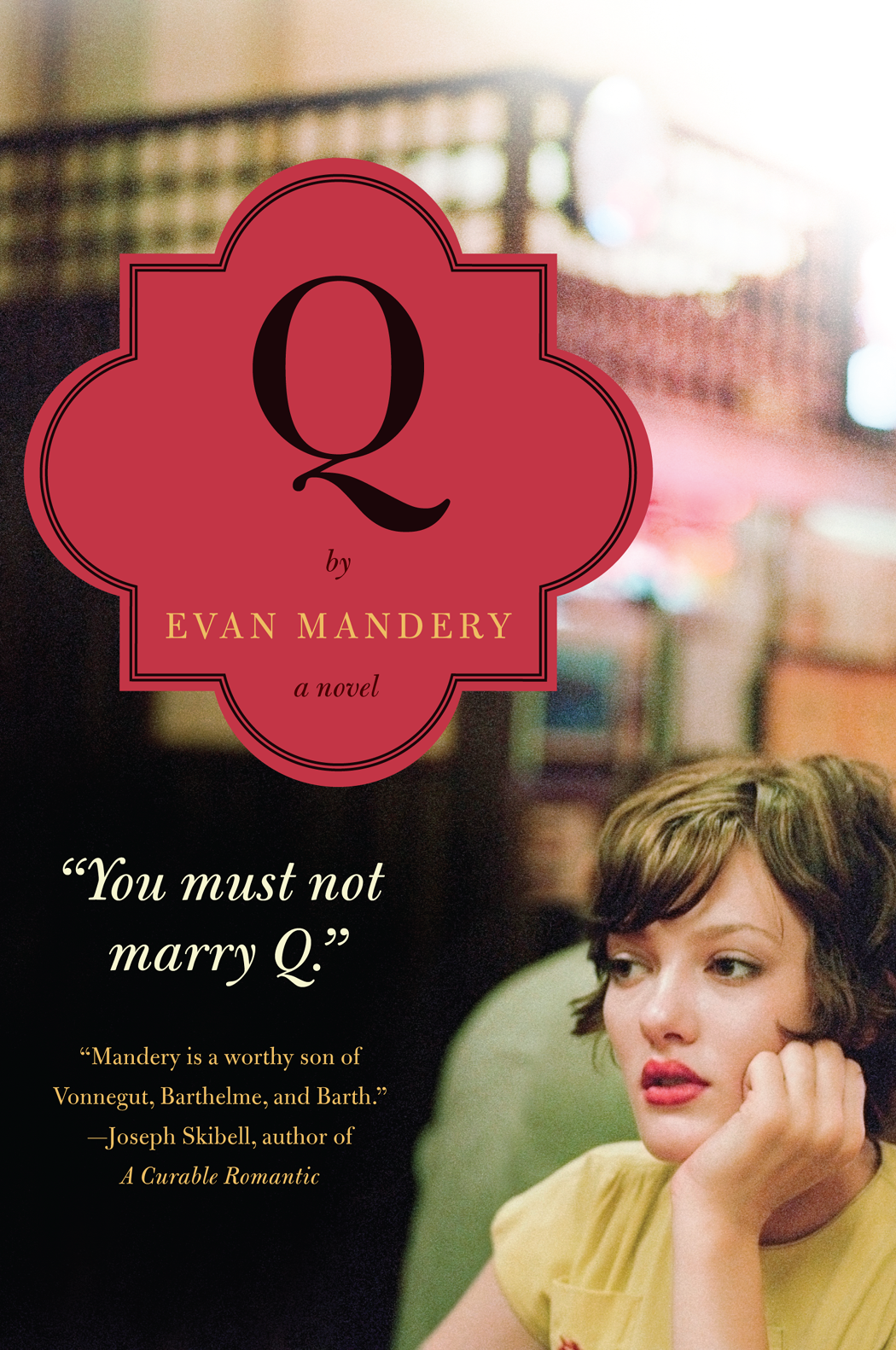

Q: A Novel

Authors: Evan Mandery

Q

A NOVEL

Evan Mandery

For V, my Q

What is the point of this story?

What information pertains?

