Prime Time (31 page)

Authors: Jane Fonda

Tags: #Aging, #Gerontology, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses - United States, #Social Science, #Rejuvenation, #Aging - Prevention, #Aging - Psychological Aspects, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Jane - Health, #Self-Help, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Growth, #Fonda

Reverend Bill Stayton and his bride, Kathy.

“Tell me about your relationship,” I prompted.

“Well, first of all, I fell in love the minute I saw her,” Bill answered with relish. “It was at freshman orientation; I was a sophomore and Kathy was a freshman. I was entertaining at a church youth group at the school and I saw her. It took several weeks to find out who she was so I could ask her out.”

After their first date, Bill said, “I wrote my parents and said, ‘I have met the person.’ ”

“How long did it take you to fall in love with Bill, Kathy?”

“Oh, gosh. Six months?” They both laughed.

“She went home to meet my parents at Christmas,” Bill recalled. “Then we got engaged in February and married in September of the next year. So, we knew each other just a year. We often say we got married to have sex.” They had both been virgins.

Kathy added, “That’s not really the right reason.… You know, though, it worked out for us.”

The Long Haul

I wanted to know what they credited their longevity as a couple to. “Fifty-five years!” I exclaimed, “It’s hard to find one person who is not only good for the early, family-building stage but is still good in the post-children stage.”

“I always knew, right from the beginning,” Kathy said, “that people didn’t expect young people’s marriages to last. So I was determined I wasn’t going to be like what people expected.”

“We had some tears in there, and conflicts,” Bill interjected, wanting me to know that it hadn’t all been an easy run.

“Yes,” said Kathy, “but we knew our love for each other was strong, even though, at times, we may not have liked each other. When we had differences I could always say to myself, ‘This too shall pass,’ and not worry that our love was threatened. Besides, we have shared values, we enjoy the same types of entertainment—theater, classical music, art museums, film—and we’ve never harbored jealousy of the friends of the opposite sex each of us have.”

Bill smiled at his wife. “I have never, ever thought of separation or divorce. It has never been a part of me.” He added that one hard time “was during the feminist period where Kathy felt she had been with her parents and then with me and she had never been her own person.”

“I went from one dependency to another,” Kathy explained. “At first, when Bill was in seminary, I worked—we both worked. That was survival. But after the first child, I did not work for a number of years. Or, rather, I should say I didn’t get paid for a number of years.”

“Ah yes,” I interjected. “Unpaid labor? You mean you became a homemaker?”

“You got it! But in the seventies, when Bill began his postdoctoral work and his career at the University of Pennsylvania, I went back to work as an administrative assistant and a middle school music teacher. Yet my responsibilities at home didn’t lessen. We were not in a financial position to hire housekeeping or landscaping help, and I was the one who negotiated help from our children. I made a decent salary to help pay for one of our kids to go to college. But it got swept up into other expenses of our household.

“Probably,” Kathy continued, “our biggest clash of value has been over how to spend money. Because I’ve always grown up with the belief that ‘where your money is, that’s where your heart is.’ And my heart was in a different place than Bill’s heart. But as a woman of my generation, I fell into the ‘dependent’ role of the wife, wanting to please my spouse, not believing that my voice, if in opposition to Bill’s, particularly around issues of large financial expenditures, was equal to his, and I would give in to his desires around those matters and then harbor resentment. Not smart!”

Bill then told me that they had considered separating for a year, to give Kathy a sense of independence, as a way of strengthening both her and their marriage. When that was too complicated because of the children, their therapist suggested that they work on separateness in their own home, by having separate financial accounts.

Bill recalled, “And so for a year—and this was so painful for me—you bought your own Christmas presents for the children and I bought my Christmas presents for the children. Before that everything had always been from Mom and Dad—even though she bought the presents,” he told me. “And for a year she decided not to go to church anymore. I would go on Sundays and people would say, ‘Where’s Kathy?’ ”

Kathy frowned. “I don’t remember that it was for a whole year.”

Achieving Individuation

“When did this begin,” I asked Kathy, “this feeling that you needed to stand on your own two feet?”

“In the early seventies, when we lived in Pennsylvania, I resonated with the words that Gloria Steinem was saying. I just said, ‘That’s true! She speaks for me.’ ”

“Do you remember what it was she said that so resonated with you?” I asked.

“It had to do with roles. When you are feeling imprisoned by what is expected of women, when you don’t feel the expectations suit you.”

“Because you didn’t feel you could be a full person within those expectations?”

“Yes. You feel like, ‘Is this what I should be doing?’ That kind of stuff.”

Privately, I asked Kathy if Bill had been threatened by all this change.

“Yes,” she said. “I think the whole feminist movement has had an impact on all the men as well as women, and I think at that time, in his head, Bill was a feminist, but in actions it was life as usual.”

“I was that way myself for a few years,” I admitted. “A theoretical feminist but not an embodied one.”

Bill and Kathy Stayton.

TIM SCOTT, SPENCER STUDIOS

“It’s hard to unlearn those things,” Kathy mused. “I didn’t really get into feminism a lot. I was kind of on the periphery but watching to see what was out there. I have more courage in my head maybe than in my body at times.”

