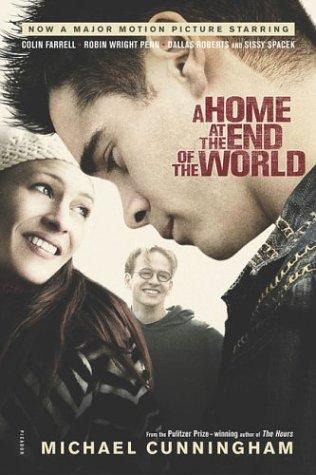

A home at the end of the world

Read A home at the end of the world Online

Authors: Michael Cunningham

Tags: #Domestic fiction, #Love Stories, #Literary, #General, #United States, #New York (State), #Gay Men, #Fiction, #Parent and child, #Triangles (Interpersonal Relations), #Fiction - General, #Male friendship, #Gay

Praise for

A Home at the End of the World

“Once in a great while, there appears a novel so spellbinding in its beauty and sensitivity that the reader devours it nearly whole, in great greedy gulps, and feels stretched sore afterwards, having been expanded and filled. Such a book is Michael Cunningham’s

A Home at the End of the World.

”

—Sherry Rosenthal,

The San Diego Tribune

“Michael Cunningham has written a novel that all but reads itself.”

—Patrick Gale,

The Washington Post Book World

“A touching contemporary story…This novel is full of precise treasures….

A Home at the End of the World

is the issue of an original talent.”

—Herbert Gold,

The Cleveland Plain Dealer

“Beautiful…This is a fine work, one of grace and great sympathy.”

—Linnea Lannon,

Detroit Free Press

“Luminous with the wonders and anxieties that make childhood mysterious…

A Home at the End of the World

is a remarkable accomplishment.”

—Laura Frost,

San Francisco Review

“Fragile and elegant…Cunningham employs all his talents, and they are considerable, to try to map out our contemporary emotional terrain.”

—Vince Passaro,

Newsday

“Brilliant and satisfying…as good as anything I’ve read in years…Hope in the midst of tragedy is a fragile thing, and Cunningham carries it with masterful care.”

—Gayle Kidder,

The San Diego Union

“Exquisitely written…lyrical…An important book.”

—

The Charleston Sunday News and Courier

Also by Michael Cunningham

Flesh and Blood

The Hours

Land’s End: A Walk in Provincetown

A HOME AT THE END OF THE WORLD

MICHAEL CUNNINGHAM

A Home at the End of the World

was started during hard times. By the date of its completion—nearly six years later—things had eased somewhat. For those more comfortable circumstances I thank the National Endowment for the Art and

The New Yorker

.

I must reserve the bulk of my gratitude, though, for several friends whose generosity literally rescued this book during its early phases, when encouragement, shelter, and even a working typewriter were sometimes hard to find. Thanks, with love, to Judith E. Turt, Donna Lee, Cristina Thorson, and Rob and Dale Cole.

Also of immeasurable help were Jonathan Galassi, Gail Hochman, Sarah Metcalf, Anne Rumesy, Avery Russell, Lore Segal, Roger Straus, the Yaddo Corporation, and, as always, my family.

A HOME AT THE END OF THE WORLD. Copyright @ 1990 by Michael Cunningham. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America., No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. For information, address Picador, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10010.

Picador® is a U.S. registered trademark and is used by Farrar, Straus and Giroux under license from Pan Books Limited.

For information on Picador Reading Group Guides, as well as ordering, please contact the Trade Marketing department at St. Martin's Press.

Phone: 1-800-221-7945 extension 763

Fax: 212-677-7456

E-mail: [email protected]

Two chapters of this book appeared in earlier form in

The New Yorker

.

Acknowledgments for permission to reprint previously published material appear on page 344

ISBN: 978-0-374-70759-0

This book is for Ken Corbett

The Poem That Took

the Place of a Mountain

There it was, word for word,

The poem that took the place of a mountain.

He breathed in its oxygen,

Even when the book lay turned in the dust of his table.

It reminded him how he had needed

A place to go to in his own direction,

How he had recomposed the pines,

Shifted the rocks and picked his way among clouds,

For the outlook that would be right,

Where he would be complete in an unexplained completion:

The exact rock where his inexactnesses

Would discover, at last, the view toward which they had edged,

Where he could lie and, gazing down at the sea,

Recognize his unique and solitary home.