The thought that life could be better

Is woven indelibly into our hearts and our brains.

PAUL SIMON, “TRAIN IN THE DISTANCE”

Contents

Q

, Quentina Elizabeth Deveril, is the love of my life. We meet for the first time by chance at the movies, a double feature at the Angelika:

Casablanca

and

Play It Again, Sam

. It is ten o’clock on a Monday morning. Only three people are in the theater: Q, me, and a gentleman in the back who is noisily indulging himself. This would be disturbing but understandable if it were to Ingrid Bergman, but it is during

Play It Again, Sam

and he repeatedly mutters, “Oh, Grover.” I am repulsed but in larger measure confused, as is Q. This is what brings us together. She looks back at the man several times, and in so doing our eyes meet. She suppresses an infectious giggle, which gets me, and I, like she, spend the second half of the movie fending off hysterics. We are bonded. After the film, we chat in the lobby like old friends.

“What was that?” she asks.

“I don’t know,” I say. “Did he mean Grover from

Sesame Street

?”

“Are there even any other Grovers?”

“There’s Grover Cleveland.”

“Was he attractive?”

“I don’t think so.”

“Was anybody in the 1890s attractive?”

“I don’t know. I don’t think so.”

“It serves me right for coming to a movie on a Monday morning,” Q says. Then she thinks about the full implication of this reflection and looks at me suspiciously. “What about you? Do you just hang out in movie theaters with jossers all day or do you have a job?”

“I am gainfully employed. I am a professor and a writer,” I explain. “I am working on a novel right now. Usually I write in the mornings. But I can never sleep on Sunday nights, so I always end up being tired and blocked on Monday mornings. Sometimes I come here to kill time.”

Q explains that she cannot sleep on Sunday nights either. This becomes the first of many, many things we learn that we have in common.

“I’m Q,” she says, extending her hand—her long, angular, seductive hand.

“Your parents must have been quite parsimonious.”

She laughs. “I am formally Quentina Elizabeth Deveril, but everyone calls me Q.”

“Then I shall call you Q.”

“It should be easy for you to remember, even in your tired state.”

“The funny thing is, this inability to sleep on Sunday nights is entirely vestigial. Back in graduate school, when I was trying to finish my dissertation while teaching three classes at the same time, I never knew how I could get through a week. That would get me nervous, so it was understandable that I couldn’t sleep. But now I set my own schedule. I write whenever I want, and I am only teaching one class this semester, which meets on Thursdays. I have no pressure on me to speak of, and even still I cannot sleep on Sunday nights.”

“Perhaps it is something universal about Mondays, because the same thing is true for me too. I have nothing to make me nervous about the week. I love my job, and furthermore, I have Mondays off.”

“Maybe it is just ingrained in us when we’re kids,” I say.

“Or maybe there are tiny tears in the fabric of the universe that rupture on Sunday evenings and the weight of time and existence presses down on the head of every sleeping boy and girl. And then these benevolent creatures, which resemble tiny kangaroos, like the ones from that island off the coast of Australia, work diligently overnight to repair the ruptures, and in the morning everything is okay.”

“You mean like wallabies?”

“Like wallabies, only smaller and a million times better.”

I nod.

“You have quite an imagination. What do you do?”

“Mostly I dream. But on the weekends,” she adds, with the faintest hint of mischief, “I work at the organic farm stand in Union Square.”

On the following Saturday,

I visit the farmer’s market in Union Square. It is one of those top ten days of the year: no humidity, cloud-free, sunshine streaming—the sort that graces New York only in April and October. It seems as if the entire city is groggily waking at once from its hibernation and is gathering here, at the sprawling souk, to greet the spring. It takes some time to find Q.

Finally, I spot her stand. It is nestled between the entrance to the Lexington Avenue subway and a small merry-go-round. Q is selling a loaf of organic banana bread to an elderly lady. She makes me wait while the woman pays her.

Q is in a playful mood.

“Can I help you, sir?”

“Yes,” I say, clearing my throat to sound official. “I should like to purchase some pears. I understand that yours are the most succulent and delicious in the district.”

“Indeed they are, sir. What kind would you like?”

At this point I drop the façade, and in my normal street voice say, “I didn’t know there was more than one kind of pear.”

