Prime Time (2 page)

Authors: Jane Fonda

Tags: #Aging, #Gerontology, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses - United States, #Social Science, #Rejuvenation, #Aging - Prevention, #Aging - Psychological Aspects, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Jane - Health, #Self-Help, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Growth, #Fonda

Except that we don’t have the sheet music to this new symphony. We—today’s boomers and seniors—are the pioneer generations, the ones who need to compose together a template for how to maximize the potential of this amazing gift of time, so as to become whole, fully realized people over the longer life arc.

In attempting to chart a course for myself into my sixties and beyond, I’ve found it helpful to view the symphony of my own life in three acts, or three major developmental stages: Act I, the first three decades; Act II, the middle three decades; and Act III, the final three decades (or however many more years one is granted).

As I searched for ways to understand the new realities of aging, I discovered the arch and the staircase.

The Arch and the Staircase

Here you see two diagrams that I have had drawn, because they make visualizable two conceptions of human life that have come to mean a lot to me.

One diagram, the arch, represents a biological concept, taking us from childhood to a middle peak of maturity, followed by a decline into infirmity.

The other, a staircase, shows our potential for upward progression toward wisdom, spiritual growth, learning—toward, in other words, consciousness and soul.

The vision behind these diagrams was developed by Rudolf Arnheim, the late professor emeritus of the psychology of art at Harvard University, and for me they are clear metaphors for ways we can choose to view aging. Our youth-obsessed culture encourages us to focus on the arch—age as physical decline—more than on the stairway—age as potential for continued development and ascent. But it is the stairway that points to late life’s promise, even in the face of physical decline. Perhaps it should be a spiral staircase! Because the wisdom, balance, reflection, and compassion that this upward movement represents don’t just come to us in one linear ascension; they circle around us, beckoning us to keep climbing, to keep looking both back and ahead.

Rehearsing the Future

Throughout my life, whenever I was confronted by something I feared, I tried to make it my best friend, stare it in the face, and get to know its ins and outs. Eleanor Roosevelt once said, “You gain strength, courage, and confidence by every experience in which you really stop to look fear in the face.” I have found this to be true. This is how I discovered that knowledge about what lies ahead can empower me, help me conquer my fears, take the wind out of the sails of my anxiety. Know thine enemy! Remember Rumpelstiltskin, the evil dwarf in the Grimms’ fairy tale? He was destroyed once the miller’s daughter learned his name and called it out. When we name our fears, bring them out into the open, and examine them in the light, they weaken and wither.

So, one of the ways I have tried to overcome my fears of aging involved rehearsing for it. In fact, I started doing this in Act II. I believe that this rehearsal for the future (along with doing a life review of the past) is part of why I have been able—so far—to live Act III with relative equanimity.

Being with my father when he was in his late seventies and in decline due to heart problems was what began to shatter any childhood illusions I’d had of immortality. I was in my mid-forties, and it hit me that with him gone, I would be the oldest one left in the family and, before too long, next at the turnstile. I realized then that it was not so much the idea of death itself that frightened me as it was being faced with regrets, the “what if”s and the “if only”s when there is no time left to do anything about them. I didn’t want to arrive at the end of the Third Act and discover too late all that I had not done.

Kissing my father as I brought his Oscar for

On Golden Pond

home to him, because he was too sick to attend the ceremony.

JOHN BRYSON © 2011 BRYSON PHOTO

I began to feel the need to project myself into the future, to visualize who I wanted to be and what regrets I might have that I would need to address before I got too old. I wanted to understand as much as possible what cards age would deal me; what I could realistically expect of myself physically; how much of aging was negotiable; and what I needed to do to intervene on my own behalf with what appeared to be a downward slope.

The birth of my two children had taught me the importance of knowledge and preparation. The first birth had been a terrifying, lonely experience; I went through it unprepared and unrehearsed, swept along passively in a sea of pain. The second birth was quite the opposite. My husband and I worked with a birth educator in the months leading up to my due date, so that I was able to visualize what would happen and know what to do. The physical ordeal was no less grueling, the process no faster, but the experience itself was transformed. With knowledge and rehearsal, I found it easier to ride atop the sequence of events rather than be totally submerged by the pain.

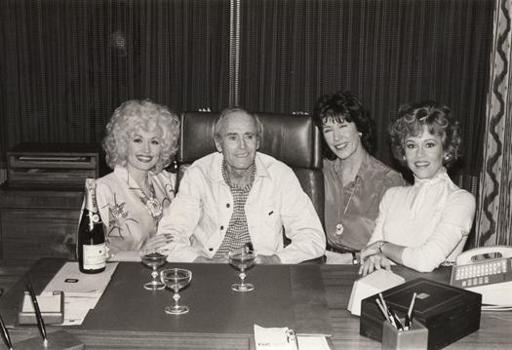

Dad came to visit the

Nine to Five

set

.

I brought what I’d learned from childbirth to my experience facing late midlife. As I said, I was scared back then—it is hard to let go of children, of the success that came with youth, of old identities when new ones aren’t yet clearly defined. I felt I could choose whether to be blindly propelled into later life, in denial with my eyes wide shut, or I could take charge and seek out what I needed to know in order to make informed decisions in the many changing areas of my life. That’s why, in 1984, at age forty-six, before I’d even had my first hot flash, I wrote

Women Coming of Age,

with Mignon McCarthy, about what women can expect, physically, as they age, and what parts of aging are negotiable. It was a way to force myself to confront and rehearse the future. I was shocked to discover how little research had been devoted to women’s health. Most medical studies I found had been done on men. I’m happy to say this has started to change.

