Parallax View

Authors: Keith Brooke,Eric Brown

Tags: #Fiction, #Science Fiction, #Collections & Anthologies

- Foreword

- The Denebian Cycle

- Appassionata

- Sugar and Spice

- Mind’s Eye

- Under Antares

- In Transit

- Parallax Views

Parallax View

KEITH BROOKE & ERIC BROWN

foreword by Stephen Baxter

infinity plus

Parallax View

Parallax View showcases 'In Transit', written specially for this collection, a novella set in a future war-torn universe in which human expansion has come up against the implacable Kryte. Xeno-psychologist Abbott finds himself the guardian of a deadly Kryte on a mission to study it on his return to Earth. When they crash-land on the fortress planet of St Jerome, the Kryte prisoner turns the tables and takes Abbott into terrible custody. What follows is a terrifying journey across a hellish landscape towards a finale that might change the destiny of the Kryte and humanity, forever...

Plus six other stories that examine the interface between human and alien - a parallax view from two of Britain's top science fiction writers, both shortlisted for the 2012 Philip K Dick Award.

Copyright © 2000, 2007, 2013 Keith Brooke and Eric Brown

Foreword copyright © Stephen Baxter

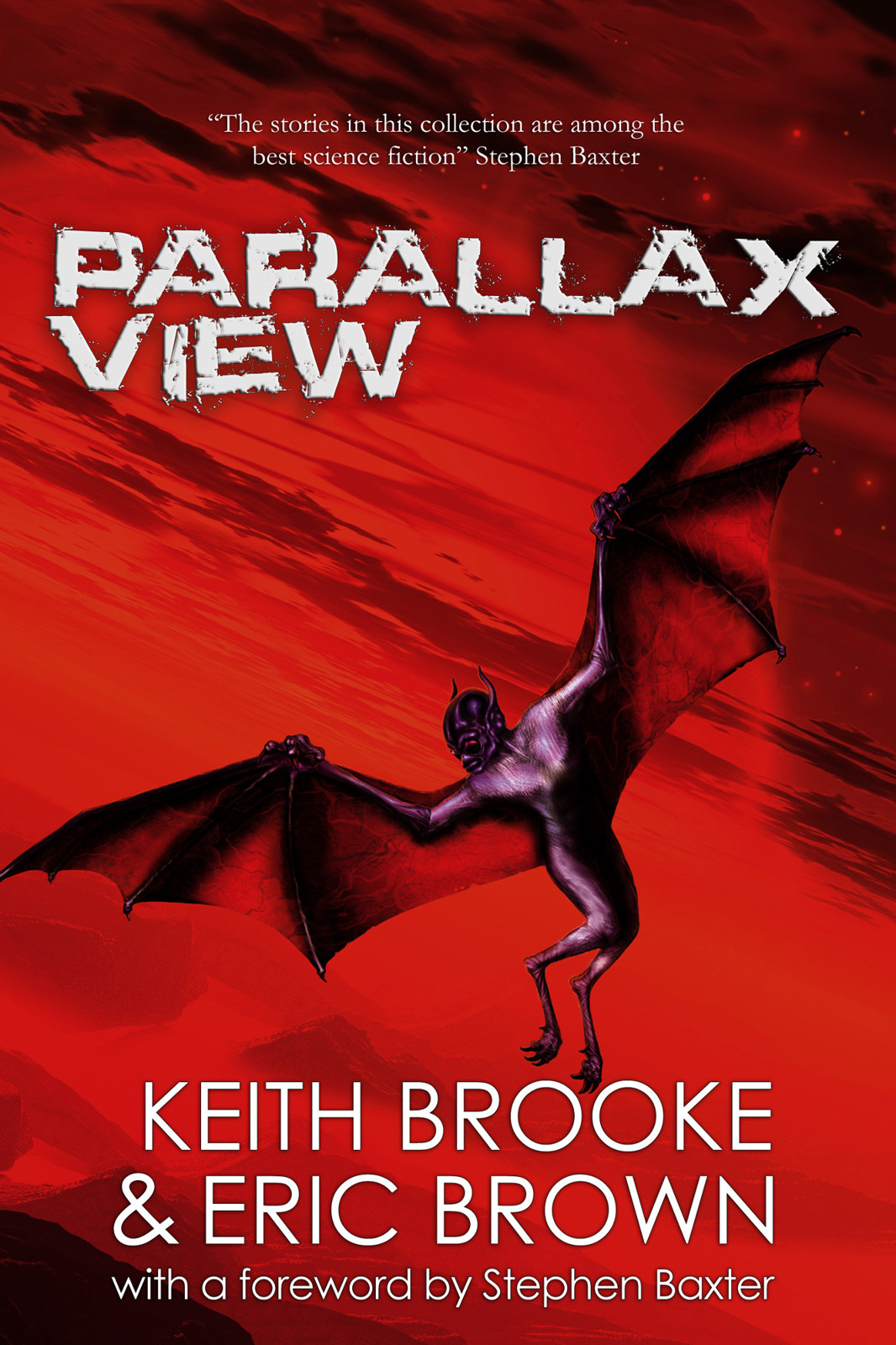

Cover copyright © Dominic Harman

All rights reserved.

Published by infinity plus

www.infinityplus.co.uk/books

Follow @ipebooks on Twitter

First published in 2000 as hardback by Sarob Press; new paperback edition, with different contents published by Immanion Press in 2007.

This edition published in 2013.

No portion of this book may be reproduced by any means, mechanical, electronic, or otherwise, without first obtaining the permission of the copyright holder.

The moral right of Keith Brooke and Eric Brown to be identified as the authors of this work has been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

Electronic version by Baen Books

Credits:

Foreword © Stephen Baxter.

‘Appassionata’ first published in

Interzone

109, July 1996. © Keith Brooke and Eric Brown.

‘Sugar and Spice’ first published in

Interzone

112, October 1996. © Keith Brooke and Eric Brown.

‘The Flight of the Oh Carrollian’ first published in

Interzone

145, July 1999. © Keith Brooke and Eric Brown. ‘Mind’s Eye’ first published in

Spectrum SF

, January 2000. © Keith Brooke and Eric Brown.

‘Under Antares’ first published in

Interzone

126, December 1997. © Keith Brooke and Eric Brown.

‘The Denebian Cycle’ first published in

Interzone

152, February 2000. © Keith Brooke and Eric Brown.

‘In Transit’ is original to the collection.

DEDICATION