“Are you serious?”

“Please don’t make fun of me.”

Q restrains herself, as she did in the theater, but I can see that she is amused by my ignorance. It is surely embarrassing. I know that there are many kinds of apples, but somehow it has not occurred to me that pears are similarly diversified. The only ones I have ever eaten were canned in syrup, for dessert at my Nana Be’s house. To the extent that I ever considered the issue, I thought pears were pears in the same way that pork is pork. Q thus has every right to laugh. She does not, though. Instead she takes me by the hand and leads me closer to the fruit stand.

This is infinitely better.

“We have Bartlett, Anjou, Bosc, and Bradford pears. Also Asian pears, Chinese whites, and Siberians. What is your pleasure?”

“I’ll take the Bosc,” I say. “I have always admired their persistence against Spanish oppressors and the fierce individuality of their language and people.”

“Those are the Basques,” says Q. “These are the Bosc.”

“Well, then, I’ll take whatever is the juiciest and most succulent.”

“That would be the Anjou.”

“Then the Anjou I shall have.”

“How many?”

“Three,” I say.

Q puts the three pears in a bag, thanks me for my purchase, and with a warm smile turns to help the next customer. I am uncertain about the proper next step, but only briefly. When I return home and open the bag, I see that in addition to the pears Q has included a card with her phone number.

On our first date

we rent rowboats in Central Park.

It is mostly a blur.

We begin chatting, and soon enough the afternoon melts into the evening and the evening to morning. We do not kiss or touch. It is all conversation.

We make lists. Greatest Game-Show Hosts of All Time. She picks Alex Trebek, an estimable choice, but too safe for her in my view. I advance the often-overlooked Bert Convy. We find common ground in Chuck Woolery.

Best Sit-Com Theme Songs. I propose

Mister Ed

, which she validates as worthy, but puts forward

Maude

, which I cannot help but agree is superior. I tell her the little-known fact that there were three theme songs to

Alice

, and she is impressed that I know the lyrics to each of them, as well as the complete biography of Vic Tabak.

We make eerie connections. During the discussion of Top Frozen Dinners, I fear she will say Salisbury steak or some other Swanson TV dinner, but no, she says Stouffer’s macaroni and cheese and I exclaim “Me too!” and tell her that when my parents went out on Saturday nights, I would bake a Stouffer’s tray in the toaster oven, brown bread crumbs on top, and enjoy the macaroni and cheese while watching a

Love Boat–Fantasy Island

doubleheader, hoping Barbi Benton would appear as a special guest. We discover that we favor the same knish (the Gabila), the same pizza (Patsy’s, but only the original one up in East Harlem, which still fires its ovens with coal), the same Roald Dahl children’s books (especially

James and the Giant Peach

). We both think the best place to watch the sun set over the city is from the bluffs of Fort Tryon Park, overlooking the Cloisters, both think H&H bagels are better than Tal’s, both think that Times Square had more character with the prostitutes. One after the other: the same, the same, the same. We sing together a euphonic and euphoric chorus of agreement, our voices and spirits rising higher and higher, until, inevitably, we discuss the greatest vice president of all time and exclaim in gleeful, climactic unison “Al Gore! Al Gore! Al Gore!”

It is magical.

I escort Q home to her apartment at Allen and Rivington in the Lower East Side, buy her flowers from a street vendor, and happily accept a good-night kiss on the cheek. Then I glide home, six miles to my apartment on Riverside Drive, feet never touching the ground, dizzy. Already I am completely full of her.

For our second date

I suggest miniature golf. Q agrees and proposes an overlooked course that sits on the shore of the Hudson River. The establishment is troubled. It has transferred ownership four times in the last three years, and in each instance gone under. Recently it has been redesigned yet again and is being operated on a not-for-profit basis by the Neo-Marxist Society of Lower Manhattan, itself struggling. The membership rolls of the NMSLM have been dwindling over the past twenty years. Q explains that the new board of directors thinks the miniature golf course can help refill the organization’s depleted coffers and will be just the thing to make communism seem relevant to the youth of New York. They are also considering producing a rap album, tentatively titled, “Red and Not Dead.”