—W

ALLACE

S

TEVENS

PART I

BOBBY

O

NCE

our father bought a convertible. Don’t ask me. I was five. He bought it and drove it home as casually as he’d bring a gallon of rocky road. Picture our mother’s surprise. She kept rubber bands on the doorknobs. She washed old plastic bags and hung them on the line to dry, a string of thrifty tame jellyfish floating in the sun. Imagine her scrubbing the cheese smell out of a plastic bag on its third or fourth go-round when our father pulls up in a Chevy convertible, used but nevertheless—a moving metal landscape, chrome bumpers and what looks like acres of molded silver car-flesh. He saw it parked downtown with a For Sale sign and decided to be the kind of man who buys a car on a whim. We can see as he pulls up that the manic joy has started to fade for him. The car is already an embarrassment. He cruises into the driveway with a frozen smile that matches the Chevy’s grille.

Of course the car has to go. Our mother never sets foot. My older brother Carlton and I get taken for one drive. Carlton is ecstatic. I am skeptical. If our father would buy a car on a street corner, what else might he do? Who does this make him?

He takes us to the country. Roadside stands overflow with apples. Pumpkins shed their light on farmhouse lawns. Carlton, wild with excitement, stands up on the front seat and has to be pulled back down. I help. Our father grabs Carlton’s beaded cowboy belt on one side and I on the other. I enjoy this. I feel useful, helping to pull Carlton down.

We pass a big farm. Its outbuildings are anchored on a sea of swaying wheat, its white clapboard is molten in the late, hazy light. All three of us, even Carlton, keep quiet as we pass. There is something familiar about this place. Cows graze, autumn trees cast their long shade. I tell myself we are farmers, and also somehow rich enough to drive a convertible. The world is gaudy with possibilities. When I ride in a car at night, I believe the moon is following me.

“We’re home,” I shout as we pass the farm. I don’t know what I am saying. It’s the combined effects of wind and speed on my brain. But neither Carlton nor our father questions me. We pass through a living silence. I am certain at that moment that we share the same dream. I look up to see that the moon, white and socketed in a gas-blue sky, is in fact following us. It isn’t long before Carlton is standing up again, screaming into the rush of air, and our father and I are pulling him down, back into the sanctuary of that big car.

JONATHAN

W

E GATHERED

at dusk on the darkening green. I was five. The air smelled of newly cut grass, and the sand traps were luminous. My father carried me on his shoulders. I was both pilot and captive of his enormity. My bare legs thrilled to the sandpaper of his cheeks, and I held on to his ears, great soft shells that buzzed minutely with hair.

My mother’s red lipstick and fingernails looked black in the dusk. She was pregnant, just beginning to show, and the crowd parted for her. We made our small camp on the second fairway, with two folding aluminum chairs. Multitudes had turned out for the celebration. Smoke from their portable barbecues sharpened the air. I settled myself on my father’s lap, and was given a sip of beer. My mother sat fanning herself with the Sunday funnies. Mosquitoes circled above us in the violet ether.

That Fourth of July the city of Cleveland had hired two famous Mexican brothers to set off fireworks over the municipal golf course. These brothers put on shows all over the world, at state and religious affairs. They came from deep in Mexico, where bread was baked in the shape of skulls and virgins, and fireworks were considered to be man’s highest form of artistic expression.

The show started before the first star announced itself. It began unspectacularly. The brothers were playing their audience, throwing out some easy ones: standard double and triple blossomings, spiral rockets, colored sprays that left drab orchids of colored smoke. Ordinary stuff. Then, following a pause, they began in earnest. A rocket shot straight up, pulling a thread of silver light in its wake, and at the top of its arc it bloomed purple, a blazing five-pronged lily, each petal of which burst out with a blossom of its own. The crowd cooed its appreciation. My father cupped my belly with one enormous brown hand, and asked if I was enjoying the show. I nodded. Below his throat, an outcropping of dark blond hairs struggled to escape through the collar of his madras shirt.

More of the lilies exploded, red yellow and mauve, their silver stems lingering beneath them. Then came the snakes, hissing orange fire, a dozen at a time, great lolloping curves that met, intertwined, and diverged, sizzling all the while. They were followed by huge soundless snowflakes, crystalline bodies of purest white, and those by a constellation in the shape of Miss Liberty, with blue eyes and ruby lips. Thousands gasped and applauded. I remember my father’s throat, speckled with dried blood, the stubbly skin loosely covering a huge knobbed mechanism that swallowed beer. When I whimpered at the occasional loud bang, or at a scattering of colored embers that seemed to be dropping directly onto our heads, he assured me we had nothing to fear. I could feel the rumble of his voice in my stomach and my legs. His lean arms, each lazily bisected by a single vein, held me firmly in place.

I want to talk about my father’s beauty. I know it’s not a usual subject for a man—when we talk about our fathers we are far more likely to tell tales of courage or titanic rage, even of tenderness. But I want to talk about my father’s frank, unadulterated beauty: the potent symmetry of his arms, blond and lithely muscled as if they’d been carved of raw ash; the easy, measured grace of his stride. He was a compact, physically dignified man; a dark-eyed theater owner quietly in love with the movies. My mother suffered headaches and fits of irony, but my father was always cheerful, always on his way somewhere, always certain that things would turn out all right.

