Panic in Level 4: Cannibals, Killer Viruses, and Other Journeys to the Edge of Science (14 page)

Read Panic in Level 4: Cannibals, Killer Viruses, and Other Journeys to the Edge of Science Online

Authors: Richard Preston

Tags: #Richard Preston

Another example of an invasive species is the Ebola virus. Ebola is a parasite with a known tendency to make trans-species jumps into new hosts. Ebola lives naturally in some unknown type of host in central Africa—possibly a bat, possibly a wingless fly that lives on a bat, or quite possibly some other creature. Ebola probably doesn’t make its natural host very sick. Ebola makes primates incredibly sick. This means that primates are

not

the original host of Ebola.

Outbreaks of Ebola in humans tend to burn out fairly quickly, but Ebola is a far more serious matter for gorillas. In recent years, roughly a third of the gorillas in protected areas in central and west Africa have died from Ebola virus. The virus is spreading unchecked in the gorilla population of central and western Africa, and it kills around 90 percent of the gorillas it infects. No one knows how Ebola has been getting into gorillas; possibly some disturbance in the ecosystem has put the animals into contact with the unknown host of Ebola.

I sometimes wonder if the unknown natural host of Ebola is itself an invasive species—some sort of rodent or insect, perhaps—that’s moving into disturbed habitats in the African rain forest. If so, this might explain why Ebola seems to be jumping into gorillas more frequently these days. Ebola’s host might be moving into new niches that have opened up in a rain forest that’s being changed by logging and human invasion. The Ebola host might be bringing itself and its parasite—Ebola—into close contact with gorillas. The World Conservation Union recently put the western gorilla on its critically endangered list; the Ebola virus, together with poaching, could push the western gorilla to extinction in the wild (some gorillas would persist in captivity). In other words, what happened to the American chestnut could also happen to the western gorilla: functional extinction due to a species-jumping parasite.

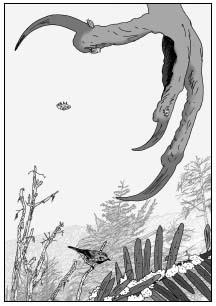

Hemlock woolly adelgid crawlers.

Artwork by Peter Arkle

Global climate change has become entangled with the problem of invasive species. A warmer climate could allow some invaders to spread farther, while causing native organisms to go extinct in their traditional habitats and making room for invaders. The earth’s biosphere can be thought of as a sort of palace. The continents are rooms in the palace; islands are smaller rooms. Each room has its own decor and unique inhabitants; many of the rooms have been sealed off for millions of years. Now the doors in the palace have been flung open, and the walls are coming down.

Global climate change may be helping the hemlock adelgids spread both north and south. Winters in the north are becoming steadily warmer, and the insects are not likely to be hit as often with deep cold. Summers in the southern Appalachians have lately become drier and hotter, and drought stress makes infested hemlocks far more susceptible to parasites. Climate change may also mean that the adelgids will be more active when birds are flying south. Recently, the woolly adelgid has turned up in Ohio, Michigan, Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine—approaching the northern limits of the hemlock range. Wherever it goes, it seems to get into every hemlock. It kills saplings before they can produce seeds, and so, in every place it arrives, it stops the hemlock species from reproducing. Many experts have concluded that the insect could kill nearly all the eastern hemlocks; if so, the species would essentially disappear from the wild.

O

N

D

ECEMBER

3, 2001, an arborist named Will Blozan discovered woolly adelgids on the branches of a wild hemlock in the Ellicott Rock Wilderness, on the Blue Ridge in South Carolina, near the extreme southern end of the hemlock range. No one had expected to see the insect this far south so soon. “It was a spear through the heart,” Blozan told me. He phoned Rusty Rhea, an entomologist and the forest-health specialist for the Forest Service in Asheville, North Carolina. Rhea was surprised. He sent out a bulletin to all rangers in the area warning them to look for adelgids. Within two weeks, Rhea was getting reports. The insect had gone all over the mountains.

