Out of Bounds (10 page)

Authors: Beverley Naidoo

OUT OF BOUNDS

A Q&A with Beverley Naidoo

My Banned Book

An Excerpt from Beverley’s Novel

Burn My Heart

You write mostly novels. What inspired you to make a collection of short stories?

Short stories are a challenge to write because they have to be so compact. I once heard Nadine Gordimer, the South African Nobel Laureate, say that the short story has to be like an egg. Every part has to connect to every other part. “The Dare,” “The Typewriter,” “The Gun,” and “The Playground” were originally published in different collections in the United Kingdom. It occurred to me that each was set in a different decade in South Africa and that the characters and their stories said something about “being at that point in time.” If each set of characters could step in front of a mirror, the wider picture behind them would reflect the changing history. All I had to do was fill in the gaps and I would have a collection of seven stories set in seven decades. So, in 2000, I decided to write stories for the 1950s, 1960s, and the year 2000.

Did writing stories that had to be set in particular decades change the writing process?

I started by considering what were really important events before I began to think about my characters. The classification of everyone in the country into one of four so-called “racial groups” was something

terrible and fundamental in the 1950s. That led me to think about a child who experiences the shock of discovering what classification means to him and his family. For the 1960s, I knew that my story had to involve the massacre at Sharpeville because that changed the course of history in South Africa. I decided to explore what the event might mean to a white child whose background was different from mine and that of most other white children. Lily’s parents completely reject apartheid. They are brave and teach Lily important values of equality, justice, and respect. But this means that Lily finds herself the odd one out in her whites-only school. Like every child, Lily wants friendship, and her inner conflict gives a strong dynamic that leads into the bigger story.

How did you create a story for the year 2000 when the decade was only beginning?

I thought about the millennium and how we were moving from one century to another. Extraordinary floods hit the East African coast as the new century began, and I recalled the amazing image on television of a Mozambican mother who gave birth to her baby in a tree. It was such a symbol of resilience, courage, and hope in the midst of disaster. Already by 2000, people were saying that our world has become so unstable that the twenty-first century will be the “century of refugees.” I also wanted to

explore the vast, dangerous divide between the “haves” and “have nots.” The divide lives on after the ending of apartheid and is also global. That led me to think about Rohan in his comfortable house at the top of the hill and Solani in his rickety, fragile home on the slope below. I called the story “Out of Bounds” because each boy crosses a boundary. It is not just a physical boundary, but each takes a vital step forward in crossing boundaries of the mind and, I believe, of the heart.

Are any of the stories based on you or your personal experiences?

Like other fiction writers, I often delve deep into myself and my imagination as I try to make sense of things that have intrigued, puzzled, or troubled me. Nicky’s parents in “The Dare” take her to a guest farm under a mountain in the Magaliesberg, which is where my parents used to take my brother and me. We were “townies,” and I remember wanting to be accepted by the family of white children who lived on the farm and who were a lot tougher than I was. There are details from real life in the story, including the one-legged chameleon and the doll Margaret, which I still have! However, the events that take place are fiction, although, at a deep level, I was exploring the idea of how easily we become implicated in an immoral system.

Most of the stories contain things remembered

and transformed. In “One Day, Lily, One Day,” Lily’s teachers run in panic to shut the school gates because of a false rumor. That happened in my school for white girls on March 21, 1960, the day of the Sharpeville massacre. In “The Typewriter,” Khulu bravely tries to hide the typewriter in one of the garages like those at the back of the apartment block where I grew up. The idea of a story about a typewriter used for resistance work came from the typewriter that my brother hid behind the kitchen cupboard in the apartment that I rented after leaving home. Very fortunately, the security police who raided my apartment never found it.

You have adapted “The Playground” into a stage play. What was that like?

I transformed rather than adapted it! I had to pull apart my very compact short story and dig up every tension within it. I added a third act so I could explore Rosa and Hennie when they were sixteen. I learned much more about my characters, especially through workshops with actors and my director, Olusola Oyeleye. We went out to South Africa as part of the research and development process. I wove traditional songs throughout my script, as music is part of life in South Africa and conveys emotion so powerfully.

The Playground

premiered at the Polka Theatre in London in 2004 and was a

Time Out

Critics’ Choice Pick of the Year.

