Panic in Level 4: Cannibals, Killer Viruses, and Other Journeys to the Edge of Science (15 page)

Read Panic in Level 4: Cannibals, Killer Viruses, and Other Journeys to the Edge of Science Online

Authors: Richard Preston

Tags: #Richard Preston

Great Smoky Mountains National Park is the most-visited national park in the United States. More than nine million people pass through the park and experience its sights each year—that’s more than twice the number of people who visit Grand Canyon National Park annually. Now the primeval rain-forest habitats of the Great Smoky national park were under grave threat. In 2003, Kristine Johnson asked for and got about $40,000 from the Forest Service to save the hemlocks in the Great Smoky Mountains park. In the next few years, the Forest Service spent about $15 million on research into ways to control the adelgid, but it spent very little to actually deploy the weapons that were available. By 2007, direct Forest Service funding for the park to fight the bugs was only $250,000 a year, with private donations increasing the total somewhat.

“The government is so damned slow,” Blozan said. “Very little was done in the first two to three years.”

Then, just as the insects appeared in the Great Smokies, Charles Taylor, a Republican North Carolina congressman who was the chairman of the appropriations subcommittee in charge of the national parks, began seeking $600 million from Congress to build a highway across Great Smoky Mountains National Park. The park was next to Congressman Taylor’s district. Because the terrain in the Great Smokies was so rugged, the road would need to include three bridges, each likely to be longer than the Brooklyn Bridge—pork spanning a wilderness. Congressman Taylor argued that local residents would need to use the road and that it would bring jobs to his district. Environmentalists called it “the road to nowhere.” The road went places in Congress, which appropriated $16 million to develop plans for it. This slug of funding tended to squeeze out other congressional appropriations for Great Smoky Mountains National Park. And none of the road money could be used for controlling the insects. In 1988, when Yellowstone National Park was devastated by forest fires, the federal government spent more than $100 million trying to put the fires out.

At any rate, the staff of Great Smoky Mountains National Park did what they could with the money they had. In 2003 and 2004, park employees treated hemlocks near public areas with imidacloprid—trees in campgrounds and along roads but not those deeper in the woods. The next year, the chemical was approved by the EPA for use in forests, and Kris Johnson and her colleagues designated special zones, called “hemlock conservation areas,” where every hemlock would be treated. Will Blozan’s company, Appalachian Arborists, won a contract and put a crew of five to work, while another crew, of eight, went to work under a park forester named Tom Remaley. The conservation areas totaled two square miles; Great Smoky park covers eight hundred square miles.

The biggest problem was carrying the water needed to mix with the chemical. The crews collected water from creeks in jugs, put the jugs in backpacks, and rhodo-wrestled their way up the mountainsides. A crew could treat between a hundred and four hundred hemlocks a day. At that pace, saving all the hemlocks in the national park was simply not possible. (Bayer later came up with a sort of a pill containing imidacloprid that could be tucked among the roots of a hemlock. The pill doesn’t require water. As this is being written, the pill is being tested. If it works, crews carrying backpacks full of pills might be able to treat thousands of hemlock trees a day.)

In no other park were officials making the kind of effort that Great Smoky officials were. “Many other parks are ‘monitoring the decline,’ as I would put it, while they’re implementing control in high-public-use areas,” Johnson said. “I could put a hundred people to work treating hemlocks.”

The woolly adelgid had not yet arrived in Cook Forest State Park, in northwestern Pennsylvania, which contained some of the richest old-growth eastern hemlock forest. “These parks should have a plan ready, and at the first sign of adelgids they should execute their plan,” James Åkerson, the Shenandoah ecologist, said. A few million dollars—and a pill that works—would probably save the remaining fragments of old-growth hemlock forests. It wasn’t clear that the government cared to spend the money, though.

