Pieces of My Heart (17 page)

Read Pieces of My Heart Online

Authors: Robert J. Wagner

I had no sense of the old order dying; rather, I was focused on the wonderful pictures that were being made in England, France, and Italy. I meant to get into some of them. No, that isn’t correct. I

had

to get into some of them. This wasn’t about want, this was about need; it was a question of survival.

On the trip to the airport, on the plane to London, I tried hard to cling to my residual optimism, as I have all my life. I believed that the future had to be better than the recent past. All I had to do was be there. All I had to do was strike a match.

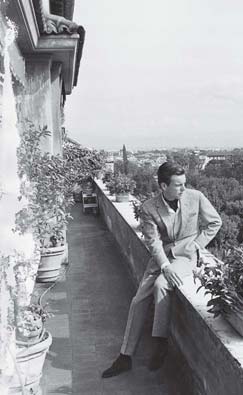

A heartbroken actor in Rome, on the terrace of his new apartment, 1962.

(PHOTOGRAPH BY ARALDO DI CROLLALANZA

)

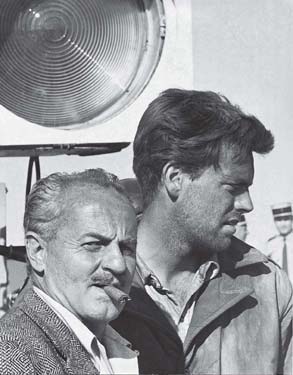

With my friend and mentor Darryl Francis Zanuck on the set of

The Longest Day

. (

THE LONGEST DAY

© 1962 TWENTIETH CENTURY FOX. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED.

)

I

set up shop in London, where Kate Hepburn helped me get a house. After a month or two, the situation with Natalie hadn’t appreciably altered. She was still involved with Warren, and the press was whooping it up like jackals, with me as the prey. In Hollywood, we hadn’t had any contact after the separation—everything was handled through intermediaries—but she was never out of my head.

In September 1961, I called her from the apartment of the producer James Woolf. I told her that I had an opportunity to be in a movie, but that a movie, any movie, was less important to me than being with her.

“I’m supposed to go to Florida,” she said. I knew that Warren was making a movie there with John Frankenheimer.

“What do you want to do?” I asked her.

There was a pause, and she finally said, “I’m going to Florida.” I hung up. It had all been awkward; I would much rather have talked to her face-to-face. There was nothing else to say, and now there was nothing else to do. The legalities were all handled through third parties, and for a long time we were out of contact. When she was nominated for an Oscar for

Splendor in the Grass

, I wrote her a note: “I hope with all my heart that when they open the envelope, it’s you.”

God help me, I was still in love with her. During all the time we were apart, she never left me. Every person has a favorite lover, the person who transforms your life and makes it better than it ever had been before. For me, that was Natalie.

Leaving meant she didn’t have the problem of dealing with me and feeling guilty—about Warren, about her career going up and mine coming down. I didn’t miss the public us, the “RJ and Natalie” thing. That never entered the picture.

I missed her loving me

. She was one of those girls who had a gift for life. She was the sort of woman everybody loved, a wonderful human being with great humor and empathy, and we had found everything together. Other than Barbara Stanwyck, she was the first woman who lived up to my idea of what a woman could be.

But I had to face reality. Natalie filed for divorce in April 1962, and it was granted that same month. I stayed in Europe, and my attorney didn’t contest it. We had been married three years and seven months—not a long time, but up to that point, the best years of my life.

T

he second picture under my deal at Columbia was

The War Lover,

with Steve McQueen. It was all right, although Steve and I both felt it could have been better. Neile, Steve’s wife, was on the set, and she was a great stabilizing force for him. Steve had just finished

The Magnificent Seven

for John Sturges and was approaching stardom cautiously. Steve didn’t like Shirley Ann Field, and I did, a lot, especially offstage, so I worked with her in most of her scenes. She was a lovely girl who had caught a big break with Olivier on

The Entertainer

and didn’t really follow it up, but she helped take my mind off Natalie for a time.

I found Steve very self-conscious, and very competitive, even about small things. For instance, Steve was about five-nine, smaller than me, so he made sure to never have his wardrobe hanging next to mine where anybody could see it. It’s the sort of thing that strikes me as wasted effort—why not use that emotional energy for something constructive? Steve was such a complicated man: always looking for conflict and never really at peace. That kind of personality can be very wearing, to say the least.

