Owls Aren't Wise and Bats Aren't Blind (24 page)

The skunk is a polecat.

The skunk is a polecat.

Badgers are rather placid and benign.

Badgers are rather placid and benign.

The wolverine is virtually the devil incarnate.

The wolverine is virtually the devil incarnate.

Oil spills have killed most sea otters in Alaska.

Oil spills have killed most sea otters in Alaska.

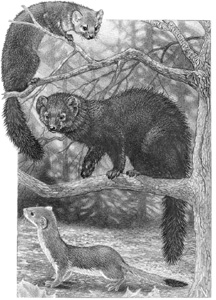

THE STOREKEEPER ASKED ME WHAT SORT OF ANIMAL HE HAD SEEN BOUNDING ACROSS THE ROAD IN FRONT OF HIM: HIS DESCRIPTION WAS A PERFECT MATCH

American marten

;

fisher

;

long-tailed weasel

FOR THE FISHER, BUT HE SHOOK HIS HEAD WHEN I TOLD HIM SO. “No,” he said, “it was nothing like a cat.” He was not an ignorant person, but he was the victim of a very common wildlife misunderstanding—that of the “fisher cat.”

Far from being a cat, the fisher is a midsized member of the weasel family, among the most diverse and extraordinary groups of mammals.

Known to scientists as mustelids—the name ultimately stems from Latin

mus,

mouse, possibly because weasels are preeminent mousers—this family has exploited an extremely wide range of ecological niches. Their extraordinary diversity has required major adaptations in form and function, with the result that some members of the weasel tribe bear scant resemblance to anything we might think of as weasels.

Despite these differences, weasel family members share at least three major traits in addition to the fact that they are all carnivores. For one thing, they all have anal scent glands that can emit very unpleasant odors. The skunk has made a fine art out of this attribute, converting it into a potent defensive weapon, but other family members have equally unpleasant scents, though they lack the skunk’s scent volume and efficient distribution system.

For another, most weasel family members utilize something known as

delayed implantation

in their reproductive cycles. This means that the fertilized egg doesn’t attach to the wall of the uterus and begin to grow until months after breeding, and only a relatively short time before birth. Delayed implantation offers some major advantages, which will be explored more fully in the section dealing with weasels proper.

A third characteristic of the weasel family is a common gait that results in what might be called the two-step. In this method of locomotion, the tracks of front and hind feet are superimposed. The result is a track that looks as if it were made by two feet rather than four, one slightly to the rear of the other. Although some weasel family members use other gaits as well, this one is so typical that anyone who follows mustelid tracks very far is almost certain to see this distinctive pattern.

With these shared traits in mind, let’s examine the unique qualities of the various weasel family members, for, despite the similarities, the differences between these creatures are striking. The weasel family is relatively old as mammals go; fossils of weasel ancestors at least 40 million years old have been found. In the immense interval since, evolution has worked its wonders. Form and function have become inseparable, so that the highly diverse shapes and sizes of the weasel clan are matched by the equally diverse ecological niches they occupy.

THE FISHER

As already noted, the name “fisher cat” is a widely used and wholly inappropriate name for the fisher

(Martes pennanti).

Although its glossy, dark brown outer fur looks almost black at a distance, and its tail is moderately bushy like that of some cats, it’s hard to fathom why this large, forest-dwelling weasel has been associated with the feline race. Although proportionally thicker in the body than the super-slender weasel, the fisher is nonetheless elongated, short-legged, and possessed of a pointed, weaselish snout that looks anything but catlike. Likewise, the fisher’s bounding gait hardly resembles that of a cat.

Even its correct name—fisher—is extremely misleading. Fishers certainly don’t pursue live fish, nor would they be apt to eat fish at all except through the lucky—and infrequent—circumstance of finding a dead one. Whence the name, then?

In Old French, the polecat or fitchew—a European weasel relative—was called

fissel,

later

fissau.

This was gradually transmuted in English to

fitcher

and

ficher.

Ultimately, the term

fitch

was applied to the ferret, which is a domesticated strain of the polecat. The reasonable assumption is that European settlers in North America applied the name

ficher

to the unfamiliar animal that bore a cousin’s resemblance to the familiar polecat. Incidentally, the Native American name of

pekan

or

pekane

is also used for the fisher on occasion.

