Pierre Berton's War of 1812 (83 page)

Read Pierre Berton's War of 1812 Online

Authors: Pierre Berton

Barclay’s flagship,

Detroit

, is the largest craft on the lake—126 feet in length—at least fifteen feet longer than either of Perry’s twin brigs,

Niagara

and

Lawrence

. But firepower counts more than size, and here Perry has the advantage, especially at close quarters. Long

guns are most effective at eight hundred yards. At three hundred yards, the stubby carronades can do greater damage. Here, Perry’s ships can shatter the British fleet with a combined broadside of 664 pounds. The British, who prefer the longer range, can reply with only 264 pounds of metal. Barclay is also short of trained gunners and seamen. Of his total crew of 440, at least 300 are soldiers, not sailors. But three of every five men in Perry’s crews are seamen.

Barclay has one advantage only. Perry’s two largest vessels,

Lawrence

and

Niagara

, are inferior to him in long-range firepower. At long range, for instance, the American flagship faces nine times its own firepower. No wonder Perry is desperate to fight at close quarters.

Barclay may not have statistics, but he does have a rough idea of the two fleets’ comparative strength. He has carefully taken the measure of the opposing squadron off Amherstburg, climbing to the highest house in the village to examine the vessels through his glass. His strategy is the opposite of Perry’s. He must use his long guns to batter the Americans before they can come within range with their stubby carronades. It must be frustrating to realize that so much depends on forces over which he has no control. If he has the “weather gauge”—that is, if the wind is behind him, giving him manoeuvrability—then Perry will be in trouble. But if Perry has the gauge, the wind will drive him directly into the heart of the British fleet.

Tomorrow will tell the tale. For all Barclay knows, it may be his last day on earth. He may emerge a hero, honoured, promoted, decorated. More likely, he will have to shoulder the blame for defeat.

But Barclay is not the kind of man to consider defeat, for he was cast in the mould that has made Britain master of the seas. He is only twenty-eight, but like his contemporaries he has spent more than half his life—sixteen years—in the service of the British navy. Perhaps now his mind harks back to that soft May day in 1798 when at the age of twelve—a small, plump child with rosy cheeks and dark eyes—he took leave of his family and boarded a coach to join a British frigate at Greenock, weeping bitterly because, as he told

a sympathetic innkeeper’s wife, “I am on my way to sea and will never see father, mother, brothers and sisters again.” It is a scene that Barclay cannot put out of his mind. The life of a teenaged midshipman in the British navy is no feather bed. Young Barclay was “ill used,” to quote a scribbled remark in an old family register.

It has not been an easy life or a particularly distinguished one. Barclay is a run-of-the-mill officer, no better, certainly no worse, than hundreds of others in the navy that Nelson shaped. “Ill used” fits his career—a wound at Trafalgar, an escape from drowning when a boat capsized, an arm lost in an engagement with the French. He carries with him a combination knife and fork with which to cut and eat his meat, one-handed. His rank is low; he is called a captain because he commands a ship on Lake Erie; officially he is only a commander. Compared with the big three-decked ships of the line, which are the navy’s pride, this crude vessel

Detroit

, hammered together from green lumber and awkwardly rigged, must seem pitifully inadequate. Yet it is a command. He is painfully aware that he is second choice: the post was first offered by Yeo to William Howe Mulcaster, who promptly refused it, believing, quite rightly, that there is no honour in a badly equipped, undermanned fleet on a lake that the high command clearly views as a backwater. So the command has devolved on Robert Heriot Barclay, His Majesty’s humble, obedient, and sometimes ill-used servant. How will fate, fortune, wind, and circumstance use him in the approaching conflict? Tomorrow will tell.

PUT-IN BAY, LAKE ERIE, SEPTEMBER 10, 1813

Sunrise. High up on the mast of

Lawrence

, Perry’s lookout spies a distant silhouette beyond the cluster of islands and cries out, “Sail, ho!”

Perry is out of his bunk in an instant, the cry acting as a tonic to his fever. Up the masthead goes his signal:

Get under way

. Within fifteen minutes his men have hauled in sixty fathoms of cable, hoisted the anchors, raised the sails, and steered the nine vessels for a gap between the islands that shield the harbour.

The wind is against him. He can gain the weather gauge by beating around to the windward of some of the islands; but that will require too much time, and Perry is impatient to fight.