Q is enthusiastic about the proposed date and claims on our walk along Houston Street to be an accomplished miniature golfer. I am skeptical. When we arrive at the course, I am saddened to see that though it is another beautiful spring Saturday in the city, the course is almost empty. I don’t care one way or the other about the Neo-Marxist Society of Lower Manhattan, but I am a great friend of the game of miniature golf. The good news is that Q and I are able to walk right up to the starter’s booth. It is attended by an overstuffed man with a graying communist mustache who is reading a newspaper. He is wearing a T-shirt that has been machine-washed to translucence and reads:

Che

Now More Than Ever

The sign above the starter’s booth has been partially painted over, ineptly, so it is possible to see that it once said:

Green Fee:

$10 per player

The second line has been whited out and re-lettered, so that the sign now says:

Green Fee:

Based on ability to pay

I hand the starter twenty dollars and receive two putters and two red balls.

“Sorry,” I say. “These balls are both red.”

“They’re all red,” he says.

“How do you tell them apart?” I ask, but it is no use. He has already returned to his copy of the

Daily Leader

.

The first hole is a hammer and sickle, requiring an accurate stroke up the median of the mallet, and true to her word, Q is adept with the short stick. She finds the gap between two wooden blocks, which threaten to divert errant shots into the desolate territories of the sickle, and makes herself an easy deuce. I match her with a competent but uninspired par.

The second hole is a Scylla-and-Charybdis design, a carryover from the original course, which has rather uncomfortably been squeezed into the communist motif. One route to the hole is through a narrow loop de loop, putatively in the shape of Stalin’s tongue; the other requires a precise shot up and over a steep ramp—balls struck too meekly will be redeposited at the feet of the player; balls struck too boldly will sail past the hole and land, with a one-stroke penalty, in a murky pond bearing the macabre label “Lenin’s Bladder.” Undaunted, Q takes the daring route over the ramp and nearly holes her putt. On the sixth, the windmill hole, she times it perfectly, her ball rolling through at the precise moment Trotsky’s legs spread akimbo, and finds the cup for an ace. Q squeals in glee.

Q’s play inspires my own. On the tenth, I make my own hole in one, a double banker around Castro’s beard, and the game is on. On the fourteenth, I draw even in the match, with an improbable hole out through a chute in the mouth of Eugene V. Debs. Q responds by nailing a birdie into Engels’s left eye. We come to the seventeenth hole, a double-decker of Chinese communists, dead even. The hole demands a precise tee shot between miniature statutes of Deng Xiaopeng and Lin Biao in order to find a direct chute to the lower deck. Fail to find this tunnel to the lower level and the golfer’s ball falls down the side of a ramp and is deposited in a cul-de-sac, guarded by the brooding presence of Jiang Qing, whose relief stares accusatorily at the giant replica of Mao, which presides over all action at the penultimate hole.

Q capably caroms her ball off Deng, holes out on the lower deck for her two, and watches anxiously as I take my turn. I strike my putt slightly off center and for a moment it appears as if the ball will not reach Deng and Lin—but it does, and hangs tantalizingly on the edge of the chute. Q is breathless, as am I, until the ball falls finally and makes its clattering way to the lower level. Unlike Q’s ball, however, mine does not merely tumble onto the lower level in strategic position; it continues forward and climactically drops into the cup for a magnificent ace and definitive control of the match. I walk down the Staircase of One Thousand Golfing Heroes, grinning all the while, and bend over to triumphantly collect my ball from the hole. Then I rise and hit my head squarely on Mao’s bronzed groin.

This experience is painful (quite) and disappointing (we never get to play the eighteenth hole and thus miss our chance to win a free game by hitting the ball into Kropotkin’s nose), but not without its charms: Q takes me home in a cab, tucks me into bed, and kisses me on the head. This makes all the pain miraculously disappear.

The next day,

Q calls to check on me.

On the phone, she tells me that date number three will be special. This is apparent when she collects me at my apartment. When I answer the door, she is wearing a simple sundress with a white carnation pinned into her shining hair, a mixture of red and brown. She looks like a hippie girl, though no hippie ever looked quite like this. She is radiant.