Will Blozan is a tall man in his thirties with dark blue eyes that can take on a guarded look, and he has a laconic way of speaking. Blozan has wide shoulders and powerful-looking hands, but his hands move with a sensitive, precise quality—they’re the hands of a professional tree climber. He is the co-owner of a tree-care company called Appalachian Arborists, based in Asheville. (Arborists, who used to be known as tree surgeons, get around in trees using ropes.) He is also the president of the Eastern Native Tree Society, a small organization dedicated to discovering giant trees in the East. Since 1993, he had been spending his spare time exploring patches of old-growth forest in the Appalachians from New Hampshire to Georgia. Will Blozan became well known among tree biologists for having discovered and measured many of the tallest and largest trees in eastern North America. He often found them while he was bushwhacking through remote valleys in the southern Appalachians; he got into places that may not have had human visitors in years or decades.

In the Great Smokies in summer, the heat can be Amazonian. The land can slope sixty degrees, and in many places the undergrowth consists of a mesh of rhododendrons. “It’s total suckage in there,” Blozan said. “‘Rhodo wrestling’ may be the appropriate term for movement in the Smokies.”

When he found a big tree, he would get an estimate of its height using a laser device. Later, he would climb to the top, using ropes, and would send a measuring tape down along the trunk—this is the only way to determine the height of a tree to the nearest inch.

As he explored around, measuring tall trees, Blozan spent a lot of time around the southeastern tip of Great Smoky Mountains National Park, in a place called the Cataloochee Valley. It is a rain-forest wilderness, “well known for making you wet,” Blozan said. The Cataloochee Valley is centered on a rumpled drainage dissected by hundreds of small upland coves and divided by ridges and mountains. A few hiking trails wander through the Cataloochee, but many parts of it are very difficult to enter.

Blozan eventually discovered that the Cataloochee Valley has the highest average tree height—more than 160 feet—of any watershed in eastern North America. The Cataloochee contains more than 80 percent of the world’s tallest eastern hemlocks. It also contains the world’s largest yellow poplar and four of the world’s tallest white pines, including the tallest tree in eastern North America, a white pine that Blozan discovered in 1995 and named the Boogerman Pine. In January 2007, he found what turned out to be the world’s tallest eastern hemlock, growing in a cove in the Cataloochee. He and Jason Childs, another arborist, climbed it and measured it with a tape, and got 173.1 feet. Blozan named the world’s tallest hemlock Usis, which is the Cherokee word for “antler.” “The Cataloochee is the epicenter of the eastern hemlock species,” Blozan said. “The valley has the largest and best groves of eastern hemlock in the world.” In effect, the Cataloochee Valley is the Notre Dame cathedral of the eastern forests.

By the summer of 2002, the woolly adelgid had been found in the Cataloochee. Few national parks have a forester on the staff, but the Great Smoky park does: Kristine Johnson. Kris Johnson is a slender woman in her fifties with a calm manner. Since 1990, she has been managing the park’s efforts to beat back exotic invaders. “We currently have about a thousand sites in the park where exotic plants have gotten in, and we’re dealing with ninety different species of invading organisms,” Johnson told me—everything from Japanese stiltgrass to princess trees and fire ants. “We knew that sooner or later we would have the woolly adelgid. People around here have a saying: ‘All the trouble comes from the North.’ But we were still surprised by how quickly it got here.”

The parasite may have been carried to North Carolina by people. In the summer of 2001, state nursery inspectors began finding infested hemlocks in nurseries in western North Carolina. The contaminated hemlocks had been imported into the state from areas where the bug was a problem. North Carolina inspectors ordered the nurseries to destroy their infested hemlocks. This was a money-losing deal for a business. “A speculation is that less-than-scrupulous nursery owners were unloading infested material on their customers,” Kris Johnson said.

Now that the insect had arrived in the Great Smokies, what weapons were available to combat it? And how many hemlocks would need to be defended? It was clear that large numbers of hemlocks grew in Great Smoky Mountains National Park, but it wasn’t immediately obvious, even to Kris Johnson, roughly how

many

there might be. She and her colleagues estimated, finally, that there might be 300,000 to 400,000 large hemlocks in the national park, not counting smaller, younger trees. Most of the hemlocks were tucked away in wilderness valleys, far from roads or trails.

