Owls Aren't Wise and Bats Aren't Blind (26 page)

Incidentally, the original of “Pop Goes the Weasel,” quite different from the version that I grew up with, was written by the nineteenth-century English poet W. R. Mandale:

Up and down the City Road,

In and out the Eagle,

That’s the way the money goes—

Pop goes the Weasel.

As already noted, many predators feed on weasels. However, domestic cats seldom seem to eat weasels which they’ve killed. On at least three occasions I found weasels in their ermine coats lying dead on our barn floor. Obviously killed by one of our cats, they had no marks on them except a bite in the neck. My suspicion is that the weasels’ strong scent, so characteristic of their family, caused the well-fed cats to turn up their fussy feline noses at such fare. Wild predators, of course, can’t often afford to be so fastidious!

Although they are victims of a great deal of bad publicity, much can be said in behalf of weasels. They’re an important means of controlling mice, rats, and other small rodents, and this more than compensates for their occasional raids on poultry. Indeed, although weasels certainly do kill poultry on occasion, much of the killing blamed on them has been perpetrated by rats, an occasional mink, and other predators.

THE MARTEN

Although weasels can climb trees, they are primarily ground-dwelling predators. Fishers are agile tree climbers and readily ascend after porcupines and squirrels, but they, too, are primarily terrestrial. The smaller, lighter marten

(Martes americana),

however, is capable of exploiting the treetops more fully than the fisher.

Martens are about two feet long, including the tail, and usually weigh either side of two pounds. This light weight enables them to pursue the little red squirrel through the treetops on branches far too small to bear the weight of the much larger fisher. Thus, although it spends the majority of its time on the ground—where, after all, the majority of its larder is found—the marten can be considered semiarboreal.

No doubt the sight of martens zipping through the treetops in pursuit of red squirrels has given rise to the idea that they subsist mainly on a diet of squirrels. The marten, however, like the fisher, eats what it can readily catch or find. Mice, voles, and chipmunks make up much of the marten’s diet, but birds and birds’ eggs, hares, grouse, large insects, fruit, nuts, and carrion are all fare for this versatile predator.

With its yellowish-brown fur, a muzzle longer and more pointed than the fisher’s, and larger, more pointed ears, the marten’s face looks almost fox-like. And like the weasel, the marten can have its engaging side, too.

My good friend Tim Jones saw this facet of marten personality in an encounter in Maine some years ago. He had shot a buck about a mile from his car. After field-dressing the deer, he carried his pack, rifle, and heavy jacket out to his car. When he returned and began to drag the deer toward the car, a pair of martens suddenly emerged from inside the carcass.

Sometimes coming within a foot of Tim, the pair alternately tugged at the deer and chirred and chittered anxiously in high-pitched voices not unlike that of a red squirrel. According to Tim, their whole demeanor clearly said, “Chitterchitter! My deer! My deer!” The pair persisted and followed for some distance before finally turning back to content themselves with the leavings.

When he returned a second time for the deer’s heart and liver, the martens were even more perturbed. In high dudgeon, they squeaked, chirred, and chittered their alarm and displeasure at seeing their food supply further diminished: “Chirr, chirr, chitter, chitter! My gut pile! My gut pile!” Tim was utterly charmed and captivated by the whole episode.

Our North American marten is commonly called the pine marten, but this is a misnomer. The true pine marten

(Martes martes)

is native to Europe. As with other New World creatures, European settlers evidently named our marten after a similar European relative with which they were familiar.

Martens are very much creatures of coniferous forests, or of mixed forests with a strong coniferous component. It’s not surprising, therefore, that their range is primarily in Canada and Alaska. In the United States, they’re found only in northern New England, the northern tip of the Great Lakes states, the Rocky Mountains, and a strip down the Pacific coast.

Like fishers, martens usually den in tree cavities, though a hollow log will also serve. In typical weasel fashion, they reap the benefits of delayed implantation. Usually three or four kits are born in April or May; though tiny and premature, they’re covered with fine, yellowish fur.

A close relative of the famed sable

(Martes zibellina)

of northern Europe and Asia, the marten is a much-prized furbearer. Eliminated from some portions of its former range by the land clearing and unregulated trapping of bygone years, this interesting weasel cousin is now being restored to its old haunts.

THE MINK

Curiously, and uncharacteristically for most members of the weasel family, little in the way of folk myths and erroneous beliefs seem to have sprung up concerning the mink

(Mustela vison).

Why this is so is anyone’s guess. Although infrequently seen, even in rural areas, the mink is widespread and common. Its range encompasses all of North America save Mexico, the Southwestern United States, and the Arctic reaches of Canada.

Mink are almost the same size as marten, though they are very slightly shorter and heavier. The differences make sense: the marten’s light weight enables it to leap along slender branches, while the mink’s body, just a bit stockier, works well for one who spends much of its time in the water. Considered semiaquatic, mink function well in an aquatic environment, although they lack the adaptations of their big cousins, the otters (see below). Good swimmers, mink lack the necessary lung power for sustained dives, and usually are submerged for only five to twenty seconds. Moreover, the mink’s eyes are incompletely adapted for underwater vision. Consequently, mink spend much of their time foraging along the edges of streams and marshes, both in and out of the shallows, rather than diving after fish.

Frogs, salamanders, crayfish, and other aquatic creatures make up a good share of a mink’s diet, with an occasional fish thrown in for good measure. Muskrats are also a favorite prey of mink, which follow them into their houses or burrows and there dispatch their hapless victims. In addition, mink prey on baby ducklings whenever possible.

