Pieces of My Heart (12 page)

Read Pieces of My Heart Online

Authors: Robert J. Wagner

S

ome people who have gone through a quick rise to stardom report feeling a loss of control, but I never felt that. I was doing exactly what I wanted to do.

It’s possible that I had too much of an allegiance to the trappings of my stardom. Once, around this time, I was in a convertible with Watson Webb and Rory Calhoun. I was studiously going through a pile of my fan mail when Rory grabbed it and heaved it up and out of the car. It scattered through the air like confetti, and Rory thought my reaction was the funniest thing he’d ever seen.

Watson Webb was a descendant of two great fortunes. His father, James Watson Webb Sr., was a descendant of Cornelius Vanderbilt. His mother was the daughter of the founder of the American Sugar Refining Company. After Watson graduated from Yale in 1938, he decided to avoid going into either of the family businesses. Instead, he went to Hollywood, where he became one of Zanuck’s most trusted film editors. He was very comfortable editing film in the conventional style of the time, but he was also adept with much edgier, more violent movies. Among the pictures Watson cut were

The Dark Corner, Kiss of Death, Broken Arrow, A Letter to Three Wives,

and

The Razor’s Edge

. The last picture he edited had been

With a Song in My Heart,

after which he quit Fox and dabbled—in directing, in investing, in philanthropy, in being a great friend.

Watson had a house in Brentwood, and he also had a place at Lake Arrowhead that he had bought from Jules Stein, the founder of the Music Corporation of America—MCA. Watson was a total blue-blooded gentleman. Everybody assumed he was gay, but he was so discreet that there was no real way of telling, which was precisely the way he wanted it. Years later, when he stepped up and lent me a hand at a desperate time, he would put me forever in his debt.

I

think I began to kick in as a professional about the time of

Broken Lance

. When I started at Fox, I had been under the illusion that you became an actor by practice. It was, I thought, like learning to play tennis or golf: you went to the pros and let them teach you.

It took me a while to realize that I had to learn to use myself to get where I needed to go. The main thing I had to learn was to get out of my own way. “How do you do it?” I had asked Spence, but it doesn’t happen that way. I was twenty-one years old when I worked with Cagney and Ford, and it was very hard to get the fact that I was working with Cagney and Ford out of my head. I was still overwhelmed by the reality of the filmmaking process and hadn’t yet learned to play the reality of the scene.

In other words, my primary problem as an actor was self-consciousness. The great trick of acting is to make it look easy, as if you’re not acting at all. If the audience thinks to themselves,

Jesus, I could do that

, then you’re succeeding. In line with that, the test of an actor is not whether he can cry, but whether he can make the audience cry.

For the most part, my social circle disdained “the Method,” but I’ve always been in favor of whatever makes an actor comfortable in his skin and frees him up—something that helps get an actor where he needs to go. I went to the Actors Studio in New York, and I observed. I could see them looking at me and rolling their eyes. They thought I was an asshole—the pretty kid who had made

Prince Valiant

and been laughed at.

That just made me determined to be better. I didn’t want to be a joke; I wanted to be real. There was a snobbery about some of the people who gravitated to the Method that I objected to. They loved to talk about acting, then talk some more, but I’m not sure acting should be talked about that much. You can learn a lot more by doing than by talking, and acting, after all, is doing. And by doing, you learn.

For instance, I watched Cary Grant working on

An Affair to Remember

for Leo McCarey. He came offstage after doing a scene and told me, “I learned something interesting today. I learned how to breathe in a scene.”

Now, this is 1956, and Cary Grant was, well, Cary Grant; he’d been doing it with a matchless grace for nearly a quarter-century at that point, and he had just realized that a lot of times when you’re acting you’re unconsciously holding your breath waiting for your cue, and that’s not a good thing.

