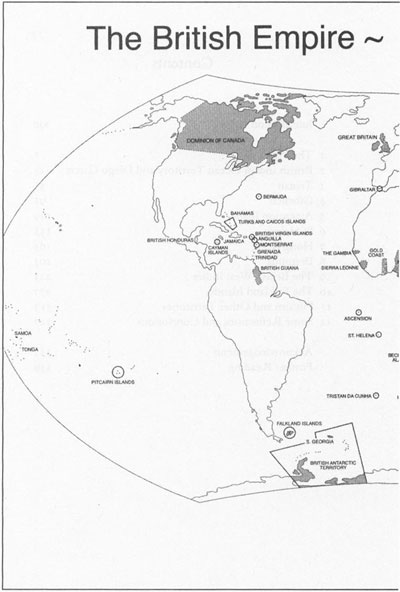

Outposts

Journeys to the Surviving Relics of the British Empire

For Elaine

1

The Plan

2

British Indian Ocean Territory and Diego Garcia

3

Tristan

4

Gibraltar

5

Ascension Island

6

St Helena

7

Hong Kong

8

Bermuda

9

The British West Indies

10

The Falkland Islands

11

Pitcairn and Other Territories

12

Some Reflections and Conclusions

The world has changed a very great deal since 1984, the year during which I wrote the following affectionate, in many ways rather poignant, and on occasion sentimental account of my wanderings to and around the British-run relics of the greatest of all modern Empires.

The small and curiously discrete world of which I was writing then has changed physically, of course. The tiny Imperial assemblage I was then able to describe has shrunk, at the very least by the removal of the territory of Hong Kong from the rolls. I stood in the hot rain that June night in 1997 and watched the Union flag come down, and as midnight struck and the Chinese victory fireworks started to erupt, so I watched as

Britannia

sailed away for London, taking with her the colony’s last Governor and his Prince, and a clutch of women standing at the taffrail, in tears. Even putting sentiment deliberately to one side, it would be idle to suggest that night was anything but unbearably moving.

The Imperial population, if we can still call it that, evaporated with that single and long-expected act of retrocession, from the full six million it was back then to just the few tens of thousands of people who remain under London’s weary supervision today. A gathering of distant places which still had some slight significance before that June night—when, quite literally, the sun did not set on the British Empire—was reduced at the stroke of a midnight bell to not much more than a fistful of dust.

The world beyond the relict Empire has changed profoundly, too. The titanic stand-off between what we liked to call the superpowers was, in 1984, soon and quite unexpectedly to be over; today only one such power remains, and the totalitarian ideology that underpinned the other, and which had such relevance to many of the tiny places in the world that were once run from London, has

now all but vanished. In 1984 a place like Ascension Island derived much of its reason for being from the Cold War; it was close enough to the malleable states of West Africa to make it the ideal location for electronic spies seeking to monitor the increasing threat of Marxism. With the fear of that ideology all but vanished, there now seems little point to the populated existence of the island (after all, the island was barely populated before we seized it) nor to Britain’s continuing possession of it.

Much else has changed besides. The public attitude towards Empire and to the very notion of Imperialism itself has undergone a swift metamorphosis over the past two decades. Post-colonial literature, already in 1984 a small but well-established genre, has since swollen to a flood, and has been joined by a canon of scholarly studies emphasising the point that, no matter how benevolent and well-intentioned the colonising powers may have thought themselves to be, their effect upon the world was ultimately to lead to the gravest of ills. Affection and poignancy are rarely to be found in today’s writings about a kind of governance that is now regarded as having been politically most incorrect; sentiment, never the best lens through which to view anything, is these days a wholly inadvisable means of looking at past Empires, which appear to deserve only the cold gaze of the post-structuralist sceptic.

There are a number of obvious reasons behind the burgeoning of these new ways of thinking about Empire. Perhaps the most important is the flourishing of journalism and literature on the subject by post-colonialist authors—the old guard like V. S. Naipaul, Chinua Achebe and Derek Walcott, and the more recent such as Salman Rushdie, J. M. Coetzee and Vikram Seth—whose experiences and memories of being part of the enginework of colonial subjection have found a wide and admiring audience. The fact that Naipaul is now a Nobel Prize winner underscores the wide admiration for his specific achievement in giving a voice to the Imperially ruled, rather than to the Imperially ruling, classes.