To Christopher Evans, David Garnett, Robert Holdstock and David Pringle – they made the difference.

Foreword

Stephen Baxter

Science fiction is the literature of our age.

At the dawn of a new millennium our view of ourselves, our world, and our place in it is shaped by science – whether we like it or not.

The geologists have shown us that the rocks under our feet are not stable, but have been shaped by gigantic forces and events deep in the past – and that many more such events lie in wait for us in the future. Copernicus, Newton and the astronomers have taught us that our Earth, seemingly so immense and solid, is a mote suspended in space, orbiting one star out of a hundred billion, in a galaxy which swims through a universe huge beyond our imagination. The cosmologists have proved that our Earth, even the sun, is doomed to extinction – and that the future which lies in wait for us may be literally infinite.

Is it possible something of us will survive the turmoil of the present, to reach a future so distant that the brightly lit universe of our day, time’s bright morning, will seem no more than a post-Big Bang detail? Perhaps – but our children of that remote time may not resemble us. Darwin’s synthesis, perhaps the most shocking of all science, told us that even we are subject to change. According to the fossil record no mammalian species has persisted for more than a million years. Today, Homo sapiens is perhaps a hundred thousand years old ... But perhaps our children will remember us, and forgive us.

Western civilisation has been suffering future shock since the Renaissance. Science fiction is one way of dealing with that shock.

Science fiction is unique: it is the only modern literature which deals seriously with the universe – not as a static stage for our petty human dramas – but as a protagonist: as a force which can shape us even as we try to shape it, as a world beyond our grasp. Science fiction is the first literature since the classical age to take reality seriously.

But science fiction is not about cosmic doom or glossy technology, and it certainly transcends the costume dramas and action stories that clutter our movie theatres and TV screens. The best science fiction is, was and always will be about the impact of the universe on the human soul.

And the stories in this collection are among the best science fiction.

For the last ten years and more I have watched in envy as Eric Brown and Keith Brooke – separately, and more recently in collaboration – have assembled a dauntingly impressive body of mature, richly imagined, satisfying science fiction.