While the parks were waiting for Washington, Appalachian Arborists was hired to treat hemlocks on private property using the soil-injection method. The Reverend Billy Graham had thousands of sick hemlocks at his religious training center near Black Mountain, North Carolina; Will Blozan saved them. “If you don’t treat the tree, it will die,” Blozan said, “and then you’ll have to spend two or three thousand dollars having it removed.” He also began treating another species, the Carolina hemlock. A very rare tree, the Carolina hemlock occupies a narrow range, primarily in North and South Carolina, where it grows on dry, rocky outcrops, on the lips of gorges and clinging to cliffs. There were thought to be about 520 Carolina hemlocks in South Carolina. At last count, there were exactly twelve of them known to be in Georgia. The Carolina hemlock looks like something out of a Chinese painting. It’s a gnarled, wind-blasted thing with a mushroom-shaped top and downsweeping limbs flowing into space. Some of the smaller ones can be half a thousand years old. “The Carolina hemlocks are almost-beyond-words beautiful,” Blozan said.

The state of South Carolina hired Blozan and his partners to try to save the state’s 520 Carolina hemlocks, and the men treated nearly every specimen, often while rappelling down a cliff. Most of the Carolina hemlocks across the border in North Carolina were on national forest land, however, and were not being treated.

O

NE DAY IN

A

UGUST

, I drove into the Cataloochee Valley with Will Blozan to see what had happened. In the back of his jeep were backpacks full of ropes and tree-climbing gear. We followed a dirt road that switchbacked down into the valley. It was a lush place, lined with meadows at the bottom, rising into ridges and coves blanketed with forest. The forest was streaked with gray areas, as if smoke filled it. We parked in a meadow and put on our packs. It was a hot day, and clouds were piling over the mountains. Blozan looked around. “The truth is, I despise hiking,” he said. “I don’t do it unless there’s a tree to climb somewhere on the hike.” He wrapped a green bandanna around his head. We followed a trail that led into the woods along a creek called Rough Fork, crossing bridges made of single logs.

Big hemlocks, hundreds of years old, appeared. Sunlight seemed to blister its way through them. They were between 50 and 80 percent defoliated, but the national park crews had treated them, and many seemed to be alive, for now. “That one’s looking better,” Blozan noted, squinting at a hemlock that seemed half dead to me. He said that he had a map of the Cataloochee in his mind, with individual trees in it. “I’ve been all over these mountains. Even if I haven’t seen a tree in ten years, I still know exactly where to find it in a crowd of trees,” he said. “I’ve often wondered what a proctologist who’s passionate about his work thinks when he sees a crowd of people.”

He cut away from the trail, and we began bushwhacking up a slope. Here the trees were small, and patches of grass grew among them: the slope had been a cow pasture eighty years earlier. The slope ended on the knee of a ridge covered with rhododendrons. We followed the ridge upward, climbing steadily higher.

The trees got very big, and the forest seemed to get a lot darker. We had passed the edge of the old pasture and entered something like virgin American forest, a stretch of woods that had apparently never been logged. There were massive hardwoods—big yellow poplars, hickory trees, ash trees, mixed with an occasional sick-looking or dead hemlock. The ground was covered with all sorts of plants and shrubs—very high biodiversity, and the plants were all natives. No invading plants here. In various places there were woodland violets, early yellow violets, partridgeberry, masses of doghobble, wild lettuce, a lily called twisted rosy stalk, doll’s-eyes, and Dutchman’s-pipe. There was a brownish plant called squawroot that lives on rotting vegetation; bears eat squawroot in early spring after they come out of hibernation, and it purges their digestive systems.

The invaders were tiny or invisible to the naked eye. We passed hard, blackened stalks of wood: the remains of flowering dogwoods that had died a decade earlier from the invading dogwood fungus. Here and there stood rotting beech trunks and dead standing hulks called snags. The beech trees had gone almost extinct in this part of the Cataloochee within the previous five years. One small beech tree was still alive, its bark dotted with flecks of white fungus. This was the European beech fungus spread by a European insect. The beech tree was still alive, but it was doomed, and it was the last of its kind visible in that part of the forest. Here and there lay huge, moundlike, rotting cylinders of wood: the fallen trunks of American chestnuts, which had most likely died during the 1930s and ’40s, killed by the chestnut blight fungus, which drifted through in the air. Seventy years after dying, they still hadn’t rotted away. The forest was a palimpsest, telling stories of loss and change.