Then again, the rather more widely appropriated culture of repudiation, which lies at the heart of so much present-day art and literature, has enabled many to challenge the comfortable old

assumptions of white-run Empire simply because they are comfortable and old and white, and has elevated anti-colonialist sentiment to the status of high fashion. Edward Said, the noted and prolific Palestinian scholar at Columbia University, who wrote the groundbreaking 1978 work

Orientalism

and went on to publish

Culture and Imperialism

in 1993, has long been a standard-bearer for the new movement. Few are the students who do not regard his trenchant views of the cruel and crabbed legacies of colonialism as having the heft and authority of Holy Writ.

But there is one further reason, rather less easy to discern, behind the change.

There is currently an uncomfortable feeling abroad, a feeling that was not recognisable in 1984 and is still not fully recognised today, which in essence holds that an Empire of quite another sort—or some kind of phenomenon that we feel like calling an Empire—is stealthily and subtly returning to centre stage. We have an uneasy feeling that whatever this new entity is, it is before too long going to exert an unacceptable and undesirable influence over the world, and that the entire cycle which we thought had ended with the slow collapse of all the great sea-borne European Empires during the three decades following the Second World War—the British Empire pre-eminent among them—is in fact beginning all over again.

The phenomenon of which we have such grave suspicion has many names:

globalisation

is currently the most popular and thus the most familiar.

Informal Empire

is another—the notion that since the old, formal Empires are all now dead, since the systems of unelected Governors and Viceroys and District Commissioners have all passed away, what replaces them is an unstructured kind of imperium, with on the one hand a slew of new and similarly unelected rulers, which in this case are banks, corporations and brands, all operating without restriction in a new and economically borderless world, and on the other hand a vast and disparate body of subject peoples, who are in increasing numbers bound to make use of these banks, corporations and brands and are kept in thrall to them unwittingly, but firmly kept there nonetheless.

The benefits of globalisation are proclaimed vociferously by the banks and corporations who are its prime beneficiaries: economies of scale mean that consumer products become cheaper and more widely available; bureaucracy crumbles in the face of corporate-directed efficiency; access to goods and services is more widespread, more

democratic

, the standard of living everywhere improves—everyone floats higher on an ever-rising tide of global prosperity.

But the darker side of the phenomenon, less readily observable, is what worries many. That the world is becoming increasingly ordered by unelected and faceless figures in distant (and most commonly American) corporate headquarters, figures who are answerable only to the shareholders in the country which is their base of operations. That there are fewer and fewer controls on those global operators—for under whose law, exactly, do they operate?—to limit unscrupulous and inhumane behaviour. That the less powerful—the employee in a Third World nation, working under contract for some distant American company whose responsibility is limited by distance and by adroit corporate lawyers—can be oppressed and cheated and denied rights, without anyone to notice or complain. That indigenous businesses can so easily be forced under, unable to stand the competition from the corporate super-giants whose growing share of world trade seems unstoppable, and whose ruthlessness is glorified by managers, who see it as essential for success.

It is because of growing fears about such inequities and excesses that a new mood of anger has lately settled abroad. Violent protests are now breaking out, sporadically but very noticeably, at those various forums around the planet—Seattle, Genoa, London, Ottawa—at which the world’s leaders gather to discuss, or seem to the protestors to be discussing, the profitable benefits of globalisation. Men like Jose Bove in France win enormous public support—and yet suffer harsh official sanctions—for demonstrating against such very obvious and palpable evils as those of the McDonald’s Corporation. The ‘slow food movement’ has taken off in Italy, for much the same reason—a gathering sense of loathing and fear that the tastes of the Tuscan epicure, let us say, might one day become

deeply influenced by men in grey suits from the same McDonald’s headquarters in suburban Illinois.

And then again, Marxist academics like Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri (the authors of a seminal book in 2000 called, somewhat unimaginatively,

Empire

) are carving significant inroads into current university thinking—nudging thousands of highly motivated young students into believing that this new Imperial phenomenon, presenting itself in a variety of guises from the ubiquitous consumption of American fast food to the immense readership of cheap American magazines to the near-universal acceptance of American commercial practices, cannot but suggest the onset of a harmful tendency, one that is eventually just as certain to damage the entire world as the classic Empires did in their day.