In their novels and short stories Brown and Brooke have prowled the boundaries of science fiction, exploring the impact of possible futures on art and music, on the texture of our relationships, on the feeling of our lives. The tools of science fiction have allowed Brown and Brooke, in the tradition of classics of the genre, to pose dilemmas beyond our current imagining, and so to shed new light on the human condition.

These are stories in the spirit of science fiction giants such as Robert Silverberg, Cordwainer Smith, Michael Coney and others. These are stories imbued with a rich intelligence and a deep sense of humanity. These are stories given to us by writers who are immersed in humanity, and yet have the strength and the clarity of vision to see beyond our current horizon. These are mature stories, tales of love and loss, of pleasure and pain.

Cherish them.

Stephen Baxter

The Denebian Cycle

It started with the firestorm.

A few seconds was all it took for the sky to slide from a deep tropical azure to a solid sheet of charcoal, the contours of individual clouds limned by repeated lightning flickers.

Corrie Asanovic pulled her cape tight across her shoulders. Deep rumbles of thunder, tuned to almost subliminal pitch, reached deep inside her. Static buzzed in the dry air, blue-white sparks jumping between the trees, echoing the lightning high above. Another dry storm, she decided, of the kind that usually drew in towards dusk. This one was earlier than usual, and far more intense.

She pulled the pack onto her back and turned to look for Sam Reubens. There was no sign of him, but that was not unusual. Rube often wandered off on his own, following some new spoor, or the cry of one of the local animal forms. Rube didn’t care about the guidelines for appropriate fieldwork, no matter how often Skip Jennings critted him. Rube was, to be blunt, one self-centred son of a bitch.

Corrie glanced at the comms decal tattooed onto the back of her left wrist. Rube, she thought, and the decal told her: 36°, 12.4m.

She spoke into the decal: “Rube, are you done yet? I think we should be getting back.”

Silence. Corrie scratched at her cheek where, despite her best efforts at hygiene, a new growth of plaque was taking hold. The plaques were a kind of colonial animal, growing like corals wherever they could take hold. She didn’t know quite where they fitted in the taxonomic schema Rube had worked out, but there was some kind of complex symbiosis going on there: a kind of animate lichen, was the best terrestrial analogy she could come up with.

They were a nuisance, whatever. It was ironic, in a way: here they were in a rich, alien environment, where there was next to nothing a human could eat, yet still the local semi-animate life-forms persisted in trying to colonise any exposed surface. Something to do with the natural oils excreted by human skin, Rube had said. He just let the plaques grow, claiming it did no harm, although Corrie was sure he did it simply to be different.

“It’s just ... storm,” he commed now, his soft voice lisping in Corrie’s ear, the sound breaking up with the storm’s interference. “Go back if you ... I’m staying out in the field.”

Bastard. He knew Corrie wouldn’t return without him: that way

she’d

be the one the skipper critted.

Corrie and Rube were about a kay and a half out from the camp. Cataloguing, sampling, recording: building up an ecofile of the 100 by 100 metre quadrant Skip had allocated them the day before. There were 48 of them in the survey team, deposited on Deneb 5 for 120 days. A low profile survey, to provide the basis for any decision on whether to make contact with the local sub-industrial sentients.

In and out: a scientific snatch squad.

The blast threw Corrie face-down on the ground.

She groaned, rolled over onto her back.

Slowly her flash-blinded vision started to return. She rubbed her eyes, and her hand brushed against her hair: normally collar-length and lifeless, now it was standing on end.

She clawed at it irrationally, feeling that somehow she had been invaded.

“Well, look at you,” said Rube, emerging from the trees. He was stripped to the waist, vivid weals of red, gold and green plaques encrusting his chest and arms – growing so thickly, he had earlier boasted, that his horn of plenty necklace had become effectively grafted into the scaled-over flesh of his neck.

She could imagine herself: sitting on her fat ass in the mud, clawing at her hair, panicking. “The lightning,” she said, feebly. “I... I think I was hit by the lightning.”

Rube laughed at her. “You’d sure know about it if you were,” he said. “Near miss, is all. You planning on sitting there all day?”

The bastard was enjoying it. According to the expedition’s constitution Corrie and Rube were equals: even Skip only governed by consensus, after all. But Rube had been working in the field for thirty or more years and this was Corrie’s first assignment. And, as Corrie kept finding herself thinking, Rube was a grade A bastard.

Would it have been any different if she’d let him fuck her, she wondered? Committed scientist that she was, that was one experiment she never wanted to try.