But Steve was a good friend at a difficult time in my life. The subject of Natalie came up often, and he knew I was brokenhearted. He was very sympathetic, and I grew to like Steve a lot; I think he trusted me as much as he trusted anybody, which wasn’t all that much.

Later, when I was married to Marion, my second wife, the four of us became close, and Steve and I would ride our motorcycles in the desert together, then have dinner and drink. He loved antique airplanes; he had a hangar near Santa Barbara where he kept his biplanes.

While I was making

The War Lover,

Darryl Zanuck called and asked me to be in

The Longest Day,

his epic about D-Day. He didn’t have to ask twice. Working on

The Longest Day

was great fun, but it was also one of those films filled with a purpose—to tell a great story that had never been told before. I was thrilled to find that my scenes were to be shot at Point du Hoc, and Darryl directed them himself. Most of the actors were on “favored-nation status”—meaning we all got the same money—so there was very little competitiveness.

It was all very felicitous; I had been through such a terribly dark time, and it seemed that the clouds were lifting. It was at this time that I flew from London to Paris to shoot my scenes for

The Longest Day

. I was rushed through customs, and there were about three hundred people to meet me at the Georges V. Hey, I’m an actor. I love it; I think I’m doing just great. I took my sweet time getting through the crowd, signing autographs and milking it, and I finally got to the front desk. I said that I’d like my suite, and the man behind the desk said, “What’s your name?” I looked at him somewhat coldly and said, “Robert Wagner.”

That night I went out with Eddie Fisher and Elizabeth Taylor, who were taking a break from the early stages of

Cleopatra

. We had a sensational time. Too sensational. By the time I got back to the hotel, I was thoroughly blitzed. I walked up to the desk and asked for my key. The man behind the desk said, “What’s your name?” I grabbed him by the lapels and said, “You son of a bitch, my name is…” And then I looked at him through my alcohol haze and realized that this was not the same man. And then I looked around the lobby carefully and realized that this was not the Georges V. I dropped the man’s lapels, apologized profusely, then found my way to the right hotel. Easily one of the most embarrassing moments of my life.

I know that Eddie Fisher ended up as something of a joke, but he had a wonderful way with women, and on the basis of the times I spent with them, he and Elizabeth were good together. The thing about Eddie professionally was that he had absolutely no sense of rhythm, which makes singing pretty difficult. He started drinking because he thought it would relax him and make him as loose as Dean Martin. He could never understand how guys like Dean did what they did. But then, they had rhythm.

The Longest Day

reunited me with Mother Mitchum, who was as he had been. We were walking down the Champs-Élysées together when a woman came up to him and said, “Mr. Cooper, would you autograph my passport?” He took her passport and wrote, “Fuck you, Gary Cooper.”

The thing about Mitchum was that you never knew which direction he would go. He was extremely bright, and his responses could be variable: he could laugh something off, or he could get very dark and wintry. Like the time in the 1940s when he got caught smoking marijuana. Now, when has a movie star actually done time, before or since? But Mitchum was not just bright, he was brave as well. When he got busted, he said, “Fuck it,” took the fall, and did the time. As far as he was concerned, it was no big deal.

I think that element of authentic strength and danger was what made him so compelling on screen. The general theory about Mitchum was that he really didn’t give a shit. Not true. He gave a shit—he just didn’t want to get caught giving a shit.

The thing about the movie business is that it’s full of legendary characters, not all of whom are famous. One of the reasons

The Longest Day

was such great fun was Ray Danton. Ray was one of those actors who put his energy into his life, not his career. At the time we did

The Longest Day,

Ray was shacked up in a hotel with two very beautiful girls. There were two-way mirrors in the bedroom, and the hotelier was making a great deal of money charging people to watch Ray make love to two women at once. Ray never knew how much money this guy was making off his remarkable prowess!

Years went by, and Ray was now directing television. He directed a couple of episodes of

Switch

with Eddie Albert and me. Sharon Gless and Ray hit it off professionally, and she kept him with her as her star rose on television. When Ray developed terrible kidney problems, she kept him working on

Cagney and Lacey

. Ray no longer had the stamina to direct, but he could hold script, and Sharon made sure that Ray always had a job so he could keep his medical benefits.

It goes without saying that Sharon is a special lady. Occasionally, things happen in this business that make you realize there are people who live by a higher law than the one of the jungle.