Oil spray—the treatment that helps smaller trees in urban yards—wouldn’t work in wilderness areas, where hundreds of thousands of large hemlocks would need to be drenched every year. There were two other promising options, though. Scientists at the University of Tennessee, funded in part by a private group, Friends of the Smokies, started a small lab for breeding a kind of lady beetle native to Japan that eats woolly adelgids. It was hoped that the beetles, released into the wild, would eat lots of adelgids, cutting down their numbers and eventually getting their population reduced to the point where hemlocks could survive the infestation.

Rusty Rhea, of the Forest Service, pushed the beetle strategy forward, and researchers began releasing the beetles. The lady beetles were tiny—the size of a sesame seed—and they initially cost about two and half dollars each; a cup of them cost thousands of dollars. When they were released at test sites, they had no measurable effect. But in 2007 (after years of test releases), a test in Banner Elk, North Carolina, in which different species of adelgid-eating beetles had been released over several years, had promising results. One type of beetle, from the Pacific Northwest, got established at the site and was eating adelgids, and the hemlocks there were looking better. Even so, there remained questions about whether and how quickly such results could be achieved on a large scale—if enough beetles could be bred and released and would multiply fast enough to save the hemlock forests that were dying or were under immediate threat. The beetles might work in the long run, but by then it might be too late for most hemlocks.

There was also an insecticide treatment, a chemical called imidacloprid, which is made by Bayer. Imidacloprid had to be mixed with water and injected into the soil around the root system of a hemlock. The chemical slowly moved into the foliage. When the adelgids sucked it into their bodies, they died. Imidacloprid is an artificial kind of nicotine. (Tobacco plants produce nicotine as a natural insecticide.) The injections were labor-intensive, but there was no good alternative: if imidacloprid was sprayed from the air, it would wipe out beneficial insects and wouldn’t kill many adelgids—the insect’s woolly coat sheds water.

The chemical had some advantages: it didn’t migrate much through soil, so it would not be likely to spread widely into the environment, and it degraded quickly in sunlight. However, it was a toxic compound that could kill many grubs in the soil near the tree, as well as other insects feeding on the tree. It did not seem to affect vertebrates—frogs, salamanders, birds.

“I wouldn’t want to see chemical treatment be the only way to save hemlocks, but nothing else is ready right now,” Blozan said. “Either you get some invertebrate kill around the treatment site or you get an ecosystem collapse—that’s the choice.”

As soon as adelgids were found in the park, the Forest Service and Bayer began seeking Environmental Protection Agency permission to use the chemical in wild forests (it had already been approved for ornamental and landscape settings). The park treated ten old-growth hemlocks, as a test. Will Blozan’s company, Appalachian Arborists, was hired to climb the trees and take samples of the foliage, to see how the chemical was moving through the tree. It can take a year or two for the benefits to become noticeable; some trees die anyway. “After treatment, the hemlock can look completely dead, but sometimes it will come back, and in three years it’ll be vigorous,” Blozan said. The ones that lived would need to be retreated every few years. The hemlocks would be like AIDS patients: they would never be free of the disease, though some might survive indefinitely on drugs. “What you get is a forest on life support,” Blozan said. “But at least it can be kept alive while we hope for a cure.”

Getting funding to fight the insect in the Great Smoky Mountains park was a byzantine process. The National Park Service, Kristine Johnson’s employer, ran the park, but the Forest Service had responsibility for controlling pests in federal forests, including the national parks. The Forest Service is in the Department of Agriculture, while the National Park Service is in the Department of the Interior. Funding for insect control competes with other Forest Service needs, such as fighting forest fires. And the Forest Service appears to concentrate its pest-control efforts on trees that have commercial value—it had spent more than $100 million trying to get the emerald ash borer contained—and hemlocks aren’t worth money.