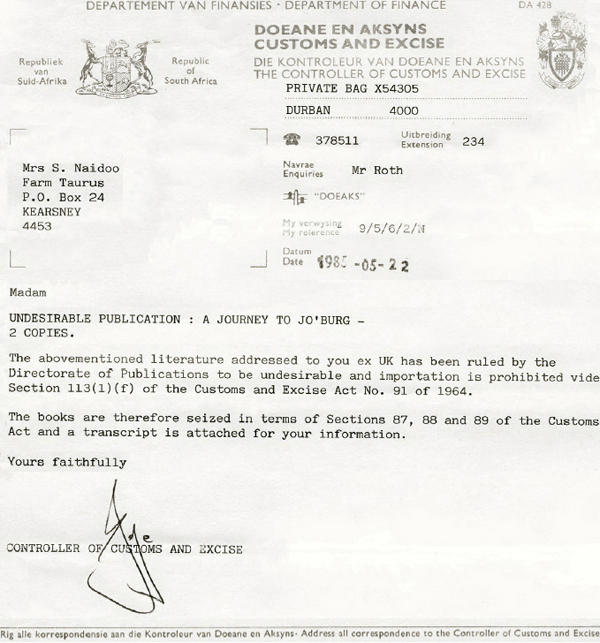

My first children’s book,

Journey to Jo’burg

, was published in the UK in March 1985. I sent two copies to South Africa for my nephews and nieces but the books never arrived. Instead, my sister-in-law received a nasty letter telling her that

Journey to Jo’burg

had been banned and “seized.” The apartheid government had stolen my books! They banned the book as soon as they realized that half its royalties were going to a forbidden organization, the British Defense and Aid Fund for Southern Africa. This fund helped political prisoners and their families—people like Nelson Mandela and so many others who struggled against apartheid and whose families were left without breadwinners. But I was surprised at how quickly the authorities had outlawed

Journey to Jo’burg.

I was also angry and upset. How ridiculous that they would threaten to arrest someone for wanting to read a story!

I wrote “They Tried to Lock Up Freedom” nearly twenty years later, after the course of history was changed in my birth country. But my poem is not just about South Africa. Wherever we are faced with bullies and violence, it is about the truth in the old saying “The pen is mightier than the sword.” Or, as a ten year old once told me, “The sword has no imagination. It can only kill. The pen has imagination.”

They seized the book

Ripped out its spine

Flung it in the fire

Pages fluttered through smoke

They grabbed the pages

Scratched out lines

Crushed them in their fists

Words squeezed through knuckles

They twisted the words

Tore out sound

Swallowed them in their silence

The heart of the book cried out

The pages grew wings

The words breathed Freedom

Beverley Naidoo

© Beverley Naidoo 2004. Commissioned by Barbican Education.

Burn My Heart

A STORM OUTSIDE

Mathew curled up under his crisp cotton sheet, listening to the rain drumming on the tin roof. It was a stroke of luck. By the time Father inspected around the fence in the morning light, his and Mugo’s tracks on the other side would be washed away. Father need never know of their expedition. Usually the sound of rain on the tin induced Mathew into sleep. He enjoyed feeling wrapped up securely from the elements outside. But after the telephone call from Major Smithers, he didn’t feel safe at all.

He was used to hearing grown-ups talk about the Mau Mau, especially at the club. But whenever he asked where an incident had happened, he was told “

Fortunately, not here

.” It had always been somewhere else…like Nairobi, which they seldom visited, or Naivasha or some other place in the Rift Valley on the other side of the Aberdare Mountains.

Tonight, however, Mathew lay in bed imagining that people might actually be prowling around their farm. What a fool he had been! What if the fence had been cut by a Mau Mau gang and they had met them in the bush? That would have been even more terrifying than their encounter with One-Tusk…and Mugo wouldn’t have been able to protect him, a white settler boy.

The rain beat down harder now, rattling the roof, as thunder rumbled in the distance. When Mathew was younger, he had often run into the stables to get out of a thunderstorm. He and Kamau would watch the heavens open, drenching the garden and the bush beyond. In Kamau’s stories, Ngai the Creator rolled out thunder from the top of his mountain when he was angered. There was one story in which Elephant helped Hare to cross a river. Hare offered to hold Elephant’s jar of honey while sitting on his back. By the time they reached the other side, the jar was empty. Hare was laughing but Elephant was furious at Hare’s deceit and vowed revenge. Mathew could hear Kamau ending the story as if he had made it specially for him, the little master: “

You see, bwana kidogo, one day Ngai will help Elephant. That day Hare

will be very sorry. Bwana kidogo, you must know that Ngai sees everything.

” Mathew coiled in his head like a snail as he remembered how it had felt to be at the mercy of One-Tusk and his anger. As the lightning cracked, splitting the night sky, he pulled his pillow over his head.