“Perhaps, but you did go out and begin to create your own space, right?”

“Well, actually, I always have used my leadership skills throughout my life, even while being a full-time homemaker. But I did move into new territory—in terms of my own ‘space’—in the early seventies.”

Finding Identity in Community

“It was around that time that I started doing community things that Bill didn’t do and we just had different lives,” Kathy recalled. “One of those things was the symphony orchestra. I played the violin, and when I was part of the orchestra no one asked, ‘What does your husband do?’ You really are your own person. You just learn your part and are a part of the group. And rehearsals were every week, so Bill had to take the kids. I wasn’t going to give it up. And that really did help even before I was aware that that’s what it was doing for me.

“Also, in the early nineties,” she said, “the board of our denomination, the American Baptist Churches of the USA, issued a new policy, a one-sentence resolution that caught us all by surprise: ‘The practice of homosexuality is incompatible with Christian teaching.’ Period. Our church was up in arms about this and we began our activism and, within a year, we had a lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgendered (LGBT) allied group within the church. That was where I became very involved. It was not hard to do because, with Bill being in the field of sexuality, we already knew people who were transgender, transsexual, gay, lesbian, cross-dressers, the whole spectrum of human expressions in sex and gender.” Kathy talked about the process they had to go through before their congregation finally agreed to become a member of the Association of Welcoming and Affirming Baptists.

Kathy explained that the work she and so many others have done for decades now on LGBT issues has blossomed. “I have a network of people I know all through Philadelphia, and they are very meaningful to me,” she said. “Some are clergy, some are lay; they are all out, in their churches and, I presume, in their jobs, but who knows? They became really my second church because what was important about our church was not necessarily the theology or anything; it was the community of people who will support us even though they may not be active in our group. They will support us, and then they talk about it. In fact, some people said they went back to their retirement communities and they would talk about these issues at their dinner table and it kind of grew.”

Having found her own voice, her own way to make a difference, Kathy now works within her new church community in Atlanta, on the board of directors for the Association of Welcoming and Affirming Baptists and the Marriage Equality team, which is a group that advocates for marriage equality for same-sex marriage in Atlanta. “We will start up in Atlanta—we’ll see if we can ever get the state of Georgia,” she told me with a smile.

But Kathy didn’t end the discussion there. She wanted me to understand another part of why their marriage has survived for so long, in addition to her finding her own space. “We have always been a part of a community of people who are supportive,” she said, “and that has happened in the churches we have been in, with people who have lived a long time and seemed to be happy in their old age and they were still active—and so, you know, we had role models.”

“So, there was a community rooting for you and dependent on the two of you to stay together as a couple?”

“Well, I don’t know if they depended on us, but it was my expectation that we would stay together, I think. I would have let myself down.”

I have thought a lot about these words of Kathy’s, this thing about what’s expected out of marriage, what we expect from ourselves. It saddens me that we just don’t have these same expectations anymore. Quite the contrary. The expectation these days is that one

won’t

stay together, and so when the going gets rough, many tend to move on. And yet … maybe that is becoming inevitable in the face of our newly gained longevity and our desire for 360-degree relationships, intimate and passionate all the way. Margaret Mead felt that every woman needed three husbands: one for the youthful sexy stage, one for bringing security to the family-building stage, and one for Third Act companionship.

Right now, looking back at the beginnings and endings of my own relational scenarios, I feel that if our loves must be segmented into more doable phases, what becomes critical is to take the time and make the effort to learn the lessons each phase offers so that at least we deepen and grow in our ability to be a loving, intimate partner. Who was it who said, “If you keep doing the same things the same way, you keep getting the same results”?

Intentionality

“I think one of the things that has really been important for us,” Bill remarked, “and we had to become intentional about this, was spending time for just us. I’ve learned a lot working with people, and one of the things that happens all too often is that when people get married you spend all your time on maintenance: the kids, fixing up the home, doing the work around the house. Whereas when people start getting together, you’re nurturing the relationship. Then they get married and all that nurturance tends to turn over into maintenance, and when I work with couples it’s putting play back into their relationship. Just going to do something with the kids is not nurturance of the relationship. It might be nurturance of the family, but it is also maintenance.”

“So, when does this start to happen between couples?” I asked.

“Kathy and I became intentional when our kids were becoming teenagers. We set time aside just to be together because kids take up all your time at home. So, we became really intentional. Like we set ten o’clock at night, something like that—the kids couldn’t break in on us. It was time when we could talk about planning a party, or we could—”

“Have sex?” I queried.

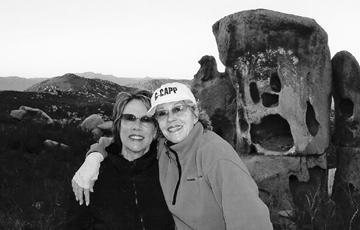

With Jewelle Bickford on a hike at Rancho La Puerta in 2008.

“Oh yeah. We’ve always had a good sex life.”

“I think that is the glue,” I interjected. “Isn’t it the thing that helps in the forgiveness, in smoothing over the rough passages?”

“Yeah, absolutely,” Bill replied.