“Run to the lee side,” he tells his sailing master, William Taylor.

“Then you will have to engage the enemy to the leeward, sir,” Taylor reminds him. That will give the British the advantage of the wind.

“I don’t care,” says Perry. “To windward or leeward, they shall fight today.” Taylor gives the signal to wear ship.

The fleet is abustle. The decks must be cleared for action so that nothing will impede the recoil of the guns. Seamen are hammering in flints, lighting rope matches, placing shot in racks or in circular grummets of rope next to the guns. Besides round shot, to pierce the enemy ships, the gunners will also fire canister and grape—one a formidable cluster of iron balls encased in a cylindrical tin covering, the other a similar collection arranged around a central core in a canvas or quilted bag. Perry’s favourite black spaniel is running about the deck in excitement; his master orders him confined in a china closet where he will no longer be underfoot. As the commander collects the ship’s papers and signals in a weighted bag for swift disposal in case of surrender, his men are getting out stacks of pikes and cutlasses to repel boarders and sprinkling sand on the decks to prevent slipping when the blood begins to flow.

Usher Parsons is setting up a makeshift hospital in

Lawrence’s

wardroom. The brig is so shallow that there is no secure place for the wounded, who must be confined to a ten-foot-square patch of floor, level with the waterline, as much at the mercy of the British cannonballs as are the men on the deck above.

Suddenly, just before ten, the wind shifts to the southeast—Perry’s Luck again. The Commodore now has the weather gauge. Slipping past Rattlesnake Island, he bears down on the British fleet, five miles away. Barclay has turned his flotilla into the southwest. The sun bathes his line in a soft morning glow, shining on the spanking new paint, the red ensigns, and the white sails limned against a cloudless sky.

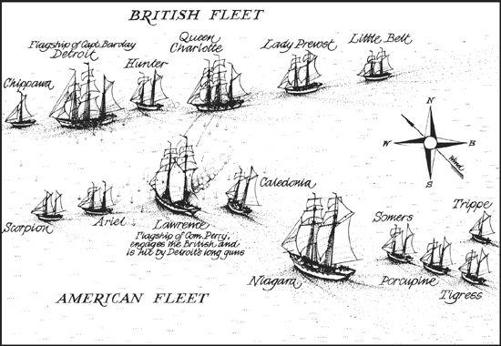

Staring at the fleet through his glass, Perry realizes that Barclay’s line of battle is not as he expected. A small schooner,

Chippawa

, armed with a single long eighteen-pounder at the bow, leads the van, followed by a big three-master, which must certainly be

Detroit

. Perry had expected the British lead vessel to be the seventeen-gun

Queen Charlotte

, designated as Elliott’s target.

He signals Elliott, up ahead on

Niagara

, to hold up while he draws abreast to question Captain Henry Brevoort, Elliott’s acting marine officer, who, being a resident of Detroit, is familiar with the British squadron. Brevoort points out the small brig

Hunter

, standing directly behind

Detroit

, and

Queen Charlotte

behind her, followed by the schooner

Lady Prevost

and a small sloop,

Little Belt

.

Perry changes his battle order at once in order to bring his heaviest vessels against those of the enemy. The ambitious Elliott, who had originally asked to be in the forefront, “believing from the frequent opportunities I had of encouraging the enemy, that I could successfully lead the van,” is moved farther back, much to his chagrin; Perry himself intends to take on Barclay. Two American gunboats,

Scorpion

and

Ariel

, will operate off Perry’s bow to act as dispatch vessels.

Caledonia

, now in line behind

Lawrence

, will engage the British brig

Hunter

. Elliott in

Niagara

will follow to take on the larger

Queen Charlotte

. The four smaller vessels will bring up the rear.

Perry has all hands piped to quarters. Out come tubs of rations, bread bags, and the standard issue of grog; and out comes the flag that Perry has prepared for this moment.

“My brave lads,” he cries, “this flag contains the last words of Captain Lawrence! Shall I hoist it?”

A cheer goes up. Even the sick—those who can walk—come out as Perry, moving from battery to battery, examining each gun, murmurs words of encouragement, exchanges a joke or two with those Kentuckians he knows best, and saves a special greeting for the men from his home state of Rhode Island, who make up a quarter of his fleet:

“Ah, here are the Newport boys!