This current ferment is an early sign of what may well become (at least, so most activists hope) a widespread movement of concern and hostility. It also hints at why so many are currently so hostile to the idea of all Empires that went before—because by recognising and demonising these past Empires, we can perhaps better warn ourselves of the perils of the new super-Empire that is readying itself to succeed them. It is not simply that V. S. Naipaul is an eloquent spokesman for the victims of past Imperial injustice; nor that the whim of fashion has at last reached the shores of Empire. It is that we sense something akin to the old evils lurking in the wings, and we want our arguments against them to be honed to a perfect sharpness, ready to do battle.

It is against this backdrop of an entirely new and fascinating intellectual movement, then, that the following stories from my languorous journeyings around the fifteen or so relics of the British Empire may perhaps be read anew. I confess that there is much affection in the tales that I then wrote; and I now have to accept that affection for such things is a sentiment quite thoroughly out of date, and most improper, and undeserved.

Or is it?

I mention above that a fear exists that the new Empire-in-the-making may be as harmful to the world as those that came before. But just how harmful were those previous Empires, in fact?

In principle, of course, they were a less-than-ideal arrangement—for how much greater an indignity could any people suffer than to have an alien power impose some form of rule upon them, often with racist overtones? How shocking for proud members of tribes in East Africa to be obliged to live under the Imperium of Berlin. How shaming for Madrassis and Bangaloreans to be forced to obey laws laid down by bureaucrats in London. Has there ever been a more humiliating period in Polynesian history than when the French came and told them where to work, how to behave and how it was permissible to dress? No—there can be no doubt that all such arrangements—whether the colonial masters came from Rome or Venice, were Ottomans or Mughals, had been educated at an École Supérieure or at Haileybury or the University of Tokyo—were misguided. The very idea of Empire is, by today’s standards and principles, quite wrong.

But setting principles aside, and accepting for a moment that these arrangements did hold, that these are realities of history which, like it or not, did take place—how truly dreadful were some or all of these arrangements?

And if one were to argue that not all were quite so frightful as the principle suggests they should have been, were some of these foreign Empires in fact

better

than others (or at least, less bad)? Did some few of them, perhaps, at least leave a legacy that was to be of some utility to those who had been colonised—a legacy that a dispassionate long view of history might argue offered some compensation for the shock, shame and humiliation of all those years under the Imperial heel?

It is at this point that I have to struggle to suppress a certain chauvinism which inevitably rears its head. For it seems to me today, after almost two further decades of hindsight and further wanderings and reflection on matters colonial, that of all the recent European sea-borne Empires—the French, the German, the Dutch, the Portuguese, the Spanish and the British—it is, singularly, the British Empire that managed to leave behind the kind of legacy of which, dare one say it, some might still be rightly proud.

Hong Kong, since 1997 once again a part of the China from which we wrested it by war in 1841, offers the most comprehensive examples of that legacy. There is a system of democracy in place, imperfect to be sure, and offered to the citizenry very late in the territory’s history, but which is somewhat more accountable than the cruel apparatus of government imposed by Beijing. There are courts that are, by and large, fair and impartial. Business contracts are exchanged and honoured by all parties. The police force is much respected and little feared. There is a bureaucracy made up of talented civil servants, its senior members generally free from corruption. The press is vocal, colourful, and still more or less free to write and say what it likes. There are several good universities, a system of primary and secondary education open to all, a cadre of teachers of impeccable training and talent. The postal system works faultlessly. The commuter railway system is the envy of the world. The environment is moderately well protected, the arts are reasonably well assisted—Hong Kong is, in short, a part of China in which any civilised human might wish to live.

It cannot escape the notice of even the most rabidly anti-colonial campaigner that the essential livable decency of the place stems not necessarily from any peculiarly innate goodness in its people, but from—may one dare to say this today?—the wisdom and benevolence of the colonial masters who planned and ruled the territory for the century and a half so lately ended.

Much the same might be said of a whole raft of former British possessions. Comparisons between the practical aspects of living in almost any one of them, and of living in countries once ruled by rival Empires, nearly always tend to favour (all chauvinism aside, though I would not blame any reader for doubting me) whichever one was once directed from London. Compare, for example, the courts in (formerly British-run) Malaysia with those in Indonesia, where the Dutch so long held sway. Post a domestically bound letter in a village outside Bombay, and compare its progress with one similarly mailed in a town near Tijuana. The railway system in Kenya (British) still works splendidly; that in Ethiopia (as Abyssinia, Italian) is dire. Papeete (French) is a tawdry Tahitian slum, Apia

(once British, as Samoa) a quiet mid-Pacific gem. And so on, and so on.