At forty-six, I began to envision the old woman I wished to be, and I described her in that book:

I see an old woman walking briskly, out-of-doors, in every season. She’s feisty. She’s not afraid of being alone. Her face is lined and full of life. There’s a ruddy flush to her cheeks and a bright curious look in her eye because she’s still learning. Her husband often walks with her. They laugh a lot. She likes to be with young people and she’s a good listener. Her grandchildren love to tell her stories and to hear hers because she’s got some really good ones that contain sweet, hidden lessons about life. She has a conscious set of values and the knack to make them compelling to her young friends.

This is an example of rehearsing the future … good to do at any age! I’m glad I wrote it down, because it’s fun for me to read my forty-six-year-old vision of my senior self, almost thirty years later, as a reality check to see how well I’m doing. Some days, I actually think I’m doing pretty well. I’m still feisty, and my solitude (which I cherish) doesn’t feel like loneliness. Humor has definitely come to the fore. I’m no longer married, but I do walk together with my—what to call the man I am with when I’m seventy-two and unmarried? “Boyfriend” sounds too juvenile, don’t you think? So then, what? “Lover?” That seems too in-your-face. I think I’ll go with “honey.” Anyway, my honey and I walk together, we laugh a lot, and we try to swing-dance for fifteen or twenty minutes every night—when we can. I feel I may have finally conquered my difficulties with intimacy. (Or maybe I just found a man who isn’t scared of it!)

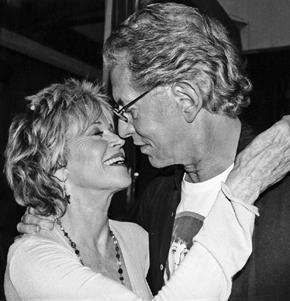

Richard and me in 2009.

MARY VINETTE

MARYVINETTE.COM

Gerontologists such as Bernice Neugarten have learned from their studies of the aged that traumatic events—widowhood, menopause, loss of a job, even imminent death—are not experienced as traumas “if they were anticipated and, in effect,

rehearsed

as part of the life cycle.”

3

Betty Friedan, in her book

The Fountain of Age,

wrote, “The finding emerges that the difference between knowing and planning, and not knowing what to expect (or denial of change because of false expectations) can be the crucial factor between moving on to new growth in the last third of life, or succumbing to stagnation, pathology, and despair.”

With the help of many friends of all ages, as well as gerontologists, sexologists, urologists, biologists, psychologists, experts in cognitive research and health care, and a physicist or two, I have written this book. Even though I was already in my own Act III, doing this has been a form of rehearsal—for myself and for you, the reader. I wanted to be prepared and learn all I could. I wanted to be able to say to myself and to you, “Let’s make the most of the years that take us from midlife to the end, and here’s how!”

I do not want to romanticize the process of aging. Obviously, there is no guarantee that this will be a time of growth and fruition. There are negatives to any stage of life, including potentially serious issues of mental and physical health. I cannot address all these things within the scope of this book. As we know, some of how life unfolds is a matter of luck. Some of it—about one-third, actually—is genetic and beyond our control. The good news is that this means that for a lot of it, maybe two-thirds of the life arc, we

can

do something about how well we do.

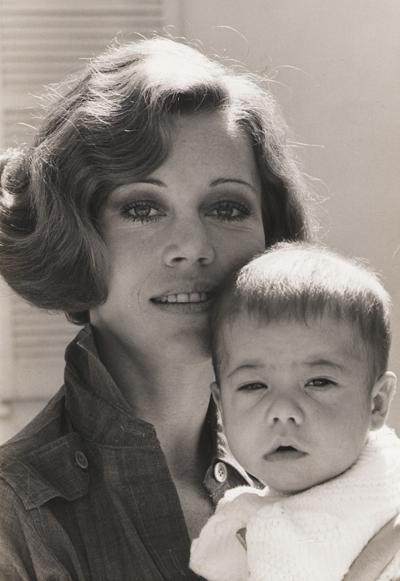

Holding Vanessa during the filming of

They Shoot Horses, Dont’t They?

This book is for those of us who, like me, believe that luck is opportunity meeting preparation; that with preparation and knowledge, with information and reflection, we can try to raise the odds of being lucky, and of making our last three decades—our Third Acts—the most peaceful, generous, loving, sensual, transcendent time of all; and that planning for it, especially during one’s middle years, can help make this so.

Wholeness

Arnheim’s staircase made me realize how important it can be to see life as an interplay between one’s beginning, middle, and end. I found out that if we understand more deeply what Act I and Act II are (or were) about, who we are (or were becoming) during those foundational years, what dreams are still to be realized and which regrets addressed, then we can see Act III as a coming to fruition, rather than simply a period of marking time, or the absence of youth. We can understand it not as the far side of the arch—as the decline after the peak—but as

a stage of development

in its own terms. We can experience it as part of the staircase—with its own challenges and joys, pitfalls and rewards, a stage as evolving and as satisfying and different from midlife or youth as adolescence is from childhood.

In 1996, Erik and Joan Erikson wrote, in

The Life Cycle Completed,

“Lacking a culturally viable ideal of old age, our civilization does not really harbor a concept of the whole of life.”

4

The old ways of thinking about age, the fears of losing our youth and facing our own mortality, have kept us from seeing Act III as a vital, integrated part of our overall story, the potential-filled culmination of the first two acts. This old thinking is even more tragic now, in light of the extension of the life span. It can rob us of wholeness, and it can rob society of what we each, in our ripeness, have to offer.