Cary, of course, is the ultimate example of what I’m talking about. He had to work very hard to acquire the sense of ease that he displayed as an actor. The process by which Archie Leach of Bristol, England, became Cary Grant of Hollywood can’t be broken down by endless conversation. Yet Cary wasn’t just smooth; he was emotionally real and always present. Watch him in a scene and notice how focused he is, how intently he listens to the other actor. To acquire all that skill and to make it look easy is enormously hard.

The great thing about the studio system, of course, was that it was a classic apprenticeship system. I watched Gary Cooper and Cary work, and I always had this subliminal feeling that, if I worked hard enough, someday I’d be standing where they stood. But I never had a sense of entitlement, which a lot of young actors—and a lot of young people—do today.

A

fter Barbara there were a lot of women, but the one who stands out was Elizabeth Taylor. I had met her at one of Roddy McDowall’s parties before I was in the movie business, and like every other male animal around the world, I was crazy about her. People always talk about her spectacular beauty or her violet eyes, but emphasizing those features overlooks her emotional appeal, which I think is centered on her vulnerability. She is a wonderful woman in a very unusual way—great humanity and great sensuality are not commonly packaged together, but when they are, the whole world knows it.

Some beautiful women are passive in the bedroom. They’re gorgeous, they know they’re gorgeous, they know that you know they’re gorgeous, and they don’t feel the need to do anything above and beyond being gorgeous.

Elizabeth was not one of those women. Being with her was like sticking an eggbeater in your brain.

I loved her, and I think she loved me. But on the practical level, Elizabeth was not the woman I needed in my life. With Elizabeth, there was a great deal of maintenance. This is not a woman who gets up in the morning and fixes breakfast. By the time she comes downstairs for breakfast, it’s time for dinner. She’s not floating in the pool with you on a lazy Sunday afternoon, handing magazines back and forth. Elizabeth’s life is built completely around Elizabeth, and she needs a man to service her life 24/7.

She also has the most spectacularly bad luck in terms of illness I’ve ever encountered, and it needs to be emphasized that Elizabeth is far from a hypochondriac. Just as there are people who are accident-prone, there are people who are illness-prone, and Elizabeth is certainly one of them. One time when I was visiting her, she was getting into a car and the man helping her slammed the door. It blew out her eardrum. Just thinking about Elizabeth’s physical troubles is exhausting; I can’t imagine what it must be like to have to live with them.

In any case, this was a period when I was enjoying my freedom. I first saw Anita Ekberg when she came to RKO as a starlet. This was long before Federico Fellini made her, Marcello Mastroianni, and the Trevi Fountain immortal in

La Dolce Vita

. I took one look at Anita and was reduced to the level of a hormonal schoolboy. Luckily, she responded to me the same way I responded to her. The fact that she had been staked out by Howard Hughes was irrelevant to me.

Anita and I were enjoying ourselves in an apartment in Westwood when there was a knock on the door. I looked out the window and…Sweet Jesus!…it was Howard Hughes. His truculent reputation preceded him; he was not a man you wanted to get into an argument with. I threw on my clothes and went out the back door, with Howard Hughes running after me. I remember very distinctly that I was running across the lawn when I kicked a sprinkler head, opened up a very nasty slash in my brand-new shoes, lost my balance, and tumbled ass over teakettle. I was not only young, I was nimble; I sprang up and kept running.

I would like to go on the record as saying that an afternoon with Anita Ekberg was worth the destruction, not just of a pair of shoes but of an entire wardrobe and probably a Mercedes-Benz showroom as well.

During the few months when I was hot and heavy with Anita, my mother noticed that she wasn’t seeing me much. “What are you doing with your weekends?” she asked me out of the blue one day. My mind was a million miles away—probably on Anita—and I blurted out something about playing tennis at the Bel-Air Hotel.

She gave me a strange, amused look and pointed out that the Bel-Air Hotel didn’t have tennis courts.

Busted.

