Pediatric Examination and Board Review (102 page)

Read Pediatric Examination and Board Review Online

Authors: Robert Daum,Jason Canel

7.

(C)

Any testing of children exposed to group A streptococci is unwarranted because asymptomatic carriage during an outbreak can be as high as 25-40%. Only symptomatic children should be examined, and a rapid group A streptococci test and culture should be considered.

8.

(E)

In toddlers younger than 3 years, group A streptococcal infection may present with serous rhinitis, fever, irritability, and anorexia, instead of the pharyngitis typically seen in older children. However, because the risk of rheumatic fever in this age group is extremely low in developed countries, culturing for group A streptococci is

not

recommended in this age group unless the patient is known to be at high risk for rheumatic fever or the illness occurs during a rheumatic fever outbreak. In this case, (E) (no test) therefore is the correct answer. Testing for mononucleosis or influenza is not indicated based on the symptoms. The monospot test is insensitive in a 2-year-old child.

9.

(B)

This is the classic presentation of perianal group A streptococci dermatitis (see

Figure 62-1

). It occurs more often in boys between the ages of 6 months and 1 year. Presenting symptoms and findings are itching, pain on defecation, blood-streaked stool, and a well-circumscribed erythematous rash from the anus extending outward. Recurrence rates are 40-50%. The differential diagnosis includes A, D, and E, psoriasis, and sexual abuse.

10.

(D)

Glomerulonephritis is the most serious complication associated with group A strep skin infections (and pharyngeal infections); rheumatic fever is

not

associated with skin infections caused by group A streptococci.

FIGURE 62-1.

Group A streptococcus intertrigo—perianal streptococcal cellulitis. Well-demarcated erosive erythema in the perianal region and perineum in an 8-year-old boy who complained of soreness. (Reproduced, with permission, from Wolff K, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, et al. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine, 7th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008: Fig. 177-15.)

11.

(B)

12.

(E)

Group A streptococci dermatitis, especially perianal disease, requires oral antibiotics for treatment. Topical antibiotics will be ineffective.

13.

(D)

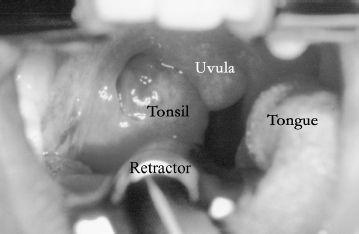

This is a classic story for peritonsillar abscess, most likely caused by group A streptococci (see

Figure 62-2

). She is experiencing trismus, the inability to open the jaw secondary to peritonsillar and lymphatic edema. If she were to open her mouth, you would find an asymmetric tonsillar bulge, perhaps with uvular and/or palatal displacement. Generally, retropharyngeal abscesses are less common in children older than 5 years because the retropharyngeal nodes that fill the potential retropharyngeal space involute before that age; thus the pathophysiology of this disease differs in adolescents and adults, in whom it is rare. Gonococcal pharyngitis should be considered among sexually active persons and can present with fever, sore throat, and greenish pharyngeal/tonsillar exudates.

FIGURE 62-2.

Open mouth view with the retractor on the tongue in a patient demonstrating medial right tonsillar displacement, palatal edema, and uvular deviation consistent with a peritonsillar abscess. (Reproduced, with permission, from Tintinalli, JE, Kelen GD, Stapczynski JS. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 6th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004: Fig. 243-1.)

14.

(B)

A CT of the neck with IV contrast will most clearly and rapidly assess for a ring-enhancing abscess or possibly a phlegmon. Fine-needle aspiration is one approach to surgical treatment but is seldom performed for diagnosis.

15.

(B)

IV antibiotics and incision and drainage are the mainstays of treatment of peritonsillar abscess (see

Figure 62-3

). Pain control is usually needed and can be supplied in oral (liquid) or IV form. Oral steroids may be useful in severe mononucleosis but not for peritonsillar abscesses.

FIGURE 62-3.

Peritonsillar abscess. Acute peritonsillar abscess showing medial displacement of the uvula, palatine tonsil, and anterior pillar. Some trismus is present, as demonstrated by patient’s inability to open the mouth maximally. (Reproduced, with permission, from Knoop KJ, Stack LB, Storrow AS, et al. Atlas of Emergency Medicine, 3rd ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2010:118. Photo contributor: Kevin J. Knoop, MD, MS.)

16.

(C)

Retropharyngeal abscess is a disease of younger children, as stated earlier, whereby infection of the lymph nodes located in the retropharyngeal space is associated with fever, sore throat, trismus, drooling, stridor, and change in voice (cri du canard: cry of the duck [a duck-quacking sound]) (see

Figure 62-4

).

FIGURE 62-4.

Retropharyngeal abscess. Lateral soft tissue neck X-ray demonstrating prevertebral soft tissue density constant with retropharyngeal abscess. (Reproduced, with permission, from Widmaier EP, Raff H, Strang KT: Vander’s Human Physiology, 11th ed. McGraw-Hill, 2008:211.)

17.

(B)

Airway occlusion in this case is a most urgent concern because it appears that the patient has a pharyngeal process. The difficulty in examining a child like this further complicates the situation, but the combination of fever, ill appearance, hyperextension of the neck, and stridor should prompt the physician to be prepared immediately for airway management. The other complications listed are all concerns with this patient but relatively less urgent. Aspiration pneumonia is a known and dangerous complication of retropharyngeal abscess.

18.

(A)

Securing the airway is the most urgent first step in this case. Radiographic investigation most often begins with lateral neck films (with neck in full extension during deep inspiration), which are evaluated for the width of the retropharyngeal space. The width of the prevertebral soft tissue should be no more than 7 mm at C2 and 20 mm at C 6. If more urgent evaluation is required, or if proper positioning of the neck is not possible, a CT of the neck with contrast is an alternative option.

S

S

UGGESTED

R

EADING

Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, et al.

Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics

. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2007.

Long SS, Pickering LK, Prober CC, eds.

Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases

. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2008.

Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, Long SS, eds.

Red Book 2009: Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases.

28th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2009.

CASE 63: A 7-MONTH-OLD WITH CROSSED EYES