Although mink are at home in and under the water, they also spend much time hunting on land. Mice, voles, rabbits, birds, eggs, and similar fare are all dinner for the mink while on land. Poultry also suffer occasional depredation by mink, and more than one hen-coop massacre blamed on weasels can be laid at the door of its semiaquatic cousin! Like weasels, mink engage in surplus killing and cache food; they also emulate weasels in trailing by scent.

Despite their wide range, relative abundance, and considerable time spent traveling about on land, mink are seldom seen. This is because they are primarily, though not completely, nocturnal.

Although mink are usually found near water, they’re by no means wedded to it. Last winter I happened to glance out one of our windows and was surprised to see a mink running along the edge of our woods. We live a good quarter-mile from water, and the mink was headed in a direction where no appreciable water can be found for at least another mile. This seemed to trouble the mink not at all as it unconcernedly bounded on its way through the woods.

On another December day in a snowy forest, I found the typical two-step tracks of what I at first assumed was a weasel. On closer inspection, however, the tracks seemed too large for a weasel. Although the tracks came from an area where there was no water for a long distance, I became suspicious. Sure enough, the tracks eventually led to a small brook, mostly frozen over after a spell of very cold weather. There the tracks ended at a hole in the ice, about the diameter of a golf ball, its perimeter slightly discolored and worn smooth by the track-maker’s repeated use.

Although mink raised on fur farms come in various mutant designer shades, wild mink sport a rich, brown pelage, except for a white chin patch. Their dense coat of underfur is covered by the long, dark guard hairs which give them their sleek, glossy appearance. Despite the availability of ranch mink, wild mink remain highly prized in the fur trade; evidently nature can still do a better job than humans of equipping mink with a dense, glossy coat.

Like all of the mustelids, mink deposit scent from their anal glands. However, the mink’s scent is particularly strong and unpleasant; many would rate it worse than the odor of skunk, although the mink can’t spray its scent as a defensive measure.

Mink breed during a period of over two months, starting in February. Implantation of the fertilized eggs is delayed for about a month; then a pregnancy of roughly twenty to forty days ensues. The young—typically three or four—are born, blind and covered with fine hair, in a hollow log, an expropriated muskrat house, or a burrow or cave in the bank.

THE RIVER OTTER

If many members of the weasel clan are viewed by some with loathing and disdain, the river otter

(Lutra canadensis)

manages to salvage the family honor. Whether in the wild or in a zoo or animal park, it seems that everyone loves otters! The reasons aren’t difficult to ascertain. With its bewhiskered visage, comically turned-down mouth, and often playful nature, the otter seems downright appealing to humans.

Aside from these attractive qualities, the otter is worthy of attention because of the way in which it has mastered its mostly watery habitat. Flawlessly equipped for this role, otters are a superb example of evolutionary engineering. The mink functions quite well in and under the water, but the otter simply revels in it.

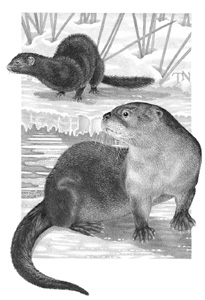

Mink

(top)

; river otter

Otters are the closest thing to seals that freshwater provides. Propelled by wide webbed feet, the otter is magnificently constructed for gliding easily through the water. Its fur is short and sleek, its body long and cylindrical; even its long tail, thick at the base but tapering to a pointed tip, seems almost like an extension of its streamlined body, rather than an appendage. Moreover, its eyes are well suited for underwater vision, and it has the lung capacity to remain submerged for several minutes at a stretch.

Anyone fortunate enough to observe otters in the water for any length of time can readily see how at ease they are there. With the utmost insouciance, they roll, dive, play, and generally disport themselves with little apparent effort. Thus otters can accurately be termed “heavily aquatic.”

Otters feed primarily on a variety of aquatic prey, particularly fish. For that reason they are sometimes blamed for killing large numbers of trout and other valuable game fish. This is generally quite unjust. Except for special circumstances (a small, stocked trout pond, for instance), otters, like any predator, will usually kill the easiest prey that requires the least expenditure of energy. That often means so-called “rough fish”—suckers, dace, and the like—rather than swift, wary game fish.

Several years ago my older son and I were offered a rare treat—a graphic example of the otter’s liking for fish. We were canoeing down a broad, slow stretch of a stream appropriately named Otter Creek. As we approached a huge elm tree that had fallen into the water, we suddenly saw movement ahead of us. My son was in the bow, and he whispered, “Otters!”

Sure enough, there were two otters, rolling and diving around the skeleton of the old elm tree. We quietly shipped our paddles and drifted nearer, when suddenly one of the otters, with a sizable fish in its mouth, clambered up onto the trunk of the elm. There it proceeded to devour the fish at leisure, and we were so close that we could even hear it crunch up the bones!

Anthropomorphism—attributing human thoughts and emotions to animals—is an easy trap to fall into; animals aren’t human and don’t think and react as we do, however much we sometimes like to think so. It’s extremely difficult, however, to put any construction other than sheer playfulness on some otter activities, notably sliding.

When otters climb steep banks and toboggan down a muddy, slippery slide into the water, time after time, there appears to be no biological imperative behind it; it just seems to be a pleasurable activity. Likewise, otters traveling in snow will fold their front legs back along their sides, push off with their hind feet, and glide down the slightest slope wherever possible—and sometimes even push and slide on a level. Whether sliding down a bank or gliding on the snow, the hind legs trail behind the body after giving an initial push.

Because otters spend so much time in the water, and are mostly seen in or along the edges of it, most people think they’re almost completely tied to water. When the spirit moves them, however, otters can be notable overland travelers, traversing several miles of dry land before reaching another body of water. In the process, they are adept at finding small mammals and birds, insects, and similar terrestrial food.