W

hen I got to London, I started taking out Joan Collins again. Joan was always companionable, always fun. As a matter of fact, I was the one who introduced Joan to Anthony Newley, whom she eventually married. We had gone to see

Stop the World, I Want to Get Off,

which Tony wrote and in which he starred, and that brought Joan and me to a screeching halt. I asked Joan to come to Rome with me, but she didn’t want to go because (a) she didn’t like to fly, and (b) she wanted to be with Tony Newley.

So I went on ahead and met Marion Marshall in Rome. Marion had divorced Stanley Donen and had two wonderful sons, Josh and Peter, as well as a magnificent apartment in Rome. I was immediately enthralled with Marion and her boys, and very soon we had a life together.

Marion was a year older than I was, and she had been a successful model before she got to Fox around the same time as Marilyn Monroe. When Marion married Stanley Donen in 1952, she quit acting to raise their two kids—Peter, who was born in 1953, and Josh, who came along two years later. The marriage broke up in 1959.

Marion was the right woman for me at the right time, and she gave me a lot. For one thing, she began to heal the wounds left by the divorce from Natalie. For another thing, my friends told me that she gave me an international quality that hadn’t been there before. She was a refining influence in matters of clothes and attitude.

And magically, things started to happen in a positive way for me, which was certainly a switch from the last couple of years. Besides my new love for Marion, Josh and Peter became my sons every way but legally. And a wonderful, empathetic agent named Carol Levi began handling me. Carol was based in the William Morris office in Rome and understood exactly what I wanted from the next phase of my career.

Carol helped get me cast in

The Condemned of Altona,

a fine picture with Sophia Loren directed by the great Vittorio De Sica.

The Condemned of Altona

was based on a play by Jean-Paul Sartre, and Vittorio was without question one of the best directors in the world. I was back doing what I wanted to do: making good pictures, working with great directors.

Years before we did the De Sica picture, I had met Sophia Loren when she came over to Fox after shooting

Boy on a Dolphin

in Europe and the studio set up a publicity event for her. Buddy Adler was running the studio then, and we were all supposed to toast her for the cameras, but I had neglected to get a glass of champagne. Sophia promptly handed me her glass. A small thing, but I would learn that Sophia is more than an actress, she is a woman of true graciousness. She sees more than her reflection in the mirror; she sees the people around her and acts accordingly.

There’s a famous still of Sophia looking askance at Jayne Mansfield’s breasts. That picture was taken at Romanoff’s. I was on my way there when I passed Jayne in her car. Her window was down, and she was applying rouge to her nipples. I knew her, so I stopped the car. “Looking good!” I said, but what I really wanted to know was what the hell was she doing? It turned out to be a setup to draw attention away from Sophia, who was the hot new girl in town. It worked, for that one night, but Sophia had the career that Jayne could only dream about.

During

The Condemned of Altona,

I fell madly in love with Sophia. Who wouldn’t? Most nights she would cook for me, and on top of everything else she’s a splendid cook. She was very loyal to Carlo Ponti, although I understand she had an affair with Cary Grant during

The Pride and the Passion.

Sophia had never had a father in her life—her own father disappeared when she was quite young—and Carlo had found her at a very young age and carefully built her career, and she wasn’t about to betray him. I could certainly appreciate that loyalty; I could also respect it. Sophia mostly lives in Switzerland now, but we talk all the time.

As much as I adored Sophia and Vittorio De Sica, I grew to detest Maximilian Schell. He’d won the Oscar for best actor the year before for

Judgment at Nuremberg,

and he was enthralled with his own accomplishments. Of course, Sophia had also won an Oscar, for

Two Women,

but you would never have known it. Her attitude was that of a professional going to work—no more, no less.

The night before we shot a crucial scene, Schell came to my hotel room and gave me a big talk about our playing brothers and how we had to get into the essence of the scene we would be shooting. The next day Schell was behind the camera giving me the off-camera lines for my close-ups, and the entire time I was acting he was shaking his head.

Brothers, my ass!

It was stunningly unprofessional, not to mention calculatingly rude, and the first and only time I’ve ever seen anybody pull anything like that. What was really upsetting him was the fact that Sophia and I were very close, and he didn’t like that.

Schell’s rudeness became his modus operandi; one day, when he was doing a scene with Sophia, he asked me to leave the set because he found my presence disconcerting. We were in Livorgno at the time, and I seriously thought about taking a club to his head, but Carlo Ponti talked me out of it. Of course, Schell being Schell, on those occasions when I’ve run into him in later years, he’s all over me with phony bonhomie. “Oh, darling, it’s so good to see you”—total showbiz bullshit.