She scrambled to her feet.

Ten kay map

, she thought, and her comms decal showed her a low-res map of the region, the image snowstormed with static interference. Picked out in gold were 24 dots, marking the locations of the survey teams. Six of the teams were already back at base. Corrie suspected most of the others were on their way.

“We’d better get back,” she said. The air was still thick with static, the darkened sky alive with lightning: strange, spreading sheets and glows, sudden forks, a continual background flicker. This was no ordinary storm.

Rube just looked at her, then turned his back and headed into the fleshy jungle. Corrie followed him, trying hard not to stare at his scaly back, failing. The man was obscene.

She tried comming base, but all she got was a hiss of static and a patronising glance from Rube.

The trees here were all young growth: what appeared to be a mature tropical jungle was really the product of a single growing season, albeit a season that lasted a little over 35 standard years. The trunks were fleshy, packed with the kind of oils that attracted the colonies of plaques. Any journey through the jungle was an unpleasant experience: suspended from the trees were long, trailing lianas that clung like cobwebs, a cloying curtain that hosted enormous colonies of mites and bugs and god knows what else.

Corrie walked with both arms in front of her and a gauze mask over her face, but that didn’t make her passage much easier.

Rube just walked on, regardless.

Here, deeper in the jungle, the storm was diminished, but Corrie knew that it persisted from the constantly flickering light and the nasty metal taste to the air.

Some time later, she paused to brush the crap from her hair. Most of the other teams were within a kay or two of the base now, drawn as if by a magnet. She looked around, but she didn’t recognise this part of the jungle, even though they must have passed this way about ten hours before. Although she hated to admit it, this godforsaken jungle all looked pretty much the same to her.

They were only about half a kay from camp now.

Rube was out of sight. Thirty metres up ahead, her decal told her. She set out again, walking faster to catch up. She hated to admit that she depended on him, but the sense of isolation from being alone for more than a few minutes was horribly oppressive.

“Hey, Corrie,” he commed. “Better get up here quick, you hear?”

There was something different about his voice, something urgent.

She broke into a jog. “What is it?” she spoke into her wrist.

Silence.

Then, Rube’s voice, lisping softly in her ear again: “Trouble, Corrie. Big trouble.”

Seconds later she broke out of a screen of undergrowth and almost crashed into Rube’s crusty back. He was hunched to one side, talking into his wrist on a different channel. He barely glanced at her, just gestured ahead.

They had emerged on a small shelf in the face of the hill, where the jungle descended towards sludgy creek of a river they called the Brown Amazon. From this viewpoint they should be able to see the clearing where the Survey had set up base, but not now.

Dark clouds clung to the incline, billowing and twisting, plummeting down the slope towards the flood basin. At first Corrie thought it was some strange atmospheric effect: a ground-hugging, sooty fog.

But then she caught the acrid taste of smoke on the air, and she saw that the flickering she had taken for yet another lightning effect was actually caused by flames.

The forest was on fire.

Corrie barged past Rube, intent on the path that led down the escarpment towards the base camp.

After a couple of seconds she paused, turned.

Rube was still standing on the shelf, just staring at her. “What you planning?” he asked. “Going to beat out the flames with your bare hands?”

She hadn’t been planning anything. Hadn’t been thinking. She just knew she should be doing

something

.

The bastard was right, much as she hated to admit it.

Below her, the forest plunged down the escarpment, thinning in places where the bedrock broke through the thin jungle soil. About 300 metres down the slope she could see the first flames leaping across the treetops, spreading at a frightening rate from tree to tree.

“It’s the oils,” said Rube. “Everything’s full of it: trees, lianas, even the bugs.”

Just then another tree flared up like a molotov cocktail.

“Like dropping a match on gasoline,” Rube went on.

She should be able to see the base camp from here, Corrie realised. Should be able to see the off-white shell of their Vulcan lander. But all she could see was flames and smoke.

She turned away, peered at the decal on the back of her wrist. Her eyes were too fogged with tears to focus, but she was sure there were less than 24 gold dots on the map now.

The survivors assembled in a clearing, about a kay from the burned out ruins of base camp. Corrie looked around the gathering: what a sad and sorry sight, she thought. Her colleagues lay on the ground or sat against the trees, utterly bewildered and defeated by the tragic turn of events.