They

will do their duty, I warrant!”

The Battle of Lake Erie: 12:15 p.m

.

And to a group of old hands who, with the experience of earlier contests, have removed their cumbersome headgear and tied handkerchiefs around their brows:

“I need not say anything to you:

you

know how to beat those fellows.”

A silence has descended on the lake. The British line, closed up tight, waits motionless in the light breeze. The American squadron approaches at an acute angle of fifteen degrees. The hush is deathly. To David Bunnell, a seaman aboard

Lawrence

, it resembles “the awful silence that precedes an earthquake.” Bunnell has had a long experience at sea, has served, indeed, in both navies, but now finds his heart beating wildly; all nature seems “wrapped in awful suspense.” In the wardroom below, its single hatch closed tight, the lone surgeon, Usher Parsons, sits in the half-light, unable to shake from his mind the horror he knows will shortly be visited upon him. He cannot curb his imagination, which conjures up dreadful scenes mingled with the hope of victory and the prospect of safe return to friends and kin.

At the guns, the men murmur to each other, giving instructions to comrades in case they should fall, relaying messages to wives and

sweethearts. In his cabin, Perry rereads his wife’s letters, then tears them to shreds, remarking that no enemy shall read them, turns to his friend Hambleton, and declares soberly: “This is the most important day of my life.”

Slowly the distance between the two fleets narrows. Minutes drag by; both sides hold their breath. Perry has little control over the speed of his vessels—the gunboats at the rear, being slower, are already lagging badly behind.

One mile now separates the two flagships. Suddenly a British bugle breaks the silence, followed by cheering. A cannon explodes. To Dr. Parsons in the wardroom below, the sound, after the long silence, is electrifying. A twenty-four-pound ball splashes into the water ahead; the British are still out of range.

The American fleet continues to slip forward under the light breeze. Five minutes go by, then—another explosion, and a cannon-ball tears its way through

Lawrence’s

bulwarks. A seaman falls dead, killed by a flying splinter. The British have found the range. “Steady, boys, steady,” says Perry.

An odd whimpering and howling echoes up from below. It is Perry’s spaniel. The British cannonball has torn its way through the planking of the china closet, knocking down all the dishes and terrifying the animal, who will bark continually during the battle.

Perry calls out to John Yarnell, his first-lieutenant, to hail the little

Scorpion

, off his windward bow, by trumpet. He wants her to open up on the British with her single long thirty-two. He himself orders his gunners to fire

Lawrence’s

long twelves, but without effect: the British are still out of range.

Barclay’s strategy is now apparent. Ignoring the other vessels in Perry’s line,

Hunter, Queen Charlotte

, and the other British ships will concentrate their combined fire on

Lawrence

—a total of thirty-four guns. Barclay intends to batter Perry’s flagship to pieces before she can get into range, then attack the others piecemeal. The British vessels are in a tight line, no more than half a cable’s length (one hundred yards) apart. At this point, Perry’s superior numbers have little significance, for, as he pulls abreast of the British, his gunboats

are too far in the rear to do any damage. He signals all his vessels to close up and for each to engage her opponent. At 12:15 he finally brings

Lawrence

into carronade range of

Detroit

, so close that the British believe he is about to board.

Now, as the thirty-two-pound canisters spray the decks of his flagship, Robert Barclay suffers a serious stroke of ill fortune. His seasoned second-in-command, Captain Finnis, in charge of

Queen Charlotte

, has been unable to reach his designated opponent, partly because the wind has dropped and partly because Elliott, in

Niagara

, has remained out of range. Finnis, under heavy fire from the American

Caledonia

, determines to move up the British line, ahead of

Hunter

, and punish

Lawrence

at close quarters with a broadside from his carronades. But just as his ship shifts position, he is felled by a cannonball and dies instantly. His first officer dies with him. A few minutes later the ship’s second officer is knocked senseless by a shell splinter. It is now 12:30.

Queen Charlotte

, the second most powerful ship in the British squadron, falls under the command of young Robert Irvine, a lieutenant in the Provincial Marine who has already shown daring in two earlier battles. But daring must take a back seat to experience. Irvine is no replacement for the expert Finnis, and all he has to support him is a master’s mate of the Royal Navy, two boy midshipmen from his own service, a gunner, and a bo’sun. Barclay has lost his main support.