As we went along, I found myself rhodo-wrestling. The rhododendrons won, and Blozan moved ahead. He seemed to slip through them without much effort.

Higher up, we crossed the ridge and looked down into a cove. It was drained by a creek named Jim Branch. As we moved downslope into the cove, sunlight began to flood the area, and the air grew hot and ovenlike. Around and above us extended ghosts, hemlocks that had been treated too late and were dead or mostly beyond saving. The ground was covered with surging plants, coming up in the light, including masses of stinging nettles. I couldn’t see any adelgids; the parasites had died with their host. The air was filled with clouds of gray branches, like giant floating dust bunnies.

We stopped under a tall hemlock that glowed with green, a survivor in the cove. “This may be the healthiest hemlock in the park,” Blozan said. It was known as Jim Branch No. 10, and it was 150 feet tall. One of the ten experimental trees that the park had treated in 2003, it had been treated again in 2005.

Blozan pulled the end of a climbing rope out of his pack and tied it to a cord he’d left strung in the tree. He used the cord to pull the rope into the tree, and he anchored the rope, making it safe for climbing. When you climb a tree, you begin by climbing up a rope into the crown of the tree. This is because most trees don’t have branches near the ground that can be climbed on. The hemlock’s lowest branch was about sixty feet above the ground.

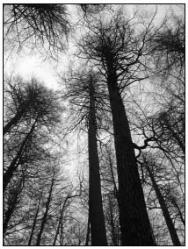

Hemlock skeletons. Old-growth eastern hemlocks in the Cataloochee Valley killed by the hemlock woolly adelgid.

Will Blozan

Blozan put on a helmet and a tree-climbing harness and began ascending along the rope, using rope ascenders—mechanical devices that grab a rope and enable a person to climb up the rope without slipping down it.

I put on my helmet and harness and waited, watching Blozan. He got into the branches and kept moving upward until I could barely see him. Then I started ascending the rope, using ascenders.

Sixty feet above the ground, with Blozan climbing above me, I stopped and stood on a branch. (I was still attached to the rope, so that I couldn’t fall.) Then I opened a bag and took out a complicated rig of ropes called a motion lanyard. The motion lanyard, also called a double-ended lanyard or a spider lanyard, is the principal tool used by some climbers for ascending to the tops of extremely tall trees, including hemlocks and redwoods. Here I will call it the spider lanyard.

The spider lanyard works much like Spider-Man’s silk. You dangle in the air from the spider lanyard, which is attached to branches over your head. While your weight is suspended on the lanyard, you move upward by flinging alternating ends of it over branches overhead, getting it attached to successively higher branches. With a certain technique, using certain sliding knots, you can raise your body upward through the air, suspended on the rope, without touching the tree, or you can lower yourself, or you can hang motionless in midair on the spider lanyard, with your feet and hands touching nothing. More often, though, you hang on it with your feet lightly braced against the tree, for balance. Your life depends on the spider lanyard. If it is incorrectly attached, it can fail or a branch can break, and you will fall to the ground. A skilled tree climber can move from point to point in a tree while suspended entirely on ropes, not touching the tree with any part of his or her body.

Blozan was climbing rapidly above me, moving from branch to branch.

The tree was filled with a spicy tang, the scent of green hemlock, and it was covered with living things. There were rare dark-brown lichens called cyanolichens, which fix nitrogen straight from the air. They fertilize the canopy of old forests. There were beard lichens, horn lichens, shield lichens, and one called ragbag, which looks like rags in a bag. There were small hummocks of aerial moss, spiderwebs, insects associated with hemlock habitat. There were mites, living in patches of moss and soil on the tree, many of which had probably never been classified by biologists. The hemlock forest consists in large part of an aerial region that remains a mystery, even as it is being swept into oblivion by Mrs. Dooley’s bug.