Prisoners of the North (42 page)

Read Prisoners of the North Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Harper of Heaven

was published in 1948 after the Service family returned to France and eventually exchanged Nice for Monte Carlo. (In Brittany, their winter residence, Dream Haven, had to undergo extensive repairs as a result of the German occupation.) Service’s second volume of autobiography is a rambling piece of work, as much a travelogue as a memoir. Subtitled

A Record of Radiant Living

, it covers his career following the Yukon period. But by the time it appeared, “the old codger,” as he called himself, was approaching seventy-five and giving some thought to the hereafter, as the quatrain on the book’s title page suggests:

Although my sum of years may be

Nigh seventy and seven,

With eyes of ecstasy I see

And hear the Harps of Heaven

With worldwide reviews that ranged from “a tough, violent book”

(London Daily Herald)

to “this gem of a book”

(Seattle Post-Intelligencer)

, one might have expected Service, with sixteen bestsellers to his credit, to take life easy after a long and successful career and spend his declining years lazing about as he always insisted he wished to do. On the contrary, he plunged into a veritable orgy of creation. Between 1949 and 1958 he published nine original books of verse with the alliterative titles that had become his trademark, such as

Songs of a Sun-Lover, Rhymes of a Roughneck, Lyrics of a Lowbrow, Carols of an Old Codger

. He also published

More Collected Verse

and

Later Collected Verse

and a new edition of

Why Not Grow Young

.

For all that period, Service wrote a verse a day while still indulging in his three-hour walks every afternoon. He didn’t need to write for money. The royalties kept coming. It was as if Service had taken a new lease of life and was writing as much for himself as for his dwindling audience. “The writing racket is not what it used to be,” he remarked at the time, “but this old codger still sells.” James Mackay has noted, “… it is ironic, that much of his best work, truly sublime poetry, should come at a time when Robert was no longer fashionable.”

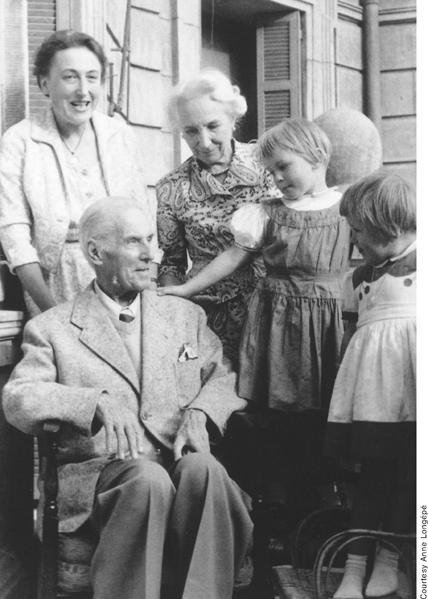

The poet in his final years surrounded by family and friends

.

When I interviewed him in Monte Carlo in 1958 he was well past his eightieth year, having published at least one thousand poems with perhaps as many unpublished. I was appearing on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s Sunday night flagship program

Close-Up

at the time and was assigned to visit him in Monaco to prepare a half-hour television interview. There was some difficulty in clearing the assignment since several members of the corporation’s upper echelon kept insisting that Service was dead. However, a letter from the poet himself cleared that up: “For me this will probably be a unique television show as I am now crowding eighty-five and the ancient carcass will soon cease to function. For that reason I hope you will bring it off successfully. My home here makes a nice setting for an interview, which if well planned could be quite attractive.”

Patrick Watson, my producer, and I arrived with a television crew in May. The poet met us at the door of his Villa Aurore, overlooking the warm Mediterranean, and introduced us to his wife, Germaine. He was casually dressed in a sleeveless sweater and slacks—a small, birdlike man with brightly veined cheeks, a sharp nose, and a mild, Scottish accent. We had started to discuss the interview when Service held up his hand.

“It’s all arranged,” he said. “I spent the week working it up. Here’s your script. I’m afraid you’ve got the smaller part because, you see, this is

my

show!” He handed me two sheets of paper, stapled and folded. “It’s in two parts,” he said. “We can do the first after lunch. Now you boys go back to your hotel and you [to me] learn your lines. I already know mine, letter perfect. Come back this afternoon and we’ll do it.”

I looked at Watson. This is not the way spontaneous television interviews are conducted. He gave a kind of helpless shrug and we left.

“What do we do now?” I asked.

“I guess we’d better read what he’s written,” Watson said.

What Service had written, it turned out, was pretty good—lively, witty, self-effacing, romantic: “I’m eighty-five now and I guess this will be my last show on the screen. Oh, I’m feeling fine though I’m a bit of a cardiac. In middle age I strained my heart trying to walk on my hands. After sixty a man shouldn’t try to be an athlete. Only yesterday I was talking politics to a chap on the street. I’m ‘Right’ and he was ‘Left’ so we got to shouting, when suddenly I felt the old ticker conk on me, and I had to go home in a taxi, chewing white pills. Say, wouldn’t it be a sensation if I croaked in the middle of this interview?”

When we returned, Service was easily persuaded to submit to an unscripted interview. But whenever one of my questions coincided with one in the script, he gave me a word-perfect answer, and that included the line about croaking on television. Service, the old actor, even managed to make that sound spontaneous.

In between set-ups, the poet and I talked about the Yukon. He remembered my mother very well and talked about Lousetown, the tenderloin district across the Klondike River. “We used to go down the line every Saturday night,” he said, employing a euphemistic colloquialism that was still part of the jargon in my mining-camp days.