When my father was away at work my mother and I were alone together. She invented indoor games for us to play, or enlisted my help in baking cookies. She disliked going out, especially in winter, because the cold gave her headaches. She was a New Orleans girl, small-boned and precise in her movements. She had married young. Sometimes she prevailed upon me to sit by the window with her, looking at the street, waiting for a moment when the frozen landscape might resolve itself into something ordinary she could trust as placidly as did the solid, rollicking Ohio mothers who piloted enormous cars loaded with groceries, babies, elderly relations. Station wagons rumbled down our street like decorated tanks celebrating victory in foreign wars.

“Jonathan,” she whispered. “Hey, boy-o. What are you thinking about?”

It was a favorite question of hers. “I don’t know,” I said.

“Tell me anything,” she said. “Tell me a story.”

I was aware of the need to speak. “Those boys are taking their sled to the river,” I told her, as two older neighborhood boys in plaid caps—boys I adored and feared—passed our house pulling a battered Flexible Flyer. “They’re going to slide it on the ice. But they have to be careful about holes. A little boy fell in and drowned.”

It wasn’t much of a story. It was the best I could manage on short notice.

“How did you know about that?” she asked.

I shrugged. I had thought I’d made it up. It was sometimes difficult to distinguish what had occurred from what might have occurred.

“Does that story scare you?” she said.

“No,” I told her. I imagined myself skimming over a vast expanse of ice, deftly avoiding the jagged holes into which other boys fell with sad, defeated little splashes.

“You’re safe here,” she said, stroking my hair. “Don’t you worry about a thing. We’re both perfectly safe and sound right here.”

I nodded, though I could hear the uncertainty in her voice. Her heavy-jawed, small-nosed face cupped the raw winter light that shot up off the icy street and ricocheted from room to room of our house, nicking the silver in the cabinet, setting the little prismed lamp abuzz.

“How about a

funny

story?” she said. “We could probably use one just about now.”

“Okay,” I said, though I knew no funny stories. Humor was a mystery to me—I could only narrate what I saw. Outside our window, Miss Heidegger, the old woman who lived next door, emerged from her house, dressed in a coat that appeared to be made of mouse pelts. She picked up a leaf of newspaper that had blown into her yard, and hobbled back inside. I knew from my parents’ private comments that Miss Heidegger was funny. She was funny in her insistence that her property be kept immaculate, and in her convictions about the Communists who operated the schools, the telephone company, and the Lutheran church. My father liked to say, in a warbling voice, “Those Communists have sent us another electric bill. Mark my words, they’re trying to force us out of our homes.” When he said something like that my mother always laughed, even at bill-paying time, when the fear was most plainly etched around her mouth and eyes.

That day, sitting by the window, I tried doing Miss Heidegger myself. In a high, quivering voice not wholly different from my actual voice I said, “Oh, those bad Communists have blown this newspaper right into my yard.” I got up and walked stiff-legged to the middle of the living room, where I picked up a copy of

Time

magazine from the coffee table and waggled it over my head.

“You Communists,” I croaked. “You stay away now. Stop trying to force us out of our homes.”

My mother laughed delightedly. “You are

wicked

,” she said.

I went to her, and she scratched my head affectionately. The light from the street brightened the gauze curtains, filled the deep blue candy dish on the side table. We were safe.

My father worked all day, came home for dinner, and went back to the theater at night. I do not to this day know what he did all those hours—as far as I can tell, the operation of a single, unprosperous movie theater does not require the owner’s presence from early morning until late at night. My father worked those hours, though, and neither my mother nor I questioned it. He was earning money, maintaining the house that protected us from the Cleveland winters. That was all we needed to know.

When my father came home for dinner, a frosty smell clung to his coat. He was big and inevitable as a tree. When he took off his coat, the fine hair on his forearms stood up electrically in the soft, warm air of the house.

My mother served the dinner she had made. My father patted her belly, which was by then round and solid as a basketball.

“Triplets,” he said. “We’re going to need a bigger house. Two bedrooms won’t do it, not by a long shot.”

“Let’s just worry about the oil bill,” she said.

“Another year,” he said. “A year from now, and we’ll be in a position to look at real estate.”

My father frequently alluded to a change in our position. If we arranged ourselves a certain way, the right things would happen. We had to be careful about how we stood, what we thought.

“We’ll see,” my mother said in a quiet tone.

He got up from the table and rubbed her shoulders. His hands covered her shoulders entirely. He could nearly have circled her neck with his thumb and middle finger.

“You just concentrate on the kid,” he said. “Just keep yourself healthy. I’ll take care of the rest.”