As is the case with many other wild animals, the size of the fisher is often grossly overestimated. Far from being large, it is comparable in weight to a house cat, though longer. Like most others of the weasel tribe, fishers exhibit sexual dimorphism, which is the scientist’s fancy term for a major difference between the sexes. In this instance, it refers to the fact that males are much larger than females. Thus a huge male can weigh up to twenty pounds, but that’s unusual; adult males typically weigh ten or twelve pounds, females only five to seven.

The fisher is very much an animal of the northern forests. Most of its range is in Canada, though it is also found in the United States throughout most of northern New England, the northern Great Lakes region, the far northern Rocky Mountains, and parts of the Pacific Northwest.

Although the fisher eats a wide variety of food, its major claim to fame is as the only truly effective predator of the porcupine. How do fishers manage to kill porcupines with some degree of consistency when this feat mostly eludes much larger predators, including coyotes, wolves, cougars, and bobcats?

It’s widely believed that fishers kill porcupines by approaching them from the front, then flipping them on their backs and attacking their quill-less bellies. But on close examination, this notion makes little sense, because it requires fishers to perform the extremely difficult feat of overturning unwilling victims as much as five times their own weight.

Research has shown that fishers use a different and much more effective method of attack. Extremely quick and agile, they dart in and out, repeatedly biting the porcupine around its unprotected face while dodging the potent slaps of its quilly tail. Eventually the porky succumbs to numerous bites or becomes so disabled that the fisher actually can roll it over with impunity and attack the unprotected belly.

The fisher’s excellent tree-climbing ability offers a second major advantage, for it enables the fisher to attack porcupines when they’re feeding or sunning themselves aloft. Despite these advantages, the majority of fisher attacks on porcupines fail because the porky protects its face in a den or a tree hollow, or between its paws.

The fisher’s well-earned reputation as a porcupine killer has led some to the notion that fishers are immune to harm from quills. This is decidedly untrue: fishers are very good at avoiding quills, but occasionally one makes a mistake and gets a faceful. At best this is extremely painful, and at worst occasionally fatal.

Despite their fondness for fresh porcupine, fishers dine on a wide variety of food. Mice, voles, squirrels, chipmunks, and similar small creatures make up a major part of their diet, supplemented by grouse, hares, and the carrion of larger animals, such as deer. And despite being carnivores, fishers also consume a surprising amount of apples, berries, other fruit, and nuts.

How important is the fisher in controlling porcupines? For decades the state of Vermont, where fishers had long been absent, suffered from a plague of porcupines. Dogs routinely encountered them and subsequently paid a painful visit to the local veterinarian for quill removal. As noted in chapter 5, the big rodents also gnawed on everything salty from human sweat, including tool handles and canoe paddles—even outhouse seats! And damage to valuable timber trees, caused by porcupines chewing off their bark near winter dens, was rampant—and costly.

The state paid a bounty on dead porcupines for many years, but, as is virtually always the case with bounties, this measure proved ineffective. So serious had the situation become that in the late 1950s the Department of Forests and Parks began a program of putting poisoned apples (shades of Snow White!) in porcupines’ winter dens.

Although the poisoning program was reasonably effective, Forests and Parks then began importing fishers live-trapped in Maine. These were released throughout the state, and within a few years the porcupine was back in a natural balance with its habitat.

Despite its success, this program was hardly noncontroversial. New in the experience of most Vermonters, the fisher engendered wildly exaggerated— even hysterical—fears. Some sportsmen blamed the fisher every time they failed to find grouse or snowshoe hares in their favorite covers, never mind that populations of these species are notably cyclical. Rumors of fishers weighing forty pounds and more were common. One person even phoned the Fish and Wildlife Department to report that a fisher had killed one of his heifers and then leaped over a fence with the heifer slung over its back—a feat beyond the prowess of even a full-grown cougar!

Letters to the editor warned of the dangers fishers posed to pets and small children. This was a gross exaggeration, to say the least. Although the fisher, like most predators, is an opportunist, and thus will certainly kill a house cat if it encounters one, it poses no threat to any but the very smallest dogs. As for attacking children, this is a ridiculous assertion; fishers simply do not attack humans, even very small children.