I

got a copy of Frank Nugent’s script for

The Searchers

, which John Ford was going to direct for Warner Bros. The part of Martin Pawley leaped out at me. It was a part I could play, and I knew it; had he hired me for

The Searchers

, Ford could have knocked me on my ass on a daily basis. I just loved that script; I had enough sense to know that it would make a wonderful movie, especially with Duke Wayne as Ethan Edwards and Ford directing. The greatness of that picture, its dramatic strength, was already evident on the page. I could see it, and I knew Ford’s visual splendor would put it over the top.

You’ll remember that Ford had called me “Boob” and treated me like a dog on

What Price Glory?

No, let me rephrase that. There are no conditions under which I would treat a dog as badly as John Ford treated me on that picture. Actually, Ford liked dogs a lot more than he liked actors. I knew all this, and I swallowed my pride and scheduled an appointment with Ford.

There’s a certain reality of show business that the public doesn’t understand: it’s a business for whores, especially when it comes to actors. We have to put ourselves out there for those few good parts that come along, even if those parts are controlled by people we don’t like, and who may not like us. But we put on our best clothes and smile and go out and try to sell ourselves. Not pleasant, but reality.

I took a deep breath and went to see Ford.

“You’d like to play the part, wouldn’t you?” he said.

“Yes, Mr. Ford.”

He didn’t waste my time or his. “Well, you’re not gonna play it. Jeff Hunter’s going to play it.”

I knew John Ford well enough to realize there was no way you were ever going to argue him out of a casting decision, or anything else. I thanked him for his time and got up to leave. I got to the door and Ford spoke up.

“Boob?”

“Yes, Mr. Ford?”

“You really want to play the part?”

“Very much, Mr. Ford.”

“Well, you’re still not going to!”

That was John Ford, and whether the actor in question was Duke Wayne, Jeff Hunter, or me, you learned to accept him for what he was: a great artist with a personality that could keep you up nights—for years.

O

ne day near the end of 1956, Spencer Tracy took me over to Humphrey Bogart’s house. I had known Bogie for years because of our shared passion for boats and the sea. Bogie was distinguished as an actor by an unusual combination of dramatic power and a light touch—he could suggest dramatic and character points gracefully, and he could bring humor to heavy material. Bogie called his boat the

Santana,

and she was a sleek thing of beauty—a yawl. On board the

Santana,

Bogie was pure—not an actor on a boat, but a sailor on his boat.

Everybody in Hollywood knew that Bogie was dying, shrinking day by day from cancer. Every afternoon he would be bundled into a dumbwaiter and brought down to the first floor of the house for an hour or two of conversation with his friends, after which he would be bundled back into the dumbwaiter and return to bed.

It was an amazing experience—a salon held by a dying man. Bogie must have been in terrible pain, but he never let it show. The mood was light and mostly humorous. The conversation was about boats, pictures, and people—who was doing what. Even dying, Bogie had humor, and he gave me a touch of the needle. He asked Spence, “What the hell are you doing giving this kid costar billing?”

I took it as a straight line. “Listen,” I said, “when we work together, I’ll be happy to give you costar billing.” He laughed.

When he died in January 1957, there was no coffin, no body at the funeral. The centerpiece was simply a model of the

Santana

. People have always paid tribute to Bogie’s professionalism, the way he was a stickler about his work—one of the traits he shared with Spence. But he was also a nicer man than he liked to let on. And that model of the

Santana

showed that there was something else he took almost as much pride in as his acting: being a good sailor.

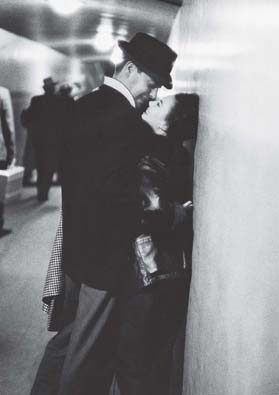

At the train station in Los Angeles, on our way to being married in Arizona.

(COURTESY OF THE AUTHOR

)