They were lucky, she supposed. Lucky not to have burned, like Skip and Jenny and Walter and...

Thirty-five dead, in all.

They’d had no chance, Imran had said. The walls of flame had just wrapped round the base camp like a military pincer movement. Twelve dead and the Vulcan a burned out husk, along with all the food and water supplies for the next hundred-plus days. The others had been picked off by the fire in ones and twos as they attempted to return to camp.

Earlier that day they had searched the jungle for survivors, finding none. It had been a grisly process. They had buried the bodies in makeshift graves beside the clearing, marked so that they could be exhumed when the

Darwinian

returned. More disturbing, to Corrie, than the sight of the burned and twisted corpses had been the smell of the over-cooked meat. Despite herself, it had cruelly reminded her that she hadn’t eaten for hours.

Across the clearing, Sue and Tanya hugged each other. Corrie smiled to herself, envying what they were sharing. Christ, it was going to be hard for the next few months: we need to take whatever comfort we can find.

Beside her, Rachel lay in a foetal ball. Corrie reached out and touched the back of her hand. The Somalian had lost her lover in the burned-out Vulcan, had slipped into hysteria on discovering that Ahmed had perished. Fortunately, one of the survivors had been equipped with a medical kit containing sedatives.

Now Rachel shifted a little, until Corrie found herself stroking the girl’s head in her lap.

Rube was holding forth in the centre of the clearing. “It’s simple,” he was arguing. “Survival. That’s what it’s all about now. We have 108 days until the

Darwinian

jumps back within range. When the

Darwinian

returns, we ping her with our distress beacons and they send another Vulcan down to lift us out. It’s as simple as that.”

“Rube’s right,” said Jake, the native-American zoologist. “It’s a matter of redistributing our priorities. We still have to avoid any contact with the native sentients, but we have to forget any idea of completing the survey work. We–”

“Fuck the sentients,” Rube said. “If my survival means making contact, then that’s what I do, regardless of any questionable effects on cultural evolution.”

Corrie was horrified. “How can you say that?” she demanded, surprising herself with her vehemence. “How can you say that any individual’s life is more important than the damage contact might do to an emergent culture?”

“This isn’t some college role-playing scenario now,” Rube said. “You live or you die. It’s that simple.”

“Hey, hey,” Imran said. The Australian xenthropologist looked around the group. “We’re getting hypothetical, okay? Rube’s right: we got to survive. Corrie’s right: we got to minimise our impact on the native situation. We got a little over a hundred days and we got to survive. We’re scientists, right? We’ve been studying the native lifeforms, right?” He paused, looked around the group. “Who could be in a better position to live off the land than a group of highly trained ecologists?”

Hunger.

Not the missed-a-couple-of-meals kind of hunger Corrie knew from deadline time at college. Not even the hunger she’d experienced on a survival training course, part of the prep for this expedition.

Real hunger.

Gnawing away at her gut. Every movement an enormous effort, every breath laboured. Her body running out of fuel. Head aching, brain thumping inside her skull, her vision swimming, spinning whenever she moved.

Thirst, too. So little to drink...

Stripped to the waist in the oppressive dry heat of the jungle, Corrie leaned against a grotesquely bulging tree trunk. She hugged Rachel to her. The girl, in her grief, had wordlessly sought consolation, glad to accept whatever comfort Corrie could provide.

Earlier that day, Rube had made some crass comment about another couple of dykes in our midst, and only intervention from Imran had prevented Corrie from attacking the bastard.

“I’m talking irony, right?” Imran said. The thin Australian was sitting cross-legged in the forest litter. He waved a hand, indicating the lush vegetation. “We got our own Amazonia here, I’ve never been anywhere so full of life as this. And–”

“Water, water everywhere, but fuck all to drink,” croaked Corrie.

Imran looked puzzled, didn’t get the reference. “Nothing to eat,” he went on. “All this, and nothing to eat.”

Corrie nodded. Imran was okay, if a little too earnest and literal-minded at times. What he said was true.

Corrie could just about manage to keep down a few nibbled fragments from some of the plants and coralline plaques, but any more and she’d vomit until she felt as if she was turning herself inside out. Something to do with the complex oils packed into the cells of just about every living thing in the jungle. Some of the others had even worse reactions if they tried to eat. Rachel, as if her grief was not burden enough, had found it impossible to keep down so much as a mouthful.