by the papers.

The story of the ‘pharaoh’s curse’ striking down all those who entered Tutankhamun’s tomb when it was discovered by Howard Carter in 1922, was the work of the Cairo correspondent of the

Daily Express

(later repeated by the

Daily Mail

and the

New York Times

).

The article reported an inscription that stated: ‘They who enter this sacred tomb shall swiftly be visited by wings of death.’

There is no such inscription. The nearest equivalent appears over a shrine dedicated to the god Anubis and reads: ‘It is I who hinder the sand from choking the secret chamber. I am for the protection of the deceased.’

In the run-up to Carter’s expedition, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle – who also famously believed in fairies – had already planted the seeds of ‘a terrible curse’ in the minds of the press. When Carter’s patron, Lord Caernavon, died from a septic mosquito bite a few weeks after the tomb was opened, Marie Corelli, writer of sensational best-sellers and the Dan Brown of her day, claimed she had warned him what would happen if he broke the seal.

In fact, both were echoing a superstition that was less than a hundred years old, established by a young English novelist called Jane Loudon Webb. Her hugely popular novel

The Mummy

(1828) single-handedly invented the idea of a cursed tomb with a mummy returning to life to avenge its desecrators.

This theme found its way into all sorts of subsequent tales – even Louisa May Alcott, author of

Little Women

, wrote a ‘mummy’ story – but its big break came with the advent of ‘Tutankhamun-fever’.

No curse has ever been found in an ancient Egyptian tomb.

Of the alleged twenty-six deaths caused by Tutankhamun’s ‘curse’, thorough research published in the

British Medical

Journal

in 2002 has shown that only six died within the first decade of its opening and Howard Carter, surely the number one target, lived for another seventeen years.

But the story just won’t go away. As late as 1970, when the exhibition of artefacts from the tomb toured the West, a policeman guarding it in San Francisco complained of a mild stroke brought on by the ‘mummy’s curse’.

In 2005, a CAT scan of Tutankhamun’s mummy showed that the nineteen-year-old was 1.7 m (5 feet 6 inches) and skinny, with a goofy overbite. Rather than being murdered by his brother, it seems he died from an infected knee.

CLIVE

None of these superstitions should be worried about … touch wood.