My mother submitted to his caresses, but took no pleasure in them. I could see it on her face. When my father was home she wore the same cautious look she brought to our surveys of the street. His presence made her nervous, as if some part of the outside had forced its way in.

My father waited for her to speak, to carry us along in the continuing conversation of our family life. She sat silent at the table, her shoulders tense under his ministrations.

“Well, I guess it’s time for me to get back to work,” he said at length. “So long, sport. Take care of the house.”

“Okay,” I said. He patted my back, and kissed me roughly on the cheek. My mother got up and started to wash the dishes. I sat watching my father as he hid his muscled arms in his coat sleeves and returned to the outside.

Later that night, after I’d been put to bed, while my mother sat downstairs watching television, I snuck into her room and tried her lipstick on my own lips. Even in the dark, I could tell that the effect was more clownish than alluring. Still, it revised my appearance. I made red spots on my cheeks with her rouge, and penciled black brows over my own pale blond ones.

I walked light-footed into the bathroom. Laughter and tinkling music drifted up through the stairwell. I put the bathroom stool in the place where my father stood shaving in the mornings, and got up on it so I could see myself in the mirror. The lips I had drawn were huge and shapeless, the spots of crimson rouge off-center. I was not beautiful, but I believed I had the possibility of beauty in me. I would have to be careful about how I stood, what I thought. Slowly, mindful of the creaky hinge, I opened the medicine cabinet and took out my father’s striped can of Barbasol. I knew just what to do: shake the can with an impatient snapping motion, spray a mound of white lather onto my left palm, and apply it incautiously, in profligate smears, to my jaw and neck. Applying makeup required all the deliberation one might bring to defusing a bomb; shaving was a hasty and imprecise act that produced scarlet pinpoints of blood and left little gobbets of hair—dead as snakeskin—behind in the sink.

When I had lathered my face I looked long into the mirror, considering the effect. My blackened eyes glittered like spiders above the lush white froth. I was not ladylike, nor was I manly. I was something else altogether. There were so many different ways to be a beauty.

My mother grew bigger and bigger. On a shopping trip I demanded and got a pink vinyl baby doll with thin magenta lips and cobalt eyes that closed, when the doll was laid flat, with the definitive click of miniature window frames. I suspect my parents discussed the doll. I suspect they decided it would help me cope with my feelings of exclusion. My mother taught me how to diaper it, and to bathe it in the kitchen sink. Even my father professed interest in the doll’s well-being. “How’s the kid?” he asked one evening just before dinner, as I lifted it stiff-limbed from its bath.

“Okay,” I said. Water leaked out of its joints. Its sulfur-colored hair, which sprouted from a grid of holes punched into its scalp, had taken on the smell of a wet sweater.

“Good baby,” my father said, and patted its firm rubber cheek with one big finger. I was thrilled. He loved the baby so.

“Yes,” I said, holding the lifeless thing in a thick white towel.

My father hunkered down on his huge hams, expelling a breeze spiced with his scent. “Jonathan?” he said.

“Uh-huh.”

“You know boys don’t usually play with dolls, don’t you?”

“Well. Yes.”

“This is your baby,” he said, “and that’s fine for here at home. But if you show it to other boys they may not understand. So you’d better just play with it here. All right?”

“Okay.”

“Good.” He patted my arm. “Okay? Only play with it in the house, right?”

“Okay,” I answered. Standing small before him, holding the swaddled doll, I felt my first true humiliation. I recognized a deep inadequacy in myself, a foolishness. Of course I knew the baby was just a toy, and a slightly embarrassing one. A wrongful toy. How had I let myself drift into believing otherwise?

“Are you all right?” he asked.

“Uh-huh.”

“Good. Listen, I’ve got to go. You take care of the house.”

“Daddy?”

“Yeah?”

“Mommy doesn’t want to have a baby,” I said.

“Sure she does.”

“No. She told me.”

“Jonathan, honey, Mommy and Daddy are both very happy about the baby. Aren’t you happy, too?”

“Mommy hates having this baby,” I said. “She told me. She said you want to have it, but she doesn’t want to.”

I looked into his gigantic face, and could see that I had made some sort of contact. His eyes brightened, and the delta of capillaries that spread over his nose and cheeks stood out in sharper, redder relief against his pale skin.

“It’s not true, sport,” he said. “Mommy sometimes says things she doesn’t mean. Believe me, she’s as happy about having the baby as you and I are.”

I said nothing.

“Hey, I’m late,” he said. “Trust me. You’ll have a little sister or brother, and we’re all going to be crazy about her. Or him. You’ll be a big brother. Everything’ll be great.”

After a moment he added, “Take care of things while I’m gone, okay?” He stroked my cheek with one spatulate thumb, and left.