In the interview that was spread over three days we went over some of the highlights of his career, including the intervention of the bank inspector who had first sent him to the Yukon and so changed his life. “He was the God in my machine,” said Service. “I often wished I had thanked him before he died.” We talked about his various adventures such as his days with the Turkish Red Crescent, when he worked in the cholera camp at San Stefano. “I couldn’t stick it any longer. I deserted, really,” Service admitted. He told of his time in the Paris slums. “I went with the police gang and they took me all through every part of Paris that was disreputable,” he said, thus disputing the stories in his own autobiography. “I got to know that side, the seamy side of Paris, better than any writer of the time knew it,” he said, a little proudly.

And we talked about “The Shooting of Dan McGrew,” which he insisted he loathed. “It’s not exactly what I would call tripe, but there’s no poetry—no real poetry to it to my mind,” he said, and added, “I don’t write poetry anyway so there’s no use talking like that. Here I am—crucified on the cross of Dan McGrew. There you are.”

The author interviewing Service at his Monaco home in the spring of 1958 for the CBC’s flagship program

, Close-up.

The poet died three months later

.

Yet when the time came to recite for television his best-known work, he showed an eagerness that belied his own critique. “I’m looking forward to it,” he said when we arrived on the third morning to get his verse and his voice on film. He was in great fettle and his eyes were bright as he began, “A bunch of the boys were whooping it up …”

When the filming was complete, Service with great ceremony opened a bottle of champagne that he had put aside for the occasion. All during the filming he had been an enthusiastic interview subject, lively and ebullient.

“It’s made me young again,” he said. “I’m just living it.” Now, as we toasted him, he seemed cast down.

“Is it really over?” he said. “Haven’t you got any more questions? I could go on, you know.” But the crew was already packing up the equipment.

“Oh, I do wish we could go on,” said Service. “I wish it didn’t have to stop.” He stood in his dressing gown in the doorway of his villa, and the wind catching the silver of his hair and blowing it over his face gave him an oddly dishevelled look.

“I wish it could go on forever,” said Robert Service, and I caught, briefly, the memory of the telegraph operator, running along the riverbank, pleading with us to stay just a little longer.

The interview was shown in June and was a great success. The scene that caught everyone’s fancy was Service’s “spontaneous” remark about croaking in front of the cameras. It was indeed his last performance. That September in his Dream Haven in Brittany, his heart finally did give out, and the bard of the Yukon was buried under the sun he loved so well and far, far from that lovely but chilly domain that in capturing him would give him fame and fortune.

Afterword

The five disparate characters who make up this chronicle—a builder, an explorer, a titled lady, an eccentric, and a poet—are unique. At first glance they seem to have had little in common save for their links with the North. On closer inspection, however, we can see that they shared certain traits that made them exceptional. They were all rugged individualists—impatient of authority, restless, energetic, and ambitious. They were secure within themselves—and driven by a romantic wanderlust that freed them from the run-of-the-mill existence on which they so often turned their backs.

They belong to an era when the going was tough and travel was a challenge and sometimes a hardship. Joe Boyle, arriving at Carmack’s Post on the Yukon and finding himself among a group of stranded tenderfeet, goaded these incompetents by threatening and cajoling to work their way on foot with him through the mountains in the worst possible weather to the nearest seaport. They gave him a gold watch for that.

Vilhjalmur Stefansson spent his Arctic career trotting for thousands of miles behind a dog team, rarely taking his ease on the sledge.

Lady Franklin never encountered a mountain she didn’t want to climb and thought nothing of crossing Van Diemen’s Land on foot on a journey that had killed those who came before.

John Hornby made a fetish of his ruggedness, doing everything the hard way, trudging for fifty miles through a Barrens blizzard and boasting about it.

Robert Service, who survived the Rat River trail, made a habit of working out every afternoon until his doctors slowed him down.

They lived by their own rules, these five—flouting authority, contemptuous of regulations, confident of their own instincts and abilities. Boyle played catch-me-if-you-can with the military and political authorities who tried vainly to hem him in. Stefansson resisted all efforts to pull him out of the Arctic and instead of going south, as ordered, headed farther into the North. Jane Franklin had her own ideas about her husband’s fate and when these were ignored took on the job of searching for him herself. Hornby was a wild card who exulted in his role and died tragically, rejecting sensible advice, while Service shunned the dictates of society and went his own way, a loner to the end.

They were all loners. Did any of them have the kind of intimate friend to whom one can pour out one’s heart? There is little evidence of that in their varied sagas. In all too brief moments Boyle enjoyed a relationship of sorts with Queen Marie, and also, perhaps, was at ease with his old friend Teddy Bredenberg in his dying months, but there is little indication of any traditional understanding. Like the others, he was not a family man. He was quite prepared to run off to sea with scarcely a word to his kin, nor was either of the marriages into which he plunged successful. The two offspring he did not abandon were in awe of him, but their relationship cannot be described as close.

Stefansson enjoyed several lengthy affairs, but he scarcely mentioned the novelist Fannie Hurst, who was his mistress for seventeen years. He refused to recognize his son, Alex, the product of his liaison with the capable Inuit widow Pannigabluk. His four-year romance with Betty Brainerd faded after he ignored her letters to him. It is clear that he put his work and his ambitions first; his various relationships came close to being afterthoughts. Only after he had done with exploring did he take the time and trouble to marry. He rejected outward intimacies. They were, as his friend Richard Finnie remarked, out of keeping with his image as a rough, independent explorer. He would have recoiled had he heard his wife remark publicly, as she did after his death, that she had enjoyed the best sex of her life with him.