Mugo woke in the middle of the night. The first thing he heard was rain rushing to the earth. He urgently needed to pee but waited to let his eyes adjust to the gloom so he wouldn’t trip over his brother and sister sleeping on the floor beside him. As he tiptoed across the room, a drop of water splashed his forehead. The thatch was leaking again. He had helped Baba patch it up in the last rainy season. He skirted past the bed where Baba was snoring. His father slept lightly and Mugo hoped the rain would cover the sound of him tugging the metal bolt on the door. Then he opened the creaking wood just enough to squeeze out. He eased it shut behind him.

Sheets of water pitched down from the edge of the thatch. The rain was driving a stream across the compound and he decided against trying to reach the toilet area. Instead, hugging the wall, he hurried to the back of the house to relieve himself there. He took his time, enjoying the freshness of

the air and the damp earth. The rain was a blessing. With luck it would help everyone forget the incident of the fence.

He was feeling his way back when he realized that he was not alone in the compound. He pressed his back against the wall, his heart thumping. Three shadows were slicing through the torrential rain, aiming for the room where his parents were sleeping. They were almost close enough to touch with a long stick! The one in front was bent double, carrying something. A gun? The door was unbolted and they could go straight in! There was no chance of Mugo getting back inside in time to lock it.

His instinct told him to hide. Could he conceal himself between the maize stalks in the shamba? But he needed to know what was happening. Diving through the rain, he reached the entrance to the shamba and, trembling, felt his way along its thorny hedge until he thought he was in line with the front of the house. He scratched his fingers trying to feel for an opening through which he could peer. The downpour was easing slightly and he could just make out a shape standing outside like a guard. Then Baba’s and Mami’s shapes came stumbling through the door. They were probably

still half asleep. There was no screaming or shouting but Mami huddled close to his father. Where were his little brother and sister? Had his parents been forced out of bed so quietly that the little ones were still sleeping?

More shadows emerged and there was talking. Mugo strained to hear. One of the strangers was much shorter than the others and his high-pitched voice carried through the rain.

“Where is the kitchen toto?”

“…not here…sometimes he sleeps there…kitchen…Mzungu keeps him late…” Baba’s bass voice was more difficult to follow but Mugo also saw him wave his arm towards the bwana’s house.

“If you lie, you will pay.” The words flew sharp as arrows.

Mugo’s mouth felt dry. How did these young men know about him? If they had an informant, they would soon know Baba was lying. He had only once slept in the shed by the kitchen.

“Why should I lie?” Baba sounded composed. “Are we not coming with you without trouble?”

“Must I look, captain?” The shape of the guard stepped away from the door.

“Hapana. No, we go.” It was the same rapid, higher voice that had asked about the kitchen toto. He was the one with the gun and clearly the leader. Mugo was surprised how short he was, probably not much taller than himself. Mugo made out a peaked cap but could see nothing of the face underneath.

With Mami and Baba between them, the young men headed briskly toward the row of banana trees that separated Mugo’s compound from Mzee Josiah’s. Mugo was torn. Shouldn’t he go back to his brother and sister? That’s what his parents would want him to do. But he also had to know where the strangers were taking them! He would lose them in the rain-filled night if he didn’t follow instantly.

The shamba extended almost to the banana trees but the thorn hedge was so thickly planted that it would be difficult to get out at that end. He was obliged to hurry back to the shamba’s entrance and, by the time he was running softly on the other side, he had lost the figures in the thick wet darkness. Mugo imagined, however, that they might be heading for Mzee Josiah’s door. In daylight you could see it from the banana trees, but as he emerged through the web of dripping leaves, he realized he would have to sneak up closer to see anything.

Mzee Josiah and his wife lived on their own. Their children were all grown up, working in Nairobi and Nyeri as clerks and teachers, for more money than their parents could ever earn. Halfway between the banana trees and the house was a fat mango tree. Mzee Josiah claimed his mangoes were juicier than any in the memsahib’s orchard and that his cook’s nose could sniff out any young thieves. When ripe, the sweet golden finger-licking smell of the fruit was a great temptation. Occasionally, made bold by friends, Mugo risked capturing a couple of mangoes. With his blood pulsing just as strongly now, he trod softly toward the tree. Tonight the rain was his friend, covering his sounds! But as he slid between the mesh of mango branches and leaves, he felt a thousand fingers circling his neck. Seconds later, he heard a shout, a scream, then scuffling and muffled shrieks. Even the gun hadn’t made Mzee Josiah and Mama Mercy come as quietly as Baba and Mami.

“Stop their mouths!” It was the captain again. “Haraka! Hurry! These ones will make us late!”

Late for what? No one said it, but it was understood. Mugo’s hammering heart knew…